Consumptions of Blackness in Academic Spaces

October 2, 2018

With an increasingly diversifying curriculum in school districts across the country, black and brown authors are appearing on more class reading lists than ever before — James Baldwin, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Maya Angelou, and Zora Neale Hurston being some of the most frequent appearances.

Black and brown authors being included in the classroom allows for students to consider topics from a diverse range of perspectives, giving them deeper insight into history and global politics. However, it is even in the most progressive of classrooms, the identity politics of the colonizer and the colonized find themselves at play.

America has long had a history of consuming blackness. From slave labor providing America with the necessary funds to become a global superpower, to the systematic incarceration of black subjects to provide physical labor, there has never been a time nor space within the last four hundred years that the black identity has not been available for consumption. Education has not been unique in this instance. There have been four distinct movements in the consumption of blackness in the American academic system.

In the first movement, the academy demanded physical labor in the form of slavery, making the strength of black subjects necessary to establish the physical universities themselves.

Second, the academy began to appropriate black authorship and knowledge production to create some of the most iconic fields of study in the modern educational system. This can be seen in the appropriation of the work of W.E.B Du Bois by his white people.

Third, white Scholars prey upon blackness as a way to not only to conceive of new subjects to be studied, but also to fulfill the negrophilia, or lust for looking onto blackness, that has seeped into the fabric of the American education system.

As classroom curricula diversify and seek out more black authorship, a fourth form of consumption emerges. Black authors, artists, intellectuals and academics alike find themselves being used as a looking glass for white audiences, allowing for liberal white America to engage blackness as on paper as opposed to living and interacting with black people in person, giving white people the gratification of engaging in a ‘good’ action without engaging in ‘good’ work.

It is within the gaze of the colonizer, that the colonized subject finds itself as the researcher and the researched. The spectator and the spectated:he black. It is in these stages of consumption that the colonizer, colonized identities find themselves in a place of entanglement. Two separate balls of yarn twisted into the American classroom. Holding one end of the ontological ribbon is the colonized student is entrapped within the larger historical context of the colonized subject, in American history. On the other side is the teacher embodying the symbolic order of the colonizer. Each holding their end of the twisted rope is the epistemic origin of any classroom interaction. It is only after we begin the process of detangeling that we may begin to read.

***

Black production for and within the system of American education begins with the origins of formal education in the nation. There is no better place to see this than in the American University. Harvard, America’s first institution of higher learning, had slaves tend to the needs of students and faculty. Yale University used funds gained by its own slave plantation to fund it graduate school program. The University of Virginia was literally built by slaves. Georgetown University paid for its construction by way of a tobacco plantation holding over 200 slaves. Georgetown paid for scholarships via funds gained from the plantation and the founders of Georgetown were some of the largest slave owners in Maryland at the time of its inception. These examples show how blackness was physically necessary to construct the American University as we know it today.

The consumption of blackness did not end with the abolition of slavery, instead it manifested itself into the utilization of the black identity through the larger structure of the American education system. One of the best example of this finds itself in the history of sociology. W.E.B Du Bois introduced a unique method of empirical analysis, and scientific methods revolutionizing modern sociology, however Du Bois’ contributions are often credited to his white contemporaries. These methods laid the groundwork for some the most lucrative field of study for American universities while failing to credit the black originator of the ideas.

Black people have been used as a means of advancing research in many early manifestations of study. The infamous ‘Tuskegee Experiments’ in which numerous black subjects were unknowingly injected with syphilis, is one of the most well-known instances; however, it is within a long history of black people being used in this way. The life of Henrietta Lack was another well known instance in which a black woman’s cells were used for medical testing without the knowledge or consent of her or her family. Moreover, some of the original contraceptive methods were developed on slave women in the 19th century. It is within these instances that we see the way blackness is treated as a means to an end, an opportunity to be capitalized on. These developments on the backs of black subjects are directly responsible for the advancement of these lucrative fields of medicine and biological research within formal academia.

Consumptions of blackness extends beyond physical labor and torment, blackness as a semiotic signifier is reduced to a spectacularity. One of the most influential intellectuals in the mid-twentieth century was a man by the name of Daniel Patrick Moynihan. Moynahan was hired in the Department of Labor under the Kennedy administration staying there under the administration of Lyndon B. Johnson as well. It was Johnson’s so called “War on Poverty” that shifted Moynahan’s focus to the correlation of family structure and economics.

This and the Civil Rights Movement of the mid 1960s sparked Moynahan’s interest the dynamics of black American families. The product of this came in the spring of 1965 with a report written by Monahan and his team. Moynahan, a white man, wrote the report as an analysis of black families after the civil rights movement. “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action” better known as “The Moynihan Report” skyrocketed the career of its author, granting him a job under four U.S president, a four term senate position and a professor position at Harvard.

The Moynihan Report functioned as a colonist’s introspective into black life constructed perfectly for white consumption in academic and federal institutions alike. The Atlantic’s Daniel Geary provided an annotated version of the report in 2015 and said this regarding the political reaction as a result of the Moynahn’s work:

“Many liberals understood the report to advocate new policies to alleviate race-based economic inequalities. But conservatives found in the report a convenient rationalization for inequality; they argued that only racial self-help could produce the necessary changes in family structure. Some even used the report to reinforce racial stereotypes about loose family morality among African Americans.”

From either side of the political spectrum, whiteness, particularly individuals who were employed as academics, political pundits, journalists, etc. Found way to consume blackness. In the fifty years since the report’s debut, it is still one of the most provocative pieces of writing concerning scenes of blackness in the modern era. This report, and others like it, have been subject to great academic activity in recent years, utilizing the spectacle of blackness as a means of spectacle. This is an example of black consumption in the academy because it is black life that is necessary for these conversations.

It is during the out of session months that high-school English departments around the country find themselves editing and revising their required reading lists and curriculum for students. It has been in the past ten to fifteen years that there has been an even more specific focus on the types of books selected for the newer edition of student material.

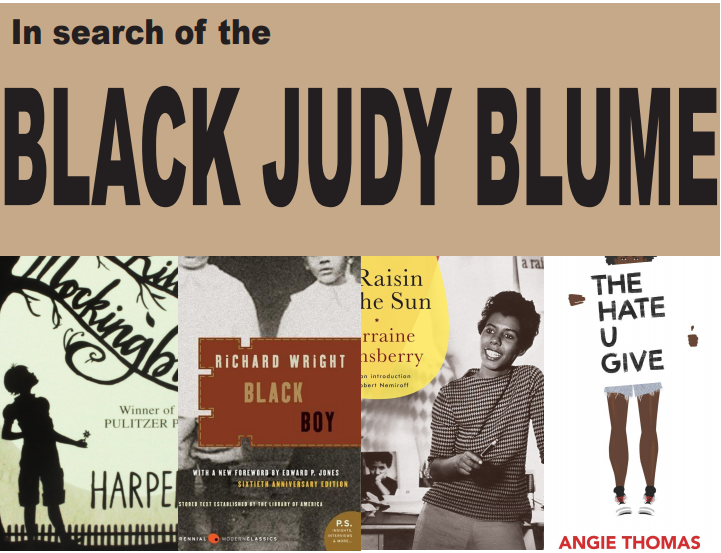

Specifically ‘classic’ American literature finds itself under scrutiny for the use of racial epithets by white characters as well as other overt instances of white supremacy. Texts such as Huckleberry Finn and To Kill a Mockingbird find themselves replaced with A Raisin in the Sun and even more recently The Hate U Give. However, even in the later of the texts consumption of blackness becomes ever present. blackness is no longer the source of physical labor, or intellectual theft, but rather becomes an object.

It is as the white gaze is put upon blackness that the black subject then finds itself in a state of objectification. It is in this state of spectacle that the black author, and the characters created by the black author, then become physical tools used to teach white children about modern racism and white supremacy.

It was in eighth grade when I found myself sitting in a classroom full of sobbing white children while the teacher presented a slide show of images detailing the violences that were endured by Jim Crow era blacks in the American South. However, within this display of emotion, the black subject was then utilized as a teaching mechanism.

This same phenomenon is seen among white students’ reactions to countless other texts. Take the battered face of Emmett Till, or the the lynching photos presented to students in American history courses. It is the suffering of the black subject used to show white students the reality of black life. It is not necessary to show these same images to black students. The bloody history of black American life is not lost upon them. It is these instances of the black spectacle that is utilized as a demonstration for the white student. This is seen in fiction writing as well. Some of the titles frequenting best, young adult include, Christopher Paul-Curtis’s The Watsons Go to Burmingham, The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas, The Skin I’m in by Sharon G. Flake. All these books have the same thing in common; some aspect of the story is surrounding the larger spectacle of the suffering of a black character. That is what is required in order to have a timeless children’s classic written by a black author. A black character must be subject to gratuitous violence in order for white readers to engage with it. There is no black Judy Blume. Nor is there a black Beverly Clearly.

*A shorter version of this article was published in the Sept. 28 issue of The Evanstonian.