Colonial Algebra

November 12, 2018

*Content warning: This article talks in-depth about genocide, homocide, sexual violence and suicide. Please read at your own discretion.

The business of transforming a human being into an object is a particularly pernicious one. It is also one that is not foreign to us here in the United States. It is the business that has allowed us to develop our notions of self, subjectivity and autonomy through not only an establishment of colonial law, but an establishment of colonial bodies. By creating an outline of which subjects fit into a postcolonial society, the task of the colonizers only becomes ‘how do I turn an uncolonized subject into a colonized one.’ Once colonial rule has been established, it then begins the process of transforming an uncolonized subject into a colonized one.

These scenes of making, unmaking, and engenderment become the event horizons that establish our means of acquiring knowledge. Essentially, when subjects are put through a colonial rule, they become a different version of themselves that alters their fundamental being in the universe. It is from these horizons, that we may conceptualize our notions of time, the human and the object. As we progress from here, we allow these premises to the structure our conceptualizations of the slave, slave masters, criminal, victim. Before we can explore the latter, we must first explore the instances in which this transformation can occur, and what exactly is left after this process.

In order to engage in the exploration, we must first establish our grammar. It is crucial that we understand time, Blackness untimely relationship to time itself. Calvin Warren, a professor of philosophy at Emory University, provided the most comprehensive definition of an event horizon that will allow us to conceptualize time in this application.

The event horizon is that which exceeds metaphysical epistemes and incorrigibly escapes the clutches of metaphysics, even as metaphysics attempts to capture it through objectification.

Simply put, colonial time asks us to see all events through time as having a beginning, middle and end. That we are somehow in a distinct moment in time known as the ‘present’ that is separate from the ‘past’ because events from the ‘past’ have ended, and events in the ‘present’ are still occurring. However, time as conceptualized by Calvin Warren and other Black scholars views time as being more abstract and fractured. Blackness and its movement through time often lacks a consistent reliable form of subjectivity to view Black life through the lenses of colonial times.

Slavery, and more specifically the Middle Passage, is one of these event horizons that break the barriers of the past, present and future and exists beyond time. All of the ‘historical’ examples mentioned in this article must be imagined as event horizons, as it these instances that structure not only the world, but the timescape that we live in as well.

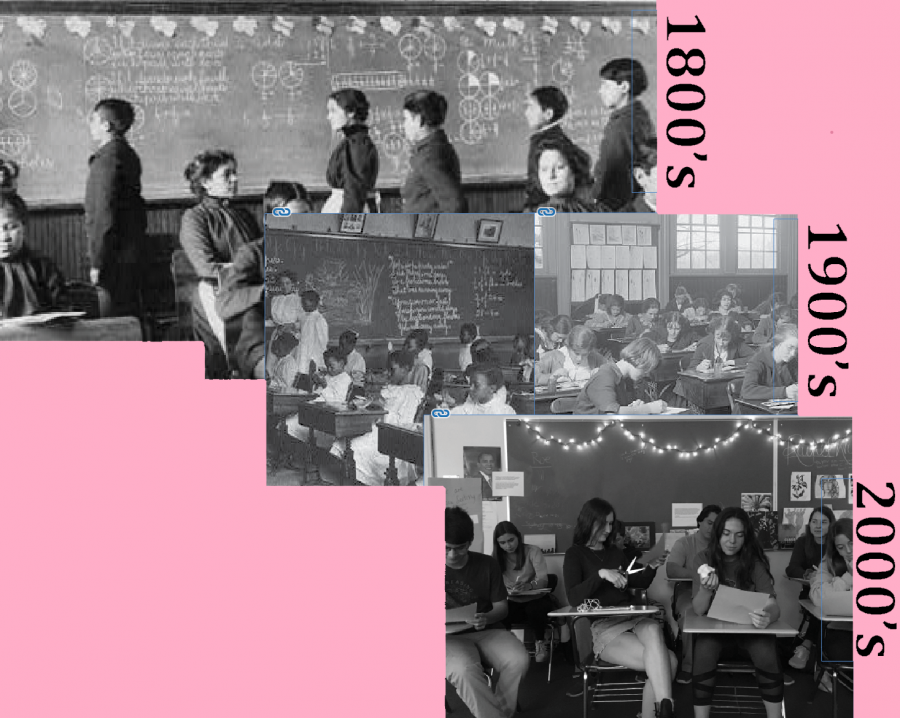

Our first example of this colonial input/output operation comes in the form of boarding schools from indigenous Americans. Beginning in the late 1800s and ending roughly in the 1970s, children from indigenous communities were kidnapped from their homes and forced to attend ‘schools’ in the East and West coast. These schools were predicated on the notion of assimilation for indigenous students forcing them to adapt to colonial norms. Notions of gender binaries, nuclear families, ridgid sexual orientations, eating habits and other euro-centric cultural norms were forced upon students. In addition to this, students were given white names that they went by while on campus. Students were physically forced to give up their native languages under the threat of physical violence. In addition to this, it is at these schools that we see the popularization of historical events such as Columbus Day, Thanksgiving and George Washington’s birthday, gaining recognition as a means of emphasizing the colonial narrative central to this process. Murder and sexual asault were high in these instituions as well. In a report done by Canadian Judge and politician, Murray Sinclare, the mortality rate of students was on average anywhere between 24-42 percent. Reports of heads being bashed against walls, children being thrown down stairs, drowning, shaking and burning were commonly reported from students, often falling on deaf administrative ears. More than 20,000 former attendees of these schools have submitted court claims against the shoulder and this figure fails to represent the students who were unable to possess the resources to advance court proceeding and the ones who died as a result of the abuse.

This violence was a tool, not only to break the spirit of native people, but to allow for an ontological reconfiguration. This ontological reconfiguration is the forced social and societal norms, upon them. Monogamy, gender binaries, nuclear families, forks, knives were all part of the process to eliminate any native American culture from the face of the earth. This is one example of many that indigenous subjects were put through, taking the uncolonized inglorious subject and transformed it into one that could be understood, made, unmade, dominated and controlled.

Similar relationships can be seen across Black peoples in both African and the western world. The Middle Passage is one of the first large scale instances of domination, manipulation and control of Black subjects in the colonized world. Once upon American soil, Blackness finds itself at the intersection between living and dead, a state of being absent to the restrictions of time, space and history. To get us to this place of Blackness, one must first go through the process of the Middle Passage, the first large-scale instance of our colonial equation.

Saidiya Hartman’s phenomenal book titled Lose Your Mother details the effect that the African slave trade has had on the communities of Gold Coast in West Africa. One of the most interesting aspects of the book is the relationship that Hartman has, as a Black woman, to the people of Ghana, the country in which the book takes place. To the native Ghanaian, she is seen as an outsider, someone with an origin foreign to their own—someone who is unrecognisable and not able to be understood. It is likely that those who see her as so different from themselves could have shared a common ancestor with Hartman, both living on opposite sides of the slave trade coin.

The process that made the African subject into an unknowable compilation of flesh and bone was the Middle Passage. The African subject goes in; the object comes out. It is this process that the physical body of the Black subject is stripped of the person controlling it and merely becomes the physical compilation of cells, blood and bone. This process of transformation continued through slavery in which a young slave, or Black person in modern America, often had to undergo a childhood filled with a rather peculiar period of self-discovery. Frantz Fannon so well articulated this as knowing one’s self as “an object in the midsts of other.” While the specifics may have varied from person to person, all slave children were forced through instances in their lives that produced their understanding of this ontological rapture put upon them. It was these instances within slavery and the Middle Passage that took the unmarked, uncolonized African subject and transformed it into one that could be understood, made, unmade, dominated and controlled.

The act of putting a colonial system upon a subject is replicated in practices and modern western education. It is in formal schooling that young children are first introduced to some of the restrictive notions that define our society. Gender, discipline, hegemonic power all become present in the classroom and the process of taking unmarked subjects, putting them through the schooling system, and receiving a subject ready to act within the colonized world. This replicates the process that we have seen in the past.

Take discipline, for example. When students act outside of colonial norms, they are often put through a series of programs and interventions in an attempt to conform them to a system. This process of conformity disproportionately affects students of color because it is the system’s purpose to erase and unmake the non-white student and replace them with aversion of themselves that can be received, understood and controlled by white society.

Black students have three times the suspension rate of white students at ETHS, according to figures provided by the district, even though white students make up a larger percentage of the student body. This is evidence of the fact that white students are able to fit more easily into the mold of the ‘model subject’ because it was designed around them. The intentions of whiteness behind actions of discipline is to convert the Black subject into one that can be interpreted by a white one. This is impossible. This fact reflects itself in the American prison population, specifically the school-to-prison pipeline. Students who are unable to be fully converted, dominated into a subject deemed worthy of operating within society by whiteness, find themselves forced into the prison industrial complex. Those unable to be dominated within, find themselves trapped inside for the rest of their corporeal lives.

Corporal domination is one of the facts of Black life that has become so normalized within society that it becomes almost unrecognizable. White life and self identity become predicated on the single goal to juxtapose ourselves from the subjects who aren’t able then be controlled by the colonial system. Upon this recognition, it becomes the goal of white progressives to restructure identities and notions of self in a way that can somehow be seen as independent of a colonial means of self knowledge, but still allows us to feel like a distinct and individual person. However, it is as we try to rebuild our identity that we become entangled in the same structures that one has been attempting to escape from the beginning. Blackness, on the other hand, has no access to a means of symbolic reconfiguration as its existence exists between someplace and no place that resists a colonial pinning down.