Feature shifts mindset, changes philosophy

December 26, 2018

Who am I

I have written for the feature section for the past four years — beginning my freshman year. During the majority of which, I enjoyed the capitalist ideologies reflected in the traditional journalism that reaffirmed my whiteness. I developed ambition, ignited every time I watched movies about white journalists like Spotlight and The Post, at the expense of the lived experiences of “my sources.” My stories weren’t about the people or “issues” I was covering, but rather, seeing my own name in print.

However, at the end of my junior year, I developed a new lens to examine journalism. I began writing a story rooted in the trauma and strength of my peers. Students entrusted me with their lived experiences, after continuously being dismissed — even by my own publication. They took the time to work with me so that their narratives were in ordinance with Student Privacy Law.

After all those hours of revisiting their experiences time and time again, I brought the piece to the editorial board to discuss. After taking a moment to read the piece, one person said “isn’t including these both beating a dead horse?” and another said “This is boring.”

The idea that someone would equate an individual’s lived experience surrounding trauma and their experience following said trauma, with the word “boring” and believed it to be redundant, demonstrated — to me — a lack of acknowledging those people’s humanity and emotions. At first, I attributed that to the individuals who made the comment — believing that they just weren’t empathetic.

Then, I analyzed the space further. After reacting emotionally to their comments, from my understand those in the space at large didn’t perceive their comment as “that bad.” From there, I realized that it was something about The Evanstonian and journalism that fostered a dissociation between and commodification of people’s humanity and their language.

The questions I was taught to ask myself was never “How do I handle another human’s narrative?” but rather “How does this help us win contests?” and “How does this make our paper more eye-catching — increase its value?”

The Journalistic Process

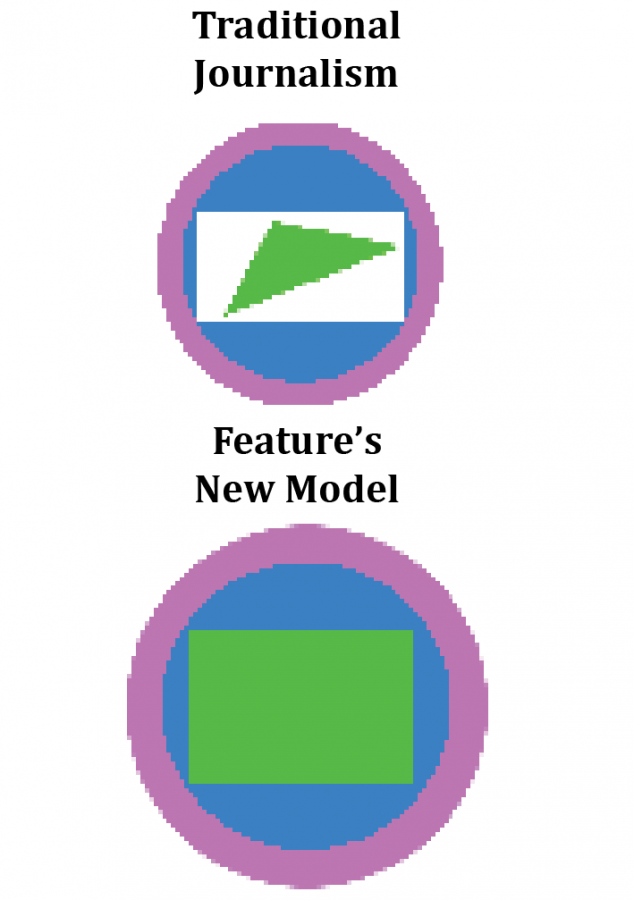

Take the model to the side — representative of my perception of traditional journalism and what feature section is attempting to move to. Beginning with traditional journalism, the purple circle represents the facts available about a given topic. The blue circle represents the writer’s knowledge about said topic — collected through research and interviews.

The white rectangle serves as a visualization for how I can construct my understanding of a topic. I can either interpret new information that assimilates into my understanding of reality [thereby disregarding some facts] or allow this new information to change my understanding of reality for a given topic.

Traditional journalism requires me to develop an angle and write the story accordingly: depicted by the green triangle. An angle is a lens through which a writer filters facts in order to focus a reader’s perspective on an issue.

Take, for example, the 16-story tower on Sherman Ave proposed last year. One could cover:

- The construction of the physical building

- The history of existing businesses

- The push back against the building

- The effects of gentrification on Evanston’s working, lower-class

Critique of our Definition of Truth – Epistemology

When examining the traditional journalistic process, I began with critically thinking about what we define as truth — visualized as the two circles in the model. Mainstream journalism reinforces the notion of a singular truth as well as the notion of truth as existing as unbiased.

The prioritization of objectivity places us, the writers, above human emotions — the deification of reporters. As a result, I have developed feelings of egotism: manifesting itself in an entitlement to the narratives of people around me. Such entitlement fractures the relationship not only with the “sources” and myself but also readers and myself and the piece and myself.

Additionally, the belief that objectivity yields truth also belittles lived experiences. We as journalists dictate that subjective narratives = bias = opinion. Yet, we simultaneously neglect and dismiss the subjectivity that exists in the process of confirming truths and in the creation of the process of confirmation itself.

This kind of splitting [black-and-white thinking] is the manifestation, causation and perpetuation of eurocentric masculinist epistemology [white men’s understanding of truth]. Sociologist and author of Black Feminist Thought, Patricia Hill Collins states,”no one group possesses the theory or methodology that allows it to discover the absolute ‘truth,’ or worse yet, proclaim its theories and methodologies as the universal norm evaluating other group’s experience.” There is a prioritization of eurocentric masculinist epistemology. We present it as the only methodology of choice within journalism. Defining this methodology as the truth leads to the denial of lived experiences that fall outside of that truth.

Given who formalized the development of the scientific method, Francis Bacon, a white man who lived in Renaissance Europe, and other methodologies used to define truth in the United States were/are predominantly white men; the generalizations drawn from such methodologies tend to validate the experiences of these white men or white folks in general while neglecting or diminishing other lived experiences.

Simply put, we as journalists value statistics and other scientific or academic “facts” that tend to feed into the cis-hetero white male understanding and reality of the world. Then, we proceed to degrade counter-narratives — like the lived experiences of oppressed groups — labeling them as opinion.

Critic of Interviewing

The relationship between source and writer, and later between writer and reader, resembles the banking model presented by Paulo Freire in Pedagogy of the Oppressed [1968] in which Freire describes the perceived dichotomy between the student and teacher relationship — or in the case of journalism: interviewer and interviewee.

The “narrating subject” [the interviewee] is seen as the expert in charge of presenting the totality of information about any one given topic. The “patient listening object’s” [interviewer’s] role is to consume the information presented by the narrating subject without consciously processing it, given that a conscious processing of said information would yield unwanted bias.

Following, the patient-listening object [interviewer] turns into the narrating subject [writer] and the new patient-listening object is the reader. The writer is now viewed as the expert on a topic they have not critically thought about. As such, “the teacher [writer] talks about reality as if it were motionless, static, compartmentalized, and predictable. Or else he expounds on a topic completely alien to the existential experience of the students [readers]. His task is to ‘fill’ the students [readers] with the contents of his narration — contents which are detached from reality, disconnected from the totality that engendered them and could give them significance,” Friere writes.

The relationship between the patient-listening object and the narrating subject results in the removal, or absence, of humanity within the journalistic process. The interviewee is seen solely as a source of information — the validity in their being is determined by how much their experiences fit into the angle the writer is exploring. Once the transformation into narrating subject [from interviewer to writer] occurs, the writer begins to exploit the information entrusted to them. We are expected to turn an interview [let’s say about 30 minutes long] into one or two quotes. I, previously, did not stop to question, nor was I told to question, whether said quotes were representative of the entire interview as opposed to just the most controversial moments.

Moreover, I — the writer — have complete power over the framing of the interviewee’s information. By not viewing their words as an extension of their being or humanity, I do not perceive an inaccurate framing as harmful because they are viewed as detached. Their ideas become my prerogative to do as I please when I transition from an object to a subject.

Similarly, such an objectifying interaction occurs between the writer and reader. The writer presents the information as separate from themselves. There is an absence of speaking to their lived experience and naming their humanity. Consequently, the reader is forced to either accept or reject the information as the singular truth without knowledge of the writer’s existing biases — given that no single person is truthly “objective.” Moreover, there is a commodity and consumer relationship between the writer and reader. The writer must write the reality as seen by the reader in order to make a profit. This denies us, the writers, the space to go against the eurocentric masculinist truth.

Critique of Angles

Unquestionably, in my experience as a reporter for The Evanstonian, one of the most damaging aspects of the journalistic process is the existence of an angle within a story. A writer must take their constructed reality of a topic, once again depicted as the rectangle, and funnel that information — picking and choosing the facts most congruent with their angle — until we have developed a story that will get the most reads.

However, this story guides a reader to a specific conclusion about the general theme of your story, not just the specific angle. Thus, the reader finishes the story believing that the yellow triangle [the specific piece] is equitable to the smaller circle [all the knowledge the writer has about the theme]. In reality, it is not even equitable to the writer’s construction of understanding [the rectangle].

In addition, presenting the filtered version of the information as the singular truth negates the lived experiences and existence of those that exist outside of that truth. More likely than not, such negation would reinforce the marginalization and denial of truths of those exist outside of societal normalities in white America — those without privileges.

Features’ New Model

After examining traditional journalism, the section of feature is making a conscious decision to change our philosophy. These changes are not static. Rather, feature will exist in a constant state of evolution based on the experience of the writers within the section at any given time and the feedback from those outside of feature: like you.

Moreover, I would like to acknowledge the harmful nature that feature — and myself as a writer of feature — has existed as, given our blind acceptance of traditional journalism. Changes that are occurring now in no way deny the experiences born out of the past 101 years of The Evanstonian.

Feature is expanding our definition of what truth means — depicted as a larger circle in the new model. With special attention to the over representation of eurocentric masculinist epistemology that tends to exist within The Evanstonian, we are making space for multiple epistemologies to exist, depending on the writer’s agency. The epistemologies of each writer will be described on Evanstonian.net under feature members’ biographies, and when appropriate, as decided by the writer themselves in pieces.

For example, this would look like: Trinity Collins is the feature editor and this is her fourth year on The Evanstonian. She is a senior and hopes to study Secondary Education Social Studies and Journalism at college next year. As a writer, Trinity roots a majority of her articles in the lived experience of others, attempting to not prioritize data but people. Recently, Trinity has begun to integrate her own voice and narratives as truths as well. Additionally, she examines each theme through the lens of building her own social consciousness and awareness. Primarily, she is most interested in writing about social justice and inequities within the ETHS community, which is reflected in Trinity’s work.

A change in the methodology of feature must begin at the budget meeting [where writers decide what they are writing for a given issue]. Prior to proposing an article, we must ask ourselves, “am I the person to write this piece?” and “do I have the lived experience, identity or proximity to do this piece?” If one does not have the lived experience to localize the theme then born out of the piece is generalization(s). I have come to an understanding that it is better to not write a story than misrepresent a group or realities.

Following the budget meeting, writers next examine themselves in relation to the piece. For example, when I write about race, I am doing so from the perspective of the oppressor. I must be able to acknowledge that and name that in my pieces. This helps me figure out what narratives I have heard people share that I, myself, do not represent and where there are holes in the story — who’s narrative I have not sought out.

For myself, during the researching process, it is very easy to get caught up in believing that data are irrefutable truths. In effect, I enter into interviews only acknowledge was reinforces the data. Consequently, I disregard counter-narratives as statistical anomalies.

Inherently, there is nothing wrong with valuing data as your qualification for truth. However, especially given the nature of the section of feature — within The Evanstonian — was developed as a means of introducing humaninism into the newspaper, we in feature need to have a cultural shift where we do not use subjective data to belittle lived experiences because of their subjectivity.

Moreover, we must continue to humanize our interactions with interviewees. This begins with a shift in what we categorize as the interviewing process. First and foremost, not every story needs to have an interview — in the traditional sense. Second, interviews will now function as a conversation as opposed to an interrogation. We, as the interviewer, must be willing to humanize ourselves and engage in an non-academic, fluid way. This means speaking to our own lived experience, responding honestly, consciously and critically to what the interviewee has said. Finally, maintain lines of communication and humanization after the interview itself.

Once, we create this shift in thinking from “my source [note the possessiveness of that language] to “this is a human being,” we can begin to create a wantingness to accurately share their lived experiences.

Finally, on an editorial level, there is going to be a change in the way we edit — attempting to remove the objectifying nature of the writer’s pieces. Given the introduction of “I” statements and personal narratives, conversations about the content will occur in person [grammatical changes will occur on the document]. Moreover, various languages and dialects — including idiomatic expressions [not rooted in oppression] — would not be changed in order to uphold The Evanstonian norms.

During the copy-editing process, cut versions would be done by the writer or approved by the writer.

Guest Submission + Responses to articles

Feature needs to begin to establish a relationship with you, the readers; such that when stories does not speak to your reality as a human, you are able to write a letter responding. While there is room to disagree with the piece in its entirety, you are also able to agree with the piece and provide additional truths that represents you more fully than a piece written by our reporters.

I implore you to use feature as a tool to represent your voice — entrusting our writers or speaking on behalf of yourself. Also, please constructively criticize feature. Feature doesn’t have it all figured it out right now and we need additional support from you as readers to articulate our impact.