Exploring Experiences Around WiSTEM

Illustration by Aldric Martinez-Olson

April 26, 2019

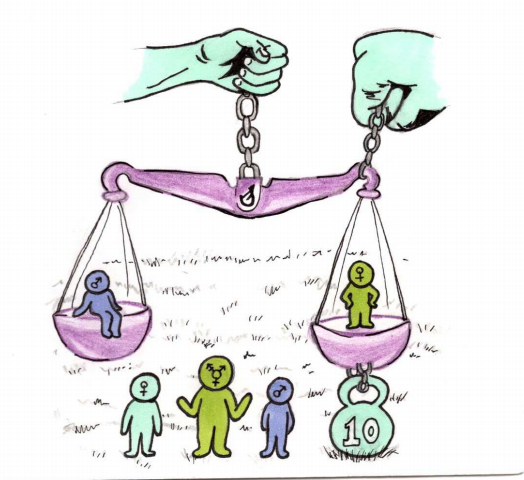

Since the beginning of modern society, the fields of STEM [science, technology, engineering and math] have been traditionally dominated by men. Starting at the turn of the twentieth century, that quota has been changing, and ETHS has been playing its part. The Women in STEM program [WiSTEM] has managed to empower hundreds of girls and start them on their journey to STEM futures. The program, which is derived from a partnership between Northwestern and ETHS, consists of two classes available to female students: Intro to Engineering and Design and Intro to Programming. The WiSTEM club is also an open space where female students can share their experiences in engineering classes.

When I first heard of these classes, a couple issues immediately came to my mind. I was concerned about gender identity: can those who identify as women but who are still listed as male in the school’s records sign up for this class? I was concerned about availability: what happens to the girls who sign up for women-only classes but get placed in the mixed gender classes (which are majority cis-white men) due to limited space? Finally, part of my bias came from my own experiences in heavily male classes. The majority of my friends are female, and even in mixed classes I tend to gravitate towards the girls in the class. In my freshman PE class, my femininity naturally alienated me from my peers. How would I, an anomaly to the “system,” conform to this space? I’ve always been interested in engineering, but this question is what originally steered me away from taking engineering classes.

As it turns out, this situation of gender expression influencing course decisions is not unique. Kris Bostick, a sophomore, had to consider his own gender expression during course selection. Bostick currently identifies as Bigender. As an incoming freshman, he had not fully come to terms with his gender. His parents suggested the WiSTEM class, justifying it by saying that they did not want him to have to deal with “the domineering male personality.” But this was not what Bostick had in mind.

“That made me feel uncomfortable because I don’t want to be in an all women’s class. I want to be with the dudes. I have to get used to it eventually so why not just do it now?” Bostick stated.

Junior Misha Peterson had a similar experience; “I was out, but my parents didn’t quite get it. They were like ‘maybe you would like to go into the women’s class,’ and I said, ‘no because I’m not a woman, so that wouldn’t be for me.’”

Bostick did not end up taking the class and Peterson eventually dropped it. However, as the interview progressed, I discovered that the decision not to take it was based more on scheduling than on gender. For Peterson, it was simply too much of a trek from deep in the art wing cut to the gym wing. And for Bostick, the class wasn’t going to fit smoothly into his schedule.

A scenario I had envisioned was a non-conforming or transgender student who would’ve felt more comfortable in an all women’s space, but was not able to sign up due to the school’s policies. The current policy allows students to fill out a student advocacy form that allows them to access gender-neutral restrooms and locker rooms, attend gender-specific clubs or sports, and communicate their preferred name and gender preference to the school. However, to change the official name and gender listed on the school’s records, parental consent must be given.

Throughout this process, the student works with Taya Kinzie, the associate principal for student services. Kinzie affirms that although the class is designed for women, the school’s official gender record shouldn’t stop a student from being where they’re most comfortable.

“How we make sure we are creating the right space for everyone, that’s really something we’re going to have to take on a case by case basis,” Kinzie states. “More lobbying has to be done around that to make sure we have the capacity for everyone’s identity.”

Compared to surrounding schools, ours is unique in its inclusive practices. The school has an LGBTQ+ advisory board, a collection of 24 staff members who discuss the school’s issues regarding gender and sexuality. Other schools, mainly Niles North and New Trier, simply don’t compare. While they both have support groups for LGBTQ+ students, ETHS makes it clear that transgender and gender expansive students are supported under the “Equity and Excellence” section of the website. During my search, it was easy to find ETHS’ supports, whereas I had to dig through the databases of the other schools to find theirs.

WiSTEM classes were created as a safe space for women: a way to introduce them into fields where they are traditionally underrepresented. And they have done just that. Before the classes were implemented, Cynthia Curtis, an engineering and programming teacher, noticed the bleak realities of gender inequality; “In the five classes we had, we had about 15 females total. So two to three females in each section.”

The first year the class was implemented, the number of women enrolled in STEM classes nearly doubled to 27.

“That opened up what we call a pipeline, allowing women to see if this is a path they want to take or not. It allowed exposure to happen,” Curtis says. Since then, the number of girls enrolled has only been increasing.

Junior Kelsey Aquino talks about her experience in her women-only class. “It wasn’t as intimidating as any other classes I’ve had because we all identify as women.” Aquino is a current student of Principles of Engineering, which is only offered as a mixed-gender class. While the number of boys outnumber the girls, there is still a heavy female presence, which could be an implication of the all-female classes. Regardless, Aquino’s experience in her original class was undoubtedly positive, and she’d like to see more of these classes implemented in the future.

Senior Audrey Freeman brings up a positive of mixed-gender classes. “When you are completely segregated, it ruins the purpose of why you wanted girls there in the first place. The first step is getting girls involved but then, if you are a guy and you never experience working with girls, then later on in the workforce you’d be like ‘what’s going on? I’ve never had classes with girls. Girls do engineering?’”

It is a fact that STEM careers are majority male. It’s not right, and it’s not ideal, but it is a fact. Freshman Joanna Tafolla took diversity into account when selecting her classes.

“I didn’t apply [for the all-female class], because I thought it was not as diverse. I thought there was going to be more of a mix in the other class.”

While it is important to work and learn in diverse spaces, it can be hard to encourage girls to sign up for traditionally male-dominated classes, and WiSTEM has proved to be part of the solution. Amaya Bonn, freshman, was an exception to the pattern; she put the mixed class as her first choice and the all-female class as her second.

“They should approach more girls because I think a lot of people are interested but they’re scared of being the only girl in the class,” Bonn adds. “Or, they should have more opportunity with all girls classes so they can feel more comfortable.”

At the moment, only two classes are currently women-only: Intro to Engineering and Intro to Programming. At the higher levels of engineering, classes become mixed again, allowing for all genders to work together. These classes are populated by sophomores and upperclassmen, and by that time, most students have gotten comfortable with being around genders different than their own.

Last year’s seniors noticed a troubling pattern between the males and females of Chem/Phys was taking place. Freeman explains, “a lot of girls would drop [Chem Phys] after sophomore year. A girl would get a higher grade than a guy but the guy would continue and the girl wouldn’t: a weird discrepancy.”

Fortunately, the students took the initiative against this trend. They created a tutoring program where juniors and seniors from ¾ Chem Phys tutor sophomores in 2 Chem Phys. If you are more comfortable with a female tutor, you can request one. This provides an alternative space to ask questions without having to feel uncomfortable. While the program is primarily for Chem Phys students, expanding it to other STEM classes could be greatly beneficial. Another available resource is the Women in STEM club. The club meets once a month, and allows for upperclassmen to provide honest feedback to underclassmen about the classes they’ve taken.

“[The club is] girls helping girls,” Freeman says, “or anyone who doesn’t identify as a white male.”

When I first approached this topic, I had the intent of exposing all the negatives of Women in STEM classes. It’s not that I couldn’t see the benefits of them, but I couldn’t help but think of scenarios where people could possibly be excluded. Part of this intention came from my personal bias; I enjoy being in balanced-gender spaces. While interviewing for this topic, I realized the scenarios I had envisioned where a lot less common than I thought; I saw just how much good these programs were doing, and finally, I understood more lucidly the difference between equity and equality regarding gender issues.

Not everyone is going to need the same resources or environment while learning engineering, especially a group that has been discouraged from STEM for so long. These classes provide the equity that many girls need. Yes, some students won’t have as great of an experience in their own classes, but it is ultimately creating a future that will benefit us all. While there is no clear solution to this complex issue, I think ETHS is developing one. Women-only introductory classes allows for girls to be introduced to science, technology, engineering and math while they are underclassmen. As they become upperclassmen, they can choose whether they want to continue in these fields or not. If they do, they’ll have additional support resources such as the WiSTEM club and peer tutoring. If other schools around the country adopted a system like ours, it could slowly, but surely, close the gender gap in the fields of STEM.