Still Love These Lonely Places: A Hauntological Analysis of Evanston

April 26, 2019

Chief Seattle may or may not have said…

“The young men, the mothers, the girls, the little children who once lived and were happy here…still love these lonely places. And at evening the forests are dark with the presence of the dead. When the last red man has vanished from this earth, and his memory is only a story among the whites, these shores will still swarm with the invisible dead of my people. And when your children’s children think they are alone in the fields, the forests, the shops, the highways, or the quiet of the woods, they will not be alone. There is no place in this country where a man can be alone. At night when the streets of your town and cities are quiet, and you think they are empty, they will throng with the returning spirits that once thronged them, and that still love those places. The white man will never be alone…The dead have power too.”

Part 1: Ghosts

“Invisible things are not necessarily not-there.” Toni Morison’s 1989 statement is one of the most crucial theoretical arguments of our time. At first glance, Morrison’s statement seems sort of obvious. Whether it’s in movies, video games or comic books, people who turn invisible are still “there,” they just can’t be seen. When Harry Potter went under the Invisibility Cloak, he wasn’t suddenly wiped from existence or “not-there.” But, Morrison’s point digs deeper than fairy tales and fantasies to something much more significant than that. It’s about ghosts.

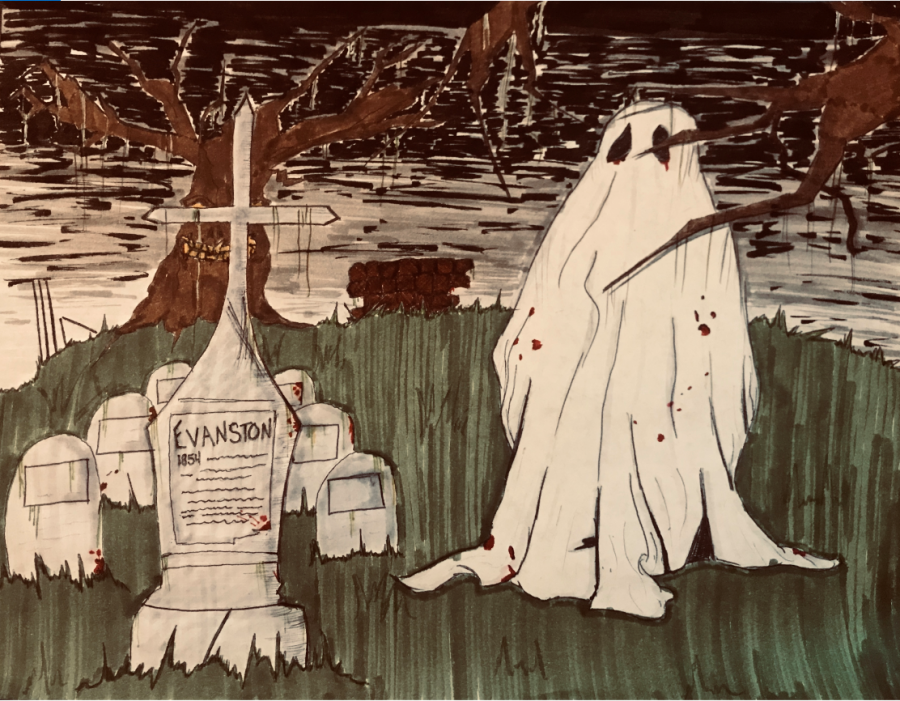

While Morrison probably wasn’t talking about little kids with large sheets over their heads and two small circular cut outs, she could have been. When we speak of ghosts, we speak of many things. We speak of the dead, the living and those yet to be born. We speak of the forgotten and the remembered. We speak of those not visible, and those hypervisible. We speak of the abused and the abusers. And most importantly, when we speak of ghosts, we speak of haunting.

Avery Gordon, in her seminal book Ghostly Matters, writes,“haunting is… an animated state in which a repressed or unresolved social violence is making itself known… those singular yet repetitive instances when home becomes unfamiliar, when your bearings on the world lose direction, when the over-and-done-with comes alive, when what’s been in your blindspot comes into view.” Gordon establishes haunting as the complex sum of social, political, psychological and otherworldly forces that cry for a “something-to-be-done.” Haunting can arise in the recognition of these forces, but also the unrecognition. The absence of a person, a place, an event, a force can be the presence of a ghost. Within haunting absence is presence, and presence is absence.

Haunting is also complicated, and deeply implicated in power. The children who are abused growing up are haunted by their parents as they continue the violence onto their kids as parents. The ever present violences of neoliberal capitalism haunt every time we walk past a homeless person on the street. Every time Black people repeat Black Lives Matter, they haunt America, confronting the unending system of slavery. And that system of slavery, both physical and metaphysical, continues to haunt America, as it disrupts and continues to alter the possibility of black life within the status quo. Indigenous people haunt settler colonial governments every time they continue to assert their right to land and sovereignty, and settler colonialsim continues to haunt indigenous life as cycles of suicide, drug abuse and domestic violence ravages reservations. Power, ultimately, is haunting.

Evanston is haunted. It is the spectre of those murdered at the Sand Creek Massacre — an event that is integral to the conceptual framework of Evanston — who walk our halls, and roam our streets. It is the living deaths of Black subjects who lay the foundation for the human subjects who occupy Evanston. As a product of the 2016 presidential election, liberals popularized the term ‘the Evanston bubble;’ the Evanston bubble is preserved by and through the violence performed onto these communities. The bubble is a ghost.

Part 2: Anti-Blackness

What if we consider haunting as not only the experience of a ghost living with and through the living, but the living, living through and with a ghost? In her revolutionary mapping of the Middle Passage, professor Saidiya Hartman theorizes the violences that Black people experience ‘after’ the Middle Passage and chattle slavery as “the afterlife of slavery.” It is this understanding of violence that is helpful in deepening our understanding of Blackness in relationship to the hauntological. Haunting is not an event, a location or a process; it cannot be fixed to a location or understood in a singular or static relationship to subjects. Instead, to be haunted is to live with (and through) the aftermath of the irreconcilable, the misunderstanding of the unknowable and misinterpretations of the unspeakable.

This aftermath of a lived death is seen best in the relationship that President Barak Obama had to the death of Trayvon Martin. In a press conference shortly after the shooting death of the 17-year-old in 2012, Obama stated: “It is absolutely imperative that we investigate every aspect of this.” It is in this phrase, spoken by the president, that begins to expose the hauntological construction of the event. How do we “get to the bottom” of a death of a black child? How do we “get to the bottom” of the world’s desire to erase and consume Black death? How does the family of Trayvon Martin “get to the bottom” of the empty seat at their dinner table and the open bed in their home? The ghost of Trayvon, the ghost of the living dead, the ghost of the ‘after life of slavery’ makes up the lived reality of Black people everywhere. It is the ever presence of death, the intimacies of nonlife that shape the orientation the Black subjects have to the world.

Others in the literary field of Afro-Pessimism make the argument that the world is constructed in relationship to the perpetual gratuitous violence that the world performs onto Black people. The hauntological shows us that it is not only the social, but the ecological and biological world that reflect violence onto Blackness. Alex Kotlowitz, in a series of interviews and narratives about gun violence in Philadelphia, builds a picture of inner city life. He articulates on instances in specific that helps us understand the role of hauntology in lending us a deeper articulation of violence, Kotlowitz writes, “Another young man told me that whenever he passed the spot where he was shot, he thinks he sees himself on the ground writhing in pain, and he approaches the specter to assure himself that he’ll be O.K.” It is the haunting of time and space that fix the Black subject to its relationship to violence.

When thinking of those consumed by haunting, the character Dick Hallorann, from Stephen King’s film The Shining, comes to mind. There are many things that make Hallorann unique; for starters, he is a chef at a haunted hotel that seems to have almost no one to feed. He is telepathic, and he is Black. It is the accumulation of these three characteristics that make his life defined by hauntings. The hauntings of the hotel in which he lives ultimately lead to the destruction of his body. He knows that his biological life will end as a result of the haunting, but he also knows that his ontological capacity, his spirit, will preserved through the haunting. He is present with the haunting that has made and will unmake infinitely and incalculable, his life. Instead of a flight from the presence of the hauntings that created him, he instead embraces and becomes one with the haunting. It is this practice, the one of sitting with the ghosts, that become the only option in the face of a life defined by the unnatural, the supernatural and the extranatural. Our only possible praxis becomes one that allows us to occupy the world through the haunting and the haunted.

Part 3: Settler Colonialism

A specter haunts Evanston. The specter of Indigeneity. The Patawatomi and Miami still walk “the fields, the forests, the shops, the highways, [and] the quiet of the woods” of this land. This physical material place of earth we call Evanston is haunted, but so is its metaphysical being– its ontological being. We are haunted down to our very name.

In 1787, the United States signed the Northwest Ordinance with a number of Indigenous tribes within the Great Lakes region, promising to never invade, steal or take their land. This false promise has haunted US-Indigenous relations within the region to this very day. Just eight years later in 1795, the Greenville treaty was signed with the Miami, tricking them into giving up mass amounts of lands in the region, devastating tribal life. In 1833, the Potawatomi were forced into signing the Treaty of Chicago which unfairly granted the federal government 5 million acres of Potawatomi territory. In 1838, the Potawatomi were forcibly removed from this land in the Trail of Death, in which villages were burned, and many people were killed. In 1846, the Miami were forced again into signing the Treaty of Wabash, moving them from the Great Lakes to Mississippi. In 1864, John Evans, then current head of Indian Affairs in Colorado, ordered military to massacre 400 Cheyenne and Arapaho women, children and elders on the Sand Creek River. This act cleared the land for John Evans to make more money and resources, which later helped fund Northwestern University and the founding of Evanston. The same lies, violences and betrayals of settler colonialism haunted this land over and over again. Treaty after treaty, lie after lie, cycles of violence reproduced themselves in order to found Evanston. We are haunted down to our very being.

This haunting is not unique to Evanston; the same specter haunts America. Wherever you walk, the violences of genocide, anti-blackness and settler colonialism reek from their ever present, ever persisting graves. The smell of this 500 year assault is unbearable to the settler. Influential queer indigenous scholar, Jodi Byrd, writes within her seminal work Transit of Empire, “in the United States, the Indian is the original enemy combatant who cannot be grieved.” Settlers are unable to truly grieve the violences of anti-Blackness and settler colonialism; in fact it is impossible. If the settler psyche were able to absolutely digest the founding of the nation, we would collapse instantly, screaming in pain, drowning in a black hole of sorrow — for the settler would finally understand the terrorizing immorality, that is the creation of their being.

The ghosts know this. Hauntings of settler colonial violence call to the invalidity of the nation, the ultimate truth that the United States ought not exist. In a world in which immorality is always painted onto Indigenous peoples, their hauntings prove to have the most transcendental moral claim: to call out of being the United States. Eve Tuck and C.Ree, famous Indigenous critical theorists, in “A Glossary of Haunting,” note, “haunting, by contrast, is the relentless remembering and reminding that will not be appeased by settler society’s assurances of innocence and reconciliation.” No form of reparations, policy changes, land return, cultural recognition or liberal awareness is able to make the United States moral. No exorcism of our past demons will save us. The ghosts will just return. Haunting does not hope to “reconcile” settler colonialism; it hopes to “relentlessly remember” it. Tuck and Ree further, “haunting lies precisely in its refusal to stop.” Haunting is a constant refusal to accept moves to innocence by the settler, and to continue to call out of being the United States.

The haunting will not end until we do. That is why Eve Tuck and C. Ree admit, “I don’t want to haunt you, but I will…I am a future ghost. I am getting ready for my haunting. ” The liberal platform of reform and reconciliation will only continue to make indigenous people into ghosts, while simultaneously renewing and recycling the haunting violences of settler colonialism in daily life.

Our only option as settlers is to sit within this haunting. We mustn’t run from the ghosts, exorcise our nation’s demons or drive out the specters. We must communicate with them in a seance of refusal. Sitting within the haunting means curtailing our actions to the notion that our very being as a country is immoral. It means acknowledging that everything around us is built out of the bricks of genocide. Seancing with the ghosts of settler colonialism is a self-recognition of eternal guilt. A refusal to be innocent. A refusal of reconciliation.

Part 4: Sitting

Within Evanston, to refuse means refusing “Evans”ton. It means refusing to occupy this space in comfort. It means understanding that John Evan’s violence are not all too different from our own. It means sitting within the hauntings and specters of the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Potawatomi, Miami and Illini who still love these lonely places. It means not falling into “woke” cultural where critical comments, insights and stories earn white people spaces of innocence where they can feel good about themselves. It means abolishing the liberal bubble that allows white people and settlers to block out the ghosts and hauntings that create their very being. We must allow the ghosts to burst the bubble, and the specters to invade inside. We must welcome the ghosts in, have meaningful conversations with them over coffee and invite them to dinner too — understanding throughout that these ghosts of our country’s violence will never go away.

Western epistemologies ask us to understand ourselves, after the erasure of our physical bodies, in relationship to ‘the mark we leave on the world.’ Hauntology is instead the understanding that our identities are comprised of the marks that the world leaves on us. The ways in which violence is recycled, restructured, repurposed from one generation to the next and one world to the other. The only ethical option is to open our homes, hearts and lives to the ghost. To refuse the desire of getting past, getting over and getting though hauntings, to instead arrive at a deeper understanding of the ways our identities and the spaces that we occupy are made up of violence — violences that can’t be understood, articulated, reconciled or redeemed. The ghosts didn’t ask for a Black president. Nor did they ask for the 13th amendment, the civil rights movement or Roots. Instead they call for us to call to the unspeakable, wade in the worrisome and grasp the intangible. In doing so, we begin to build a deeper picture of the world more in touch with the haunting that make us who we are. The Black Mothers who haunt Audre Lorde’s 1985 essay Poetry is Not A Luxury tell us “I feel so I can be free.” It is through the method of feeling that we begin to rediscover the powers that perpetually make and unmake the worlds in which we occupy, as a means of transcending this world taking us to the gratuitous freedom of the next.