Teachers, schools provide emotional support for students

December 13, 2019

Recently, the Chicago Teachers’ Strike put nearly 300,000 Chicago Public School (CPS) students out of school for 11 days. CPS teachers were striking for reduced class sizes, salary increases and an increase in support staff in CPS schools, according to The New York Times.

“The thing with the CPS Teachers’ Strike is that these teachers were demanding things like paraprofessionals in classrooms or in ESL classes, and demanding mental health professionals in the building to help students,” says Civics and Humanities teacher Yosra Yehia, who previously worked in three different CPS schools. “That was something I noticed also at this school [in CPS]. Although it was a lot better [than others], I didn’t receive training. I didn’t know where to direct students to mental health professionals in the building.”

The Chicago Teachers’ Strike also becomes a more nuanced issue when looking at the sheer size of the CPS district. According to the CPS website, the CPS district is the third largest in the country. However, the class sizes and varying access to resources among CPS schools don’t ensure an equitable education for all. For example, 77 percent of the graduating class of 2020 receives free and reduced lunch, highlighting the inequities within CPS schools.

“[Illinois] actually created a law saying that Chicago Public School teachers can’t advocate for lower class sizes in the bargaining because they know it will cost a lot of money if they lower the class sizes. I remember at Lane Tech I had classes near 40 [students]. It was challenging,” says video production teacher Amy Moore, who worked in Chicago Public Schools for 15 years.

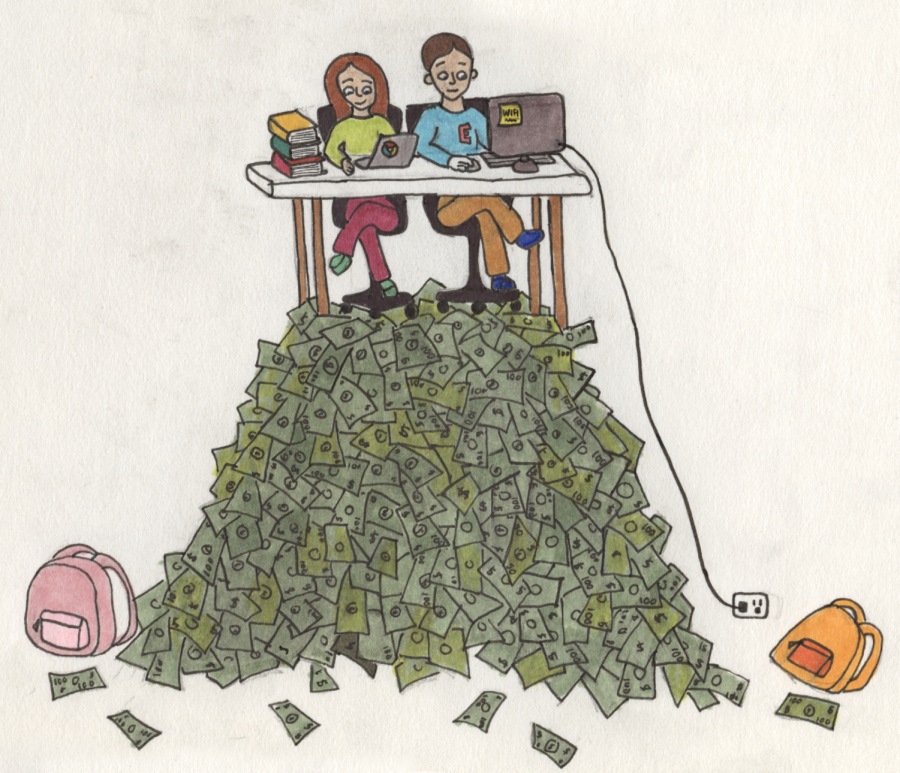

Class size and access to resources such as support staff are factors that can greatly affect students’ overall performance in school, according to studies conducted by the Goldman School of Public Policy at the University of California Berkeley. However, according to Brookings, a nonprofit public policy organization, increasing class sizes by one student nationwide would decrease the teacher workforce and would result in saving $12 billion in the cost of teacher salaries alone. This money would go to the influx of teachers that would need to be hired in order to accommodate smaller classes.

This is not the case for every district; the average class size in Illinois is 22 students. That said, according to Illinois Report Card, ETHS boasts small class sizes, with an average of only 15 students per class.

Districts that earn more funding, whether that be from fundraising, taxes or other donors, are better able to support classes with fewer students, while less affluent districts are not always able to offer smaller class sizes complete with the associated resources.

Although some school districts, such as CPS, may simply be unable to afford smaller classes, there are other ways in which teachers can ensure that their students are performing to the best of their ability and feel supported in school, regardless of class size.

“[My classes] do that. We find meaning [in the class], and we talk about different issues that are taking place in the classroom. I think we can get better at it, but I can see the difference of creating a voice so students can feel like they are the class,” says math teacher Jose Arias, who previously worked in District 300 in Algonquin, Illinois.

Additionally, the ways in which schools and teachers support their students might be modeled differently in varying districts.

“If I could compare District 300 to ETHS, you can definitely see the difference in resources. It was clear,” says Arias. “It starts with little things, like the events that we have here at ETHS [that] would never happen in that school.”

Another way in which many schools have begun to support their students is by implementing social emotional learning into the curriculum. Beginning with a meeting hosted by the Fetzer Institute in 1994, social emotional learning (SEL) has been emphasized in many classrooms since. SEL is a process through which children are taught skills to cope with trauma, manage emotions, maintain healthy relationships and make responsible decisions.

Social emotional learning offers both an opportunity for students to learn about themselves and connect with their peers. According to the National Education Association, effective SEL programming begins at the early childhood stage and continues through a student’s high school career. The effects of proper SEL programming are monumental for a student’s career, with data proving that the best SEL programs establish an understanding that education is truly meaningful when there is a joint understanding of emotions and a mutual respect for both the teacher and the students’ lived experiences.

“I know that ETHS is pushing student advocacy and student voice and that is something I’ve noticed in many classrooms here, where teachers are trying to create more room for student voice. That’s not the case in all schools in the Chicagoland [area], I’ll say. That culture, I think, is unique to ETHS,” says Yehia.

Proper social emotional learning programs are also designed to strengthen the relationship between the teacher and the students, with an emphasis on creating a trusting and accepting space for all, according to the above National Education Association study.

“I think [students get] a sense of confidence, a feeling that they can be successful, that people believe in their potential and capability, and that it’s just a nurturing environment for them,” says Moore.

The intentionality of social emotional learning is to establish a space with healthy relationships, allowing teachers to know their students on a more personal level. Additionally, an emphasis on a close teacher-student relationship in the realm of social emotional learning is another way in which students can feel supported and valued in the American education system.

“Last year especially, I was really nervous because it was freshman year. I realized how vulnerable I was, and a lot of teachers saw me in a different light,” says sophomore Lucy Garcia. “My humanities teachers especially saw me open up more. I opened up to them about my struggles and they kind of reciprocated that same emotion, so I feel like we had a connection.”

Although there is certainly a large emphasis on supporting students’ needs beyond their education, not acknowledging the privilege that often accompanies this sort of education would equate to me not acknowledging my own privilege as the writer of this piece. As a student at ETHS, I feel fortunate to be receiving an education that I feel is comprehensive and to have formed close bonds with both adults and students in the building. However, as a white-identifying student, the education system is designed to make the formation of those relationships easy for me. The same sentiment is not true of every student nation-wide, or even within ETHS. Although it may seem easier to reflect on these complexities without truly evaluating our institution, that mentality can be toxic for those who struggle under the seemingly unnegotiable pedagogy of what education should be.

As a white student, there are many spaces in the ETHS building in which I inherently feel accepted. Regardless of where those spaces are, it is important to note that there are certain spaces in our institution that have been created to serve white students, the same way that the literature we are exposed to often revolves around white protagonists and the history we learn often silences the voices of POC activists.

The way in which our institution is currently regarded and upheld cannot possibly honor everyone’s history and experiences in a way that is equitable. This inherent inequity is yet another way in which the “worth” of students and their education varies. However, some students and teachers feel that it is important to diversify our curriculum in order to honor the lived experiences of as many students as possible.

“As a Black Muslim girl, we had a Ramadan holiday during a final exam last year and yet we didn’t have a day off and had to come to school during that time,” says sophomore Soumia Kaltimi. “We need some changes in our curriculum, especially when it comes to religious beliefs.”

According to Giving Compass, a philanthropy knowledge organization, teacher requests for an increase in material that reflects their students’ lived experiences has increased by 117 percent since 2016. Later on, Donor Choose, a nonprofit crowdfunding platform, went on to begin the #ISeeMe campaign, a campaign dedicated to increasing the amount of varying resources for teachers in attempts to make more inclusive spaces in schools.

“Things like AM Support, Wildkit Academy, all those things I think really help you [teachers] help students get caught up. And, they’re built into the structure here,” says Moore. “I think the school [ETHS] definitely thinks about strategies for helping kids succeed.”

The push to begin this visibility campaign was based on a study done by Gloria Ladson Billings, a teacher educator at the University of Wisconsin, which showed that when students who have been traditionally less successful in school see themselves reflected both in the curriculum and in their teachers, their achievement and active engagement improves. Students feel a heightened sense of belonging when their teachers deviate from the standard curriculum, which may include homogenous narratives. However, some ETHS students have yet to feel that increase in representation.

“I’m very, very proud of my culture and where I come from and my roots. But I’ve seen how under-represented students feel, not being able to talk about their own struggles,” says Garcia. “It makes it hard to apply your own life to some of the things that we’re reading.”

That said, some students may also see a shift in their level of engagement in a class when a teacher creates a space in which students feel supported.

“This year, it feels like they’re [students] more engaged in what they’re doing because they see that this is their class and they take a little more ownership,” says Arias.

Many students believe that with emotional support from teachers and active engagement from students, classrooms can become a more productive, mindful and cognizant space for all.

“[When a teacher gets to know me], it makes me feel like my existence matters. I matter and so does my voice in the space,” says Kaltimi.