Social media decade: shaping the 2010s in our memories

January 31, 2020

After 3,652 days, 120 months, and 10 years, the 2010s decade is in the books. So much time, and so many memories that all of us who lived through the decade have experienced. Even if at the surface it’s just a slight digit change on our calendars, the end of the decade often begins a time of cultural self reflection. We ask ourselves what we accomplished this decade as a society, but perhaps more specifically, how we’ll remember those accomplishments in the years to come.

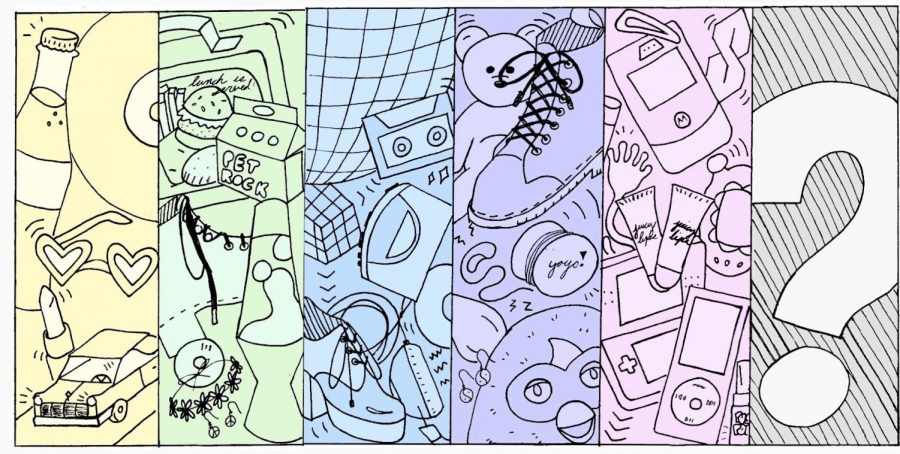

Since World War II ended and the modern world evolved into what it is today, each subsequent decade has had many labels with a certain cultural sentiment attached to it. There was the booming and stable 50s; the rebellious and progressive 60s; the continued activism and economic downturn of the 70s; the innovative, conservative, and “aesthetic” 80s; the alternative and prosperous 90s; and as we increasingly search for an identity of the most recent past decade, the 2000s, most would call it the decade of the rise of the Internet, with most pop culture beginning to transition to the digital world.

Now all of those are massive generalizations. A decade can’t accurately be described with just two words, but we generalize time periods so often that it doesn’t seem out of place. These generalizations are also not reflective of the decade itself, but fall closer to how we romanticize it in the present day. And that brings us back to our current decade. Now that it’s nearly over, how do we identify it on that list, even if we’re generalizing? Specifically for Generation Z, the spin being put on this by many is that the end of the decade represents the end of “our childhoods” for those of us currently in high school, who would’ve spent a significant portion of our childhood living in the decade.

Intertwining certain events and social developments with the decades they occurred in, and subsequently identifying the decade as a whole with them, is something that has been going on for many centuries, but since the Second Industrial Revolution and the rise of consumerism, it’s been much easier to associate decade identity with the more consumer aspects of the decade, which often means pop culture. The 1920s are perhaps the first good example of this. “The Roaring Twenties” is such a common term associated with the decade that it’s been brought back into the common lexicon now that we’re in the 2020s. It generally describes the era’s booming economy in the U.S. at least, which combined with the birth of mass culture and consumerism, can be attributed to everything else the decade is known for today. Perhaps the most significant political development of the decade was women’s empowerment, starting with the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote in 1920, to the the eventual image of the flapper: “liberated” young women who drank, wore short skirts and bobbed their hair. Even if flapper culture didn’t affect everyone, the image of flappers certainly existed as the rise of mediums such as radio, film and nationally distributed magazines throughout the decade allowed it to get into the minds of people during the time. The popularity of jazz music is another commonly accepted feature of the 1920s zeitgeist. These ideas made the 1920s probably the first decade where the identity had to do with pop culture, especially seeing as the first two defining characteristics of the era that come to mind have to do with fashion and music, respectively.

This cultural image didn’t last throughout the entirety of the 1920s, as the end of the decade is seen as the start of the Great Depression. While the Great Depression began within the 1920s, August 1929 to be exact, the last few months of 1929 may as well have been part of the 1930s the way we remember anything that happened then, and this represents what often would be seen in future decades: a point of divergence between the calendar and what we associate with the decade. It can’t be avoided, as history doesn’t happen in a linear fashion, but more extreme examples of this would occur as the 20th century progressed to the point at which one part of a decade might be completely unrecognizable culturally from another.

The 1930s and 1940s are kind of an afterthought when thinking about the cultural definitions of decades. The major global events we associate with those decades, respectively, were the Great Depression and World War II. The idea of cultural decade identities resurfaces, however, when looking at the end of World War II.

“My attitude is when we’re talking about the ‘50s, mostly what we’re talking about is the era after World War II, which begins in 1945-46. It isn’t really a decade, but the idea of prosperity, safety, white flight and the civil rights movement, we kind of collectively think of as the ‘50s,” says history teacher Jay Stanek.

With the ‘60s, people can have an even more skewed image when comparing the full scope of the decade to how they remember it, with most of what comes to mind when thinking of the identity of the ‘60s occurring in the later part of the decade.

As Stanek adds, “I think when we think about the ‘60s, what we’re really thinking about is the late ‘60s. We think Woodstock, and hippies and Vietnam protests. That’s really 1966-70 or so.”

Events in the early part of the decade, like the assassination of John F. Kennedy, can often dim in comparison to the activism-centered latter half. This does at least provide us with a solid example of a decade where youth culture is primarily what we remember.

“I feel like youth culture, kind of always, but especially in the late 20th century, was about rebellion, and still is. The first thing that came to mind was in the 60s, with the Vietnam War, youth culture revolved so much around protests and riots,” says senior Ananya Visweswaran.

The ‘70s are less well defined than some of the decades before them, perhaps because some of the major events returned to being less social and more political, with events like Watergate being among the first to come to mind.

On the zeitgeist of the times, Stanek adds, “The stereotype I think with the ‘70s, when I was born, is that this is the ‘me’ generation, that all this ‘trying to fix the world’ stuff failed, and now we’re inward looking and self-absorbed.”

Moving on to the ‘80s, it was another particularly important decade politically, but with the economy turning back up, pop culture was strong again and it’s easy now to remember the decade’s pop culture contributions, from MTV to blockbuster films.

As Stanek puts it,“[With the 80s] the stereotype [was] more self absorption, but a more ‘world-affirming’ one. Of course, it’s the era of Reagan and Reaganomics and deregulating the economy, focusing on the needs of business and things like that.”

The ‘90s continued the trend of decade identities associated with strong pop culture from a good economy, albeit with its political drama most would remember, such as Bill Clinton’s impeachment.

“Most people think of the ‘90s as a relatively prosperous time. It’s just the economy, all of this money that we were spending fighting the Soviet Union, we didn’t have to spend that money on defense anymore, so the money could go to other places,” Stanek adds.

The 2000s could be seen as an end to that prosperity, with the major global events we’ll remember for decades to come including 9/11 towards the beginning of the decade, which dramatically shifted the mindset of prosperity of the last couple decades to that of fear and the War on Terror, and then the Great Recession towards the end of the decade. Culturally speaking, the 2000s began the slow rise of the Internet from a development some had been familiar with and used, to the necessity of modern life we see it as now.

“The Internet was a thing, I knew about it. I don’t know if it was changing my life dramatically in the 2000s. Fast forward to 2010, in this last chunk of time, I think social media has just transformed the way we interact, the way we think, and it’s hard to sort of measure in real time the impact of all this,” Stanek adds.

Now arriving at the 2010s, as we search for the identity of the decade that has only been over for a month, it’s hard to think of another cultural development as monumental as the development of a fundamental communication game changer like social media over the course of the decade.

As Stanek adds, “I would probably say…social media changes the way that we connect, or that we don’t connect. As long as we’re friends on the Internet, we don’t have to actually speak to each other, and we just find ourselves scrolling.”

Social media is not a development that was born in the 2010s, but it is one that grew rapidly and grew much more important culturally within the decade. According to a 2019 study by Pew Research, 69% of U.S. adults were on Facebook in 2019, up from 54% in 2012. Facebook’s user influx over the course of the decade parallels that of social media as a whole; while it was around at the start of the decade, the last 10 years have allowed social media to truly define its place in our society.

“I’m not sure how I would define [the 2010s], but [it is] this idea of being in contact with the rest of the world, having the world at your fingertips, the Internet becoming extremely accessible, especially to American kids,” says Visweswaran.

Facebook went from a relatively widespread, still immensely successful platform in certain demographics, to much more of a global phenomenon, and social media has seen a similar rise. Instagram, which was purchased by Facebook for $1 billion in 2012, launched in December 2010 and is perhaps more of a product of the events of the decade than its parent company, given its launch date being well within the decade. Instagram is estimated to have one billion active users worldwide, much more of which are young, also making it better representative of the decade’s youth culture trends as 72% of teens use Instagram, compared to only 51% who use Facebook, according to a 2018 study by Pew Research.

As social media evolved and came to be a massive part of the zeitgeist of the 2010s, along with it came a class of people that could gain a following. Celebrities who have become famous via means outside of social media, such as singers and actors, still are among the most followed people on social media platforms like Twitter and Instagram, but their leverage on these platforms is nowadays understated compared to that of the influencer. An influencer is typically defined as an individual that has the power to affect the purchasing decisions of others because of their authority, knowledge, position, or relationship with their audience, as pulled from Ingrid Halverson’s article that goes into more depth about influencer culture. A traditional celebrity could also be defined as an influencer, seeing how celebrities have frequently been used in advertising historically.

“I think it might have expanded so it’s not just a few people in the spotlight, like Marilyn Monroe, Frank Sinatra, now there’s so many different products out there that have all these different people associated with them,” Visweswaran says.”

At the surface, the only difference between a celebrity and a social media influencer could be seen as that one grew their following on social media and one didn’t. However, there is a much more significant difference between the two, one that has its roots in the generation that came of age during the 2010s. For one, influencers can seem more authentic than traditional celebrities because they often show a more personal side to themselves in their content. The most representative genre of content of this is that of the vlogger, or video blogger. Vlogging, one of the largest subgenres of content on YouTube, generally showcases the creator taking its audience through events in their daily life. From a business standpoint, all this makes influencers that amassed a following on social media a much more lucrative option for targeting young people with ads than traditional celebrities.

However, the way influencers can be monetized via advertising deals only tells the story of why they can continue to exist from an economic standpoint. The real value of influencers isn’t their ability to advertise; it’s the content they produce and the generations most active on social media, Millennials and Generation Z, typically consume. This is where the definition of an “influencer” can be stretched a little, as the typical image of an influencer is a model that primarily advertises fashion on a platform like Instagram. I’d personally describe there being much more to an influencer, spanning platforms and types of content. Not every single Internet or social media user consumes the same type of content, but most, if not all, consume content made by others in some form.

As Visweswaran puts it, “There’s all these other non-traditional ways of becoming an influencer. You don’t just have the movie industry, music industry and traditional modeling industry anymore; you have YouTubers and Instagram models and all these people that have immense popularity.”

I’d define an influencer as anyone who has grown a large following on a social media platform via content they create, no matter the extent of their advertising ability, which is where another wrinkle lies in the image of an influencer. For the sake of their own image, a brand is much more willing to partner with, say, someone whose content is modeling on Instagram, than someone whose content is primarily lip syncing explicit lyric riddled songs on Tik Tok, even if there’s a strong following for both among the youngest generations.

There is one last wrinkle in the way influencers have succeeded as a concept and helped shape the decade, and that is the common misconception that influencers don’t have any skills, so anyone can supposedly do what they’re doing. While the same argument can be used with celebrities too, at least most celebrities have a specific job other than just being a celebrity that is reflective of their talent (such as a singer or actor). In reality, while the luck it can take to make it as an influencer does play a role, there’s also a mix of charisma, marketing skill and a general ability to capture an audience, which not everyone has. This idea that to make it as an influencer might be as simple as making a certain type of content until it somehow gets popular inspires a lot of young people to try, which is part of why so many people who could be classified as influencers exist today. Very few will make it, but there’s a vision that it can be done because at the end of the day, the popularity of online content is dictated by the common people, as opposed to celebrities of the past whose popularity would be tied to the entertainment industry.

Because of the large variety of types of influencers, it’s no surprise that content itself has become more widely varied. The digital world has allowed pop culture itself to become more compartmentalized. Just a couple of decades ago, everyone could only watch the same hundreds of TV channels, listen to the same few radio stations and only be able to buy the music records that happened to be for sale. While we still have some of those relics of past pop culture, now there’re also millions of YouTube channels and millions of artists on platforms like Spotify and SoundCloud to choose from. And if that isn’t enough, there’s also the mainstream television and music of other parts of the world that the Internet allows us to see.

“There’s a lot more sort of facets of pop culture that someone can choose to immerse themselves in. They’re all connected, but you have all these options. You have all these genres of music accessible to everyone, there’s hip hop, there’s K-pop. You still have the whole American sitcom style TV, but you also have more and more anime. As the world is becoming more connected, pop culture is becoming more and more diversified,” Visweswaran adds.

While not all of the new content being put out will appeal to any one person, there’s so much that surely something is out there for everyone. However, consumers of entertainment might not always be looking for anything new. After all, it’s easier to consume something familiar than go out of one’s comfort zone to try something new. That’s why, as much as anything else, nostalgia culture has been a big part of the 2010s, as many of us opt to immerse ourselves with the pop culture of the past, or at least something resembling it.

“You notice trends, whether you’re a historian or just a person observing pop culture, of things that return or come back in style in these 10 or 20 year cycles whether it be music, fashion, literature, this sort of ebb and flow, back and forth… it’s fine, there’s nothing wrong with it, but it also reminds you that there’s sort of nothing new under the sun,” says Stanek.

Nostalgia culture’s rise can be attributed to the high concentration of content the digital age has provided us with, making us more likely to want to stick to familiar things, particularly from decades with a more universally well defined pop culture. And the entertainment industry has caught on, capitalizing on this to make content that remind their key demographics of a simpler time. Perhaps it’s no wonder that ‘80s and ‘90s nostalgia has been a big part of media during the 2010s, as people who came of age then now have more purchasing power than any demographic and kids of their own to expose to mass media.

“It’s a really good marketing strategy to say we’re gonna make this come out 20-30 years later when the people who saw this when they were kids are now in their 30s and 40s and having their own kids, and we’re just sort of gonna capitalize on that,” Stanek adds.

There’s an appeal in nostalgia based content for the people who grew up with the original type of content, the age demographic that it actually is nostalgia for, but it can be said that nostalgia based entertainment has stuck around because the younger demographics find something in it too. Even for those of us who grew up with the internet, all the content out there can be overwhelming, and for some, it’s easier to look back at what happened before our time and romanticize, though even this isn’t unique to the present day, and is more of a sociological phenomenon.

“Every teenager hates the era in which they live. Like, man, this prior era was great. Every society, every time period, has done that,” Stanek adds.

Knowing how we look back at, say, decades like the ‘80s and ‘90s today, it’s easy to predict that 30 years from now, we’ll be giving the 2010s the same nostalgic treatment. What aspects will be nostalgic for those of us who came of age in the 2010s, and what aspects will fade from our existence? Only the future can truly answer that, but it’s fun to think about what might lie ahead. What’s near certain is that social media will stick around and be remembered as having come of age in the 2010s.

As Visweswaran says, “Social media is definitely not going away. What we see with social media in the past with MySpace, and now kind of Facebook, the popular social media apps will change over time, like now Tik Tok’s getting popular. But the idea of general social media I don’t think is going away.”