Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

Evanston’s historical perpetuation of housing discrimination

January 28, 2022

Since its founding in 1863, Evanston has been perceived as an emblem of opportunity. From the town’s locational assets—Northwestern, Chicago and Lake Michigan—to its ambitious and business-oriented citizenry, Evanston has garnered a reputation for being one of the most productive towns in the nation.

At the core of Evanston is its neighborhoods: the life-blood of the city. Roots run deep here, and it’s obvious why. On almost every block, there appears to be an ivory-brick church enshrined in old-English handwriting or a house whose porch splinters at the base, a physical representation of its use over the decades. Neighborhoods are symbolic of a city’s history, and in Evanston, our neighborhoods are monoliths of a complicated past—one of segregation and progress, of inequity and enfranchisement.

When Evanston’s Black community began to emerge in the late 1880s, reaching a population of approximately 125 people, they lived amongst a relatively integrated society.

“Everyone lived everywhere [because] Evanston was very rural before 1900,” Dino Robinson, founder and executive director of Shorefront Legacy Center, an organization aiming to archive the Black history of Chicago’s North Shore, says.

As larger swaths of African Americans began to migrate into Evanston, things began to change.

“By 1900, there was a demarcation, where there was [an incentive] to push groups of people in certain areas of Evanston, the most visible group being the Black community,” Robinson shares.

As racist sentiment began to grow in Evanston, so did its population. The beginning of the 20th century marked a period in which increasingly high numbers of Americans switched from renting homes to owning them, and Evanston provided both the land to develop houses and the opportunities to be economically successful. For Black families in particular, home-ownership was a way to generate decades of wealth, making up for the potential wealth lost to chattel slavery.

“[There was an] extraordinary value for ownership of property. [It] was the root of power, and the absence of property was the root of disempowerment,” San Diego State University history professor Andrew Weiss says. “[Property was] rooted in the experience of former enslaved people in the South who [had been] prevented from gaining property,” Weiss continues. “[So] there was this long standing tradition in value for ownership that is rooted in Black communities, and that was [also] true in the urban North as well.”

As Weiss explains, homeownership was deeply valorized within the Black community, but in areas like the American South where lynchings and Jim Crow permeated Black welfare, it was almost impossible to own property and build financial prosperity. A culmination of these financial struggles for Black Southerners, in addition to the growing industrial opportunities of the North, generated one of the largest migration movements in the United States, known as the Great Migration.

“Approximately six million Black people moved from the American South to Northern, Midwestern and Western states [between] 1910 and 1970,” the National Archives wrote.

For those who moved North, many found themselves in major cities like Chicago, and eventually in its surrounding suburbs, particularly Evanston. Its opportunities and “safe haven” atmosphere blanketed Black families from the horrific violence they faced elsewhere in the country. Evanston wasn’t exempt from its own forms of discimination, however. Evanston was in the process of pushing certain groups, as Robinson describes, into specific areas, providing Black families opportunities to own homes but within strict geographic limits.

“Unlike many suburbs that sought to exclude African Americans altogether, leading members of Evanston’s real estate establishment played a role in the growth of Evanston’s African American community,” Weiss wrote in his 1999 dissertation titled Black Housing, White Finance.

Like Weiss theorized, Evanston differed from adjacent suburbs because the city already had a well-established Black community by the time the Great Migration began. Evanston wasn’t exclusive in the sense that the town refused to sell homes to Black buyers—in fact, real estate agents encouraged their ownership—but the city was exclusive about where Black families could live.

“Evanston’s white real estate brokers apparently developed a practice of informal racial zoning. In effect, they treated a section of west Evanston as open to African Americans, while excluding them from the rest of town,” Weiss wrote.

Confined to land between the sanitary canal and railroad tracks, clear geographic barriers limited Black suburbanization and integration into the rest of Evanston, and it appears this strategy of informal racial zoning was effective.

“Between 1910 and 1940, there was not a single area of African American expansion outside of west Evanston, in spite of Black population growth of almost 5,000,” Weiss reports.

In addition to real estate agents, Evanston’s white bankers, builders and residents played active roles in restricting Black expansion. For one, “banks generally refused to make mortgage loans to Black households seeking to buy homes on blocks that were not viewed as ‘acceptable’ for Black people,” Robinson says.

Additionally, Evanston builders could refuse to construct homes for Black homeowners in areas outside of west Evanston.

“Builders did not sell properties to Black households if the homes were outside the area set aside for Black people,” Weiss wrote. “Builders constructed more than 1,400 new homes in northwest Evanston during the 1920s and 1930s, none of which were sold to Black households.”

When bank and building discrimination weren’t effective enough in restricting Black settlement, whites mobilized together to establish neighborhood improvement associations. Ironically, these associations didn’t improve neighborhoods; they segregated them.

“South of Church Street and west of Asbury Avenue, white homeowners formed the West Side Improvement Association ‘to preserve [the neighborhood] as a place for white people to live.’ As part of the plan, they formed a syndicate to buy homes that were at risk of being sold to a Black family,” Robinson and Evanston History Center Director of Education Jenny Thomson wrote in a 2020 City of Evanston report titled Evanston Policies Directly Affecting the African-American Community.

The effect of these policies were stark.

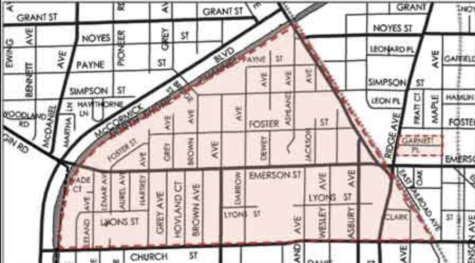

“By 1940, census data showed that 84% of Black households in Evanston lived in the triangular area. This area was highly segregated—95% Black.” (This is shown in image 1).

In the report, the “triangular area” demarcated a specific region where Blackness was present in Evanston. It was a section between the North Shore Channel (sanitary canal), East Railroad Ave. and Church Street. When intersected, the streets formed a triangle shape.

Evidence indicates that the 1940s marked a point where Evanston crystalized its segregated neighborhood dynamics. Amongst the discriminant involvement of realtors, banks, builders and citizens, the City of Evanston rolled out its most racially codified policy yet: redlining maps.

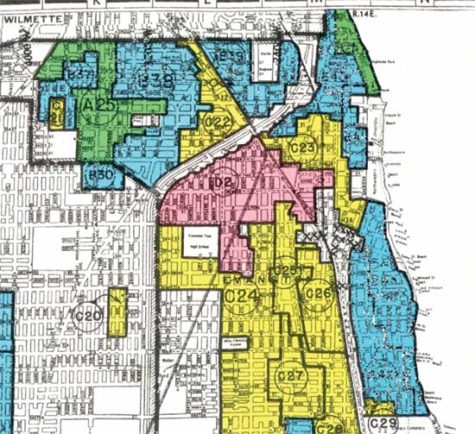

Following the economic short-falls and property foreclosures of the 1930s, largely due to the Great Depression, the federal government established the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (H.O.L.C.) to evaluate various American neighborhoods and their perceived level of financial lending risk. H.O.L.C. deployed federal examiners to “consult with local bank loan officers, city officials, appraisers, and realtors to create ‘Residential Security’ maps of [major cities],” writes the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. One of these cities was Evanston, who published its map in the 1940s.

“The advent of the redlining maps, the final, whole map [being published] in the ‘40s, basically codified where the Black community was supposed to live,” Robinson states. “[If you look] at all the redlining maps [published] across the country, all the red areas always said, ‘This area would be better if it wasn’t for the Negro population.’ So, that was consistent. You can see how that codified a Black community and [also] how to decimate that Black community, [which was always pushed into] a remote zone. It informs the funding there, it informs the real estate agent where to push Blacks and [also] where to push whites if they’re still there.”

Redlining maps served two purposes (refer to Image 2). For one, they identified specific neighborhoods as high or low risk for investment; to the right of all redlining maps was a key which presented four colors—green, blue, yellow and red—and each color’s corresponding information. All neighborhoods colored red were “high risk” and all neighborhoods colored green were “low risk.”

The second purpose of the maps: segregation. In the surge of suburbanization and ethnic growth in Evanston, agitated whites needed legal ways to prevent integration in their affluent neighborhoods. Redlining affirmed racist sentiments in Evanston by pushing Black residents into “high risk” red areas. When Black Evanstonians requested support, either for construction or loans, it was often limited because they lived in “high risk” zones.

What is particularly striking about Weiss’ findings are the hastened and seemingly conflicting actions of white Evanstonians. Evidently, vigilant racism plagued the brains of many, made visible by their discriminate actions in real estate, construction and private associations. However, they also contributed positively to Black welfare once barriers were placed between them that ensured a segregated city.

Mortgage lending was perhaps the most widely used practice amongst white elites. As Weiss wrote, “they lent money to Black home buyers, which gave them a financial stake in the Black neighborhoods in Evanston and expressed their faith that Black borrowers were a sound financial risk.”

In addition, whites participated in philanthropy, donating money to necessary material goods.

“During the 1910s and 1920s, white donors supported campaigns to establish a Black hospital, a boarding house for single Black women, day care services for Black children, and a YMCA to provide recreational facilities for Black youth,” Weiss wrote.

While both mortgage lending and donations helped strengthen Black welfare, it also exuded elements of white benevolence and supremacy. Whites felt that participating in charity made them exempt, either from the problems they created or from a solution to prevent potential conflict. Regardless of their intent, research indicates whites simultaneously uplifted and destroyed Evanston’s Black community.

One final question remains: why were whites so actively involved in Evanston’s Black housing market?

It appears, in the context of the Great Migration, whites were attempting to contain a movement they couldn’t stop. As Evanston’s population grew in diversity, discriminatory housing policy was seen as a remedy to control an emerging racialized population. As Cora Watson, former president of the North Shore Community House, explains, “Whites didn’t want the colored,” but “they couldn’t keep us from moving in.”

Quoted in Weiss’ dissertation, Caledonian Martin, a former resident who moved to Evanston in 1909, noted, “Evanston, the beginning of it, was for rich people to help and not for the colored to come out and live . . . but we get here, and we stay.”