Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

Evanstonians, ETHS community members reflect on opportunity gap, efforts to detrack at ETHS

January 28, 2022

Over the years, ETHS has been consistently scrutinized for its opportunity gap. However, it wasn’t until 2010 when action was taken to detrack select ETHS courses. Despite the process continuing today, much controversy remains.

Editor’s notes: Many of the conversations around race, as well as available student testing data, used in this piece were limited in nature. Oftentimes, Black students were referred to as the only minority group of note or all non-white students were grouped together. The Evanstonian acknowledges the absence of stories and data from other racial groups, groups that navigated the same rigid, white supremacist structures that are talked about in this piece but may have had different experiences than those depicted here.

In addition, within this article, the Evanstonian uses the term ‘opportunity gap’ to describe the disparity in academic outcomes across race and class rather than the ‘achievement gap,’ putting focus on the system rather than the individuals impacted. Still, some quotes may refer to the achievement gap.

‘First Class’: a community dedicated to academic excellence

Evanston Township High School and the City of Evanston are places where students and families expect a specific definition of excellence; a definition that demands academic success and is rooted in white supremacist and capitalistic ideals built to include some and exlude others. This expectation isn’t new, dating back to Northwestern University’s founding in 1851.

In 1982, the theme of ETHS’ yearbook, the Key, was “First-Class.” The senior class was taking pride in their high grades, AP classes, college scholarships and SAT scores.

“We want to continue the advance of civilization, so we tirelessly uphold the ‘First-Class’ principles nurtured during our years of high school education. We stand upon the threshold of a future that will most certainly be conceived in our image,” the Key staff wrote to introduce the theme that year.

When Nathaniel Ober became superintendent of ETHS in 1981, expectations were high. He entered as a decorated Harvard graduate and school administrator. While at Harvard, Ober studied under James B. Conant, Harvard’s president and a leader in pushing the model of large high schools across the country. Ober had spent much of his career working in public schools and performing various roles. The ETHS school board was impressed with Ober’s success in working at racially integrated schools and hired him in hopes that he would emphasize racial equity at ETHS.

“The community he came to houses a diversity of ethnic backgrounds, incomes, housing, and social patterns—one of the reasons people choose to live and raise their children in Evanston. It is also the reason for the school’s fine national reputation,” Liane Clorfine, a Chicago Tribune journalist, wrote in 1981.

ETHS was one of the first high schools in the country to pilot college-level Advanced Placement (AP) courses in 1955, and the school took great pride in its plethora of advanced classes during the early 1980s. This correlated with ETHS’ commitment to having a high rate of students attend college, which was already three in four graduates. To achieve this ‘fine national reputation,’ the school valued academic accomplishments above any other form of student achievement, a notion that was rooted in white supremacist ideology. ETHS used tools such as tracking to perpetuate this education method.

Tracking led to evident racial segregation among various levels of the same course. Specifically, higher-level courses were made up of predominantly white students. Since many Black and brown students started their high school career in lower-level courses due to systemic structures in place in elementary and middle schools, many were barred from higher-level courses that were part of the path towards “excellence.”

As community members began to challenge this discriminatory structure, people’s perspectives also fluctuated with regards to what “excellence” meant in a school setting. This resulted in a change towards the standards and tools that were utilized to achieve a ‘fine national standard.’ As the perspective on excellence shifted, ETHS followed suit and implemented many detracked classes in the 2010-2011 school year. While AP courses and Advanced Math curriculums remained, the goal of detracking was to give all students access to the best curriculum, rather than a curriculum that varied based on course level placement.

“There’s obviously a lot of reasons to be concerned about the way that tracking puts us at the risk of expanding the achievement gap,” Evanston Mayor Daniel Biss shares. “There are also certain challenges that come with detracking, and I’m glad that we have dedicated people who are deputized with the job of working through those difficult issues.”

Recent changes signify how the ETHS administration continues to redefine “excellence,” stepping away from the racist systems that the school relied on for years in pursuit of the term. However, ETHS’ journey towards understanding that its definition of “excellence” needed to evolve did not come without a fight.

A ‘tremendous’ divide: tracking exacerbates opportunity gap at ETHS

Stepping into the halls of Evanston Township High School circa 1992, one would find themselves briefly submerged in the high school’s forever-favorite advertisement: a “melting pot” of students, oozing at the brim with ethnic and racial diversity.

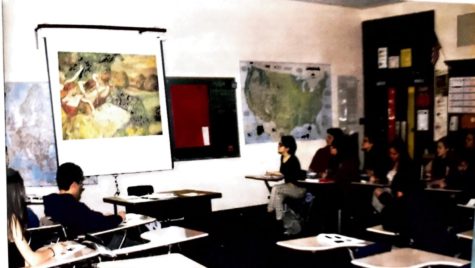

With a population made up of 46 percent white students, 44 percent Black students, six percent Hispanic students and four percent Asian students, one may claim this boast was justified. Besides the term’s tokenization and implications of assimilation, a peek within classroom doors quickly removed a spectator’s rose-tinted glasses.

At the time, ETHS classes were generally split into three levels in order of rigor: Level 1, Regular and Honors. Data about the racial makeup reveals a pattern. Regular algebra, for example, had a total enrollment of 98 Black students and 17 white students. Its honors level counterpart, on the other hand, included 12 Black students and 148 white students. English and U.S. history exhibited the same trend: Level 1 English had a 30:1 ratio of Black and white students, while honors had a 37:148 ratio. Level 1 U.S. history had a 61:3 ratio while honors had a 28:88 ratio.

Pam Cytrynbaum, class of ‘84, recalls a similar divide.

“It was tremendously segregated.”

One prominent reason behind this blatant segregation? Tracking.

Tracking refers to a system that separates students into classes of various rigors based on their perceived ability. Its origins in the United States can be traced back to the early 1900s as a response to the influx of immigrants. Elitist scholars claimed that many immigrant children’s only future lay in factory work, and, therefore, advanced classes should be created for those with a college-bound future. There were obvious xenophobic and racist undertones to these decisions, with the impact hitting close to home.

The late 1930s show ETHS’ first signs of tracking. Marie Claire Davis’ History of Evanston Township High School: First Seventy-Five Years, 1883-1958 illustrates how the system began.

“The faculty agreed that, whatever title they be given, these groups of students would exist—those intent on entering Eastern colleges; those concerned with general colleges, such as the state university; those in the practical arts; those in business; and ‘those who know not whence they go,’” Davis wrote.

The Great Depression is noted as one of the causes of this shifted mindset. It is also interesting to note that Evanston’s population nearly doubled between 1920 (37,234) and 1940 (65,389) according to the U.S. Census. Many students showed excitement over the new array of classes: nursing, hygiene and woodworking to name a few. While the change was welcomed, it set the unexpected foundation for a preemptively racist system.

Racist encounters inspire mobilization

As the only public high school in Evanston, ETHS welcomed all students in the community from its founding in 1883. Unfortunately, there are limited accounts of racialized experiences and statistics in the school until the 1960s.

In Mary Barr’s Friends disappear: The Battle for Racial Equality in Evanston, the current assistant professor of sociology at Kentucky State University illustrated her experience as a white woman growing up in the Evanston school system in the ‘60s. Barr’s account signals the evident racialized divide in the career-oriented courses introduced at ETHS 30 years prior.

“The white students typically took classes with an academic focus, while the Black kids took classes with a vocational focus.”

There is nothing wrong with striving for a future outside of academia. However, the education system evidently pushed, and pushes, one idea of “excellence,” which is receiving higher education and acquiring an “esteemed” career. There is a blatant pattern between which students are perceived as capable of achieving this definition of “excellence” (and given the opportunities to reach it) versus those who receive value and opportunity solely based on their capacity to join the working class and serve those that achieve “excellence.”

“The school model we use right now is an outdated one that goes back to the time of cutting industrialization where school systems were very quickly trying to figure out which students were going to work with their hands and which ones would work with their minds,” Bobby Burns, class of ‘04 and current Fifth Ward Alderman, explains.

As Barr and Burns suggest, in a tracked system, Black students are expected and pushed to work with their hands and white students with their minds. In our capitalistic, white supremacist society, one which requires a certain degree of education to know how to work the system and be respected, ETHS’ system of tracking made it clear who was set up for success and who was not.

In January of 1992, ETHS was struck by a racist incident involving a German teacher and two Black students that had a resounding effect on the conversation surrounding racism at ETHS and what role tracking played in the larger discussion.

Dr. Allan Alson, ETHS’ Assistant Superintendent for Curriculum and Instruction from ‘90-‘92, reflects on what he remembers of the incident. After hearing three Black male students cause a “loud commotion” outside his classroom after lunch, the German teacher shared some deeply racist, inflammatory comments with his class. From what Alson recalls, the teacher said something along the lines of “They ought to take those kids that do stuff like that and put them in the zoo.”

The incident rightfully caused outrage, and the administration was criticized for a delayed response; so much so that students walked out a few days later to demand faster, more concrete action.

The school organized six town meetings to discuss the incident. Over time, the discussion moved from this teacher’s racist remarks to a discussion of how tracking could be used as a salve towards larger racial injustices at the school if done correctly.

In an op-ed in the May 1992 issue of the Evanstonian, Matthew Price shared an opinion that represents the favored side of the conversation at these meetings

“The advantages [to mixed level classes] seem to be overwhelming because of mixed, diverse classes. Units like immigration, the history of racism/discrimination in America, the Civil War and Reconstruction, and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s would be greatly enriched.”

Yet, not everyone agreed. At the April 30 meeting, Northwestern University professor James Rosenbaum made inflammatory statements surrounding tracking at ETHS. That same May issue of the Evanstonian stated that the comments were “received as insults to the African American community and the lower class. Many felt that some of the criticisms were directed at Black parents.”

Unfortunately, “After much of the protest and commotion died down, it became apparent that there were many supporters of Rosenbaum in the crowd.” There was a resounding amount of work to be done.

Alson became the superintendent that fall of 1992. After observing the manifestation of racism in the high school, Alson knew his main focus in his new position with ETHS staff on his first day as superintendent.

“Our first goal,” he says, “was to strive for equity.”

While superintendent, a role he maintained until 2006, Alson implemented various foundations for both success and struggle in relation to the commonly-supported objective of equity.

One of his first actions was to implement a higher minimum GPA requirement for students to participate in extracurricular activities. Alson believed that was a crucial step to raise expectations for all students. Additionally, he created two programs that focused on supporting students of color and low-income students towards higher achievement: Advancement Via Individual Determination (AVID) and Steps Towards Academic Excellence (STAE). The former superintendent also founded the Minority Student Achievement Network (MSAN), which continues to connect students of color from across districts to form relationships that strengthen confidence. All three of these programs continue to run at ETHS today.

Alson also shares an unpublicized method his administration used to promote academic success for students of color.

“For U.S. History… what we did, which we didn’t really publicize, was a small set of us chose teachers. We knew that there were certain sets of teachers [in which] we believed, very strongly, [would cause] kids of color to have a greater opportunity to believe that they could succeed and ultimately to succeed academically. We made very conscious choices of placing students, and we did that by studying student failure rates.”

The former superintendent highlights an important aspect that plays into the academic success of students of color: whether the classroom is a safe environment to learn and grow in the first place. If a student doesn’t feel seen and respected by their teacher, there is an immediate hindrance towards learning that plays a role in the opportunity gap, also often referred to as the achievement gap. Alson continues to share that the teachers who did not fall into this “safe” criteria were placed in “professional development” that taught them about examining internal biases and building relationships with students.

Amidst controversy, tracked classes remain

Despite Alson’s best efforts, racism via tracking continued to prevail.

Lower expectations of academic success materialized through the same courses offered in varying degrees of rigor and “intelligence.” Eighth grade students would spend a Saturday in December completing the standardized EXPLORE test, which determined their freshman year class level.

“You might be put in honors, you might be put in mixed honors, you might be put in regular or you might be put in enriched—and enriched actually meant the lowest level,” Eric Witherspoon, current ETHS Superintendent, explains.

The EXPLORE test was a dated, long-standing tradition.

“I talked to a woman just recently—in fact, she was in the class of ‘64—and she remembers going and taking the EXPLORE test when she was in the eighth grade,” Witherspoon shares.

Current Assistant Superintendent of Curriculum and Instruction Dr. Pete Bavis summarized in a 2015 report, Detracked – and Going Strong, the way this system functioned before and during Alson’s superintendence.

“The designation of ‘honors’ didn’t even take into consideration how students actually performed in class,” Bavis wrote. “This approach resulted in a structural barrier to mobility, which all but excluded students in regular tracks from accessing the most rigorous curriculum throughout their high school careers.”

Once students were placed in a track their freshman year, it was nearly impossible to transition to a new one.

It is crucial to note the factors that affected, and continue to affect, students’ performance in the classroom and on standardized tests. Burns expands on some of the cultural and societal influences.

“In my experience, a lot of white, wealthier classmates had access to tutoring and other enrichment opportunities outside of the classroom. And it wasn’t difficult for them [to access them]. It was routine; it was automatic.”

This pattern is observed all across the country. Due to housing discrimination, limited access to education and jobs for older generations, generational trauma and countless additional factors created by a white supremacist system, many Black families, Indigenous families, and families of colors are trapped in difficult financial and cultural situations.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the median income of white (not Hispanic) households in 2019 was $77,007. This is followed by $56,814 for Hispanic (any race) households and $46,005 for Black households. Less money equates to lower access to expensive, external resources that help improve academic performance.

“And so the question is: [what happens to] people who don’t have [access to outside resources], and they have a teacher that doesn’t really expect much out of them?” Burns continues. “They may come from a single-parent household, a working class household where they don’t have a ton of time to help their child with their education, and then don’t have the same access to tutoring. How do we level the playing field?”

Alson clarifies that eighth-grade teacher recommendations initially played a role in placement, the goal being to humanize students beyond their ability to test-take. However, he admits they were forced to eliminate these recommendations due to teachers’ racial biases.

Another important factor that Burns highlights is how white families are more likely to know loopholes within the system that can, sometimes unfairly, boost their child’s access to “success.”

“[For some white families], even if their student isn’t excelling enough to justify their placement in an advanced classroom,” Burns says, “they’ll call the district and make sure that their student is in that class. And that’s something that happens behind the scenes that a lot of people may not know. That makes a big difference.”

Due to the aforementioned reasons, the courses students were placed in seemed to lose melanin the higher the level they were.

In an article for the Chicago Tribune, Nicole Summers, class of ‘04, illustrated the visceral visual difference.

“You can look in a room and know if it is an honors or regular class by the color of the students’ skin.”

Burns, also ‘04, describes the blatant difference in experiences based on which level someone was in.

“Some students are in classrooms where there’s a higher expectation, and there’s an accelerated curriculum, and there’s these higher rates,” Burns explains. “There’s a push for them to excel in their studies. Then, in other classes, there isn’t that same expectation.”

Marcus Campbell, current principal and assistant superintendent, as well as former ETHS English teacher from 2001-2011, shares his experience as a teacher dealing with expectations for lower course levels.

“I remember teaching the Odyssey in freshman humanities,” Campbell starts. He explains an interaction with a fellow teacher who urged him to assign an easier version of the book to his two-level (also known as the “regular” level, below the honors level) students. “It was this big orange book, like a bedtime story. And I was [thinking], ‘there’s no way I want to give my kids this book.’ I had a great relationship with my kids. I had expectations for my students. I knew that if I gave them something like that, it would be offensive to them,” Campbell continues. “First of all, I was like, ‘What? They can do this. It’s my responsibility to get them through this.’ I’m not going to say they can’t do it, because they can.”

Mariana Romano, who has taught English at ETHS since 2002, shared her observed impact of poor expectations for students in lower-level classrooms at a board meeting in 2010.

Romano, who also taught “sophomore two-levels” at the time, described a troubling experience.

“At one point during the Jane Eyre unit, one of my sophomores asked me, ‘Why are you making us read this? Don’t you know we’re the dumb kids?’ I was ill equipped to address the damage to those kids.” Romano continued to express that “These students suffered, and still do, with the idea that they are inferior learners, and that stereotype threat guides their behavior and performance.”

As more teachers began to support the elimination of the tracking system that caused their students to lack confidence, Witherspoon, as newly-appointed superintendent, also grappled with the seemingly hidden, deeply-rooted reality of racial inequity at ETHS.

“I started in July 2006. I’m getting [ready] to go to school. Come the end of August, [the] staff comes back, [the] students come back; I’m so excited. Like I am today, I’m in the hallways a lot. I’m seeing the rich racial diversity of the school, as well as cultural diversity—how different kids dress and [different] languages [are] spoken. I just love it,” Witherspoon describes.

“But almost immediately, I observed something I didn’t know about Evanston when I accepted the job, and that was that, when you got in the school, how racially segregated the classes were.”

The superintendent notes ETHS’ demographic diversity was an attraction that initially drew him to the school. However, Witherspoon recalls a sense of shock towards the evident segregation he saw daily within the school.

“I could remember that, [during] passing period, as it’s time for class to start and getting close to the time for the bell to ring, you could literally sit in the hall and watch a lot of racial segregation. There were rooms where almost only students of color were going in, and there were rooms where almost only white kids were going in. I really thought those days were over.”

Witherspoon recalls a heart-wrenching wake-up call that shifted the trajectory of his time at ETHS and echoes the reality that teachers already knew.

“I’ll never forget, one day, I went [into a classroom],” he starts. “I slipped into a desk, and there was just a really nice young man, one of our Black males, sitting at the desk next to me.” With a tight throat, Witherspoon continues. “He leaned over and he said to me, ‘This is the dummy class.’ My heart sank.”

Witherspoon notes that he counted “15 kids in the room, 14 of them were Black males and one was a Black female. I thought to myself, right then, ‘This is wrong.’”

That interaction caused Witherspoon to critically rethink the system that had racially separated students in the first place.

“First of all, [it’s wrong that] in the eighth grade, we determined you belong in a ‘dummy’ class. It’s also wrong that you’re going to class where you’re not going to get the same education as the other kids in the ninth grade or the 10th grade because they’re going to get a better course, and it’s wrong that you’re going to be held down so that you can never take what we often say might be among our best courses,” he expresses.

This strict tracking system was valued by many community members and seen as an indicator of competitive and desirable education. However, outsiders in support of this system seldom had the chance that Witherspoon, teachers and students had to observe the harmful, internal effects that tracking inflicted.

In fall of 2010, Witherspoon, alongside the school board, announced a new structure for the following school year and beyond that aimed to provide access for all students to partake in ETHS’ “best courses.” That structure was Earned Honors.

The first target was a beloved honors English course available at the time only to high-achieving incoming freshmen. Placement was determined by the EXPLORE test, and, unsurprisingly, the majority of the students placed were white.

Earned Honors, now known as Pathway to Honors, formatted classes in a way that allowed all students to learn the same curriculum and have the opportunity to earn honors credit through assessments or projects. While many viewed this as a creative approach to eliminating classroom and curriculum disparities across students, a large population also publicly opposed the notion.

On Nov. 29, 2010, ETHS hosted a public school board meeting regarding the possibility of implementing Pathway to Honors classes. Community members crowded into the ETHS auditorium to listen and speak at the meeting that lasted nearly three hours.

“There were so many people, we had to start holding our meetings in the auditorium with microphones in the aisles so people could speak,” Witherspoon shares. “We would sometimes have people lined up from the microphone on each aisle all the way to the back of the auditorium waiting to speak; almost all speakers were against it. We had a lot of comments made that were just absolutely shocking and showed some severe racial bias.”

A little over halfway through the Nov. 29 meeting, a white man wearing a red tie stood at “microphone two” and introduced himself as Henry Latimer, a father of an ETHS sophomore at the time.

“First, I would like to address why I think you’re hearing some objections. Many of us with children who have worked hard to get them into honors classes do look [at] the world and changes [that take place] with grave concern that our children will have to struggle mightily just to stay in place. Anything that may be perceived as endangering their opportunities is looked at as somewhat askance, no matter how noble the goal.”

Latimer darts his eyes from the stage in front of him to the paper in his hand, then continues. “I think that we can also all agree that diminishing the opportunities for those who do have them now isn’t going to lift up those who don’t.”

Campbell recalls harsh memories of opposing stances in board meetings that were often embedded in racist language and ideology.

“Those days were terrible … This one lady [was] yelling at one of my students at the time. She was a white woman, yelling at a Black girl, saying this is all about reparations. I had never seen that kind of racism before. I’m from the South Side. I had never seen a white person with such anger yell at a person of color until I got here. The blatant racism was just awful.”

Underlying racism also lined complaints about the program. A predominantly white group of parents shared concerns surrounding the cost of easier classes for their top performing students.

An Evanston RoundTable article summarizing the Nov. 29 meeting describes how “One parent asked whether transcripts would look different, and if this proposal ‘will hurt my child’s chances of getting into highly selective schools?’”

This fear, layered with individualism and racism, was quickly shut down by Witherspoon that night.

“‘That sorting and labeling is not working,” he declared at the meeting. “If it locks out students so that they can never experience this high-powered school,” he added, “then we’re not doing our job. We will finally be a school that does not put lids on its students.’”

Speakers stationed at microphones was only one force Witherspoon was working to combat. Criticism regarding detracking took many forms, many of which exhibited uncivil territory.

“I was getting threats. People were reading about it in other areas [and] sending anonymous letters or messages, literally threatening my wife,” Witherspoon recalls.

The restructuring also caught the eye of larger crowds. To Witherspoon’s surprise, the most prominent newspaper in the Chicagoland area was eager to share its opinion.

“On Sunday, I had to go to O’Hare [Airport. I was going] to fly down to Florida to be with my family for Christmas. I grabbed the newspaper, and we go to the airport, we checked in and then we went to the gate. I open up to the editorial of the Chicago Tribune on a Sunday and the headline says, ‘Honors? Horrors!’ The Chicago Tribune wrote an editorial on how misdirected I was. Those were interesting times.”

To this day, the article, published on Dec. 17, 2010, can still be found on the Chicago Tribune’s website. In a standalone paragraph, the article boasts, “We’re with the protesting parents on this one. This is a terrible idea.”

Despite the varying levels of objection, Pathway to Honors garnered a lot of support from the community.

Campbell shares how “There [were] a lot of parents who said this is exactly what we should be doing. You know, a lot of Black and white and Latinx parents who said, ‘Yeah, this is exactly what we should be doing.’”

Kimberly Frasiar, ETHS class of ‘89, was one of these parents sharing their support at the Nov. 29 meeting.

“I have no doubt that if I had been given the opportunity for mixed level classes, my opportunities in this building would have been different,” Frasiar described. “That is why I requested next level classes for my children. I commend Dr. Witherspoon on his recommendation that all students will be given equal opportunities here at ETHS.”

Wilma Turner, author of Everyday Racism in America and the Power of Forgiveness and an audience member who described being one of 13 Black students to integrate Charleston High School in Charleston, Mo. in 1962, illustrated at the meeting how impactful the school board’s step towards equity was to her.

“I wish someone in my high school years ago had cared enough to fight for me.”

Turner continued to draw connections between her experience at Charleston and then-present realities at ETHS and across the nation.

“The struggle over how to educate minority students is not much different than it was nearly 50 years ago, when I was a high school student. They just don’t call you names out loud and throw tomatoes at you anymore. They use tracking.”

Campbell continues to reflect on the program’s supporters. “There were a lot of co-conspirator allies who also stepped up and said, ‘This is what my experience has been.’ Students, former students, who all spoke up and said: ‘This is exactly what we should be doing.’”

In turn, despite receiving a petition signed by more than 300 “recognized community leaders” requesting to halt the path to detracking, the board unanimously passed the new structure.

Detracking begins to take effect

The detracking initiative was promising: early statistics were favorable and have only improved since. In 2017, Bavis reported that the class of 2015, the first freshman class to take Pathway to Honors classes, took the most AP classes out of any graduating class prior to them. Furthermore, this same group of students held the largest ACT score average in comparison with every previous year. Today, the ETHS website reads, “In recent years, more AP classes have been added, and the number of students of all races taking AP classes has grown by over 300%.”

However, as more students from diverse backgrounds gain access to advanced classes, ETHS continuously struggles to make these spaces, ones that have traditionally been dominated by white students, welcoming and safe for everyone. Burns speaks to one group he identifies with that has been historically discriminated against in classroom settings.

“I think teachers expect to have behavioral issues with young, Black male students in particular, so they over-police, in a sense. I remember growing up where everybody [would be] talking in the class, but with some teachers, I would get singled out for my behavior, and a white student or some other student wouldn’t,” Burns recalls. “I think, because our society over-criminalizes young Black men in particular, that also finds its way into the classroom. In the same way that we’re over-policed outside, we’re over-policed inside. There’s too much time spent trying to modify behavior instead of teaching Black, male students.”

Although ETHS looked much different when Burns was a student 18 years ago, the disproportionate student penalization on the basis of race he speaks of has seemingly remained intact. Current students have made similar observations, which limits the capability for success in a class, regardless of whether it’s tracked or not.

“What I’ve noticed is [that] the Black kids are more likely to even be sent to the dean’s office, so that’s the first step of the pyramid of the discipline system: the teachers sending the kids to the dean. Who are the [kids that] teachers [are] claiming are disrespectful? Who are [the kids that] the teachers [are] claiming are disruptive? Who are the kids that teachers are saying are problematic? These are kids of color,” current junior and ETHS Students Organized Against Racism (SOAR) member Phoenix Perlow-Anderson notes. “A lot of the time, there’s more to the story than just the kid being disrespectful.”

For over a decade, ETHS has persistently worked to minimize the opportunity gap through policy change, but the school has yet to make meaningful strides in terms of fixing the discrimination that exists within classroom culture.

“[Black students] have to be twice as good as [white students] in order to be recognized, and I’ve felt like that throughout my whole time at ETHS,” Perlow-Anderson shares. “I have to speak more eloquently, [and] I have to do better in my work just to have that recognition of my excellence. I have to try two times harder than the white students in my class.”

In 2011, nine students founded Team Access and Success in Advanced Placement (Team ASAP) as a way to seek out equity in AP and higher level classes. Since then, Team ASAP has only expanded and continues to offer various resources to students who are enrolled, or plan on enrolling, in AP classes.

“The purpose of Team ASAP is to break down the barrier of who is able to be an AP student versus who isn’t able. We discuss aspects such as learning disabilities and race and how those play into the divide in AP classrooms,” junior and Team ASAP board member Kyla Wellington explains. “Right now, the student leaders, including myself, are focusing on different approaches of how to motivate students of all backgrounds to feel welcomed to at least try out one AP class that ETHS provides.”

From restructuring curriculums to forming student clubs, ETHS has relentlessly reenvisioned the ways in which it considers equity and inclusion. Despite the significant accomplishments of the school over the past 12 years, there is still immense improvement that must be made, and that comes with recognition and accountability.

“I think historically, one of the greatest challenges is that an apology is to blame somebody else. It’s always easy for the high school to blame the middle school, for the middle school to blame the elementary school, for the elementary school to blame the parents. Ultimately, an effort to shift the responsibility away is an excuse not to solve the problem,” Biss expresses. “It’s really exciting to live in a time when educators, as well as administrators and community members, are starting to say, ‘You know what? We don’t get to just be sad about this and say it’s somebody else’s fault. We’re going to take ownership and do our best to address this.’”

This concept of accountability is one that many activists have centered in their work. According to Bobby Burns’ mother, Martha Burns, a previous school board member who advocated for equity in the school, accepting responsibility is vital to the growth of ETHS. As the oppurtunity gap persists, as students of color remain feeling unwelcome in their own school, and as teachers continue to send the same students to the dean’s office, it is crucial to acknowledge the lingering segregation and discrimination that strongly permeates the building in order to truly eliminate it for good.

Bobby Burns remembers his mother’s attitude surrounding ETHS, which still holds up today.

“What [my mother] was always trying to get Evanston to do better is to, as an institution, accept its own [responsibility and] to take accountability for the achievement gap.”

Both Burns and his mother believe that any influential person or organization must accept the role they play in prolonging discrimination.

“In the same way that [what] any good coach or leader would do is to say, ‘Even if some of this is outside of my control, as the leader of educating students in this district, we’re going to take all of the blame. We’re going to say it’s on us, as an institution, to make sure students are educated. Every student is educated no matter what neighborhood they live in, what their household income is and what supplemental enrichment programs they have access to outside of school. Regardless of all of that, we’re going to take accountability for students failing in our school system,’” Burns describes. “She always wanted to push Evanston to do that, and I think [Evanston schools are] doing it now or certainly moving closer to it.”

Pathway to paradox: how high achievements led to segregated courses

Like many schools across the country, ETHS offers a wide variety of classes with a wide range of levels. With over 3,000 students in attendance each year and a student body that comes from a diverse variety of backgrounds, classes are divided into different levels, some deemed higher and more advanced than others. What do these different levels of classes mean to the students and the culture that they create at ETHS?

In 1982, ETHS began teaching an honors-level class that focused on looking at history through the eyes of morality and revealing parts of history like genocide, violence against Native Americans and Japanese internment camps in WWII, which weren’t usually thoroughly discussed in U.S. and World history classes. The class was only offered at an honors level. At the end of the year, ETHS used testing to show that the students in honor-level history classes, like this one, were less prejudiced than regular-level students. They also said that the women in these classes had a higher self-image than women in the regular leveled classes.

This class, like many other aspects about ETHS at this time, served as a symbol of the paradox that has existed at ETHS for decades. In many ways, its hard-hitting curriculum put the school ahead of its times. Students were being exposed to challenging and essential topics and discussions. However, at the same time, a divide between honors students and other students at the school, in terms of the level of education accessible to them—and even self-esteem—became more prevalent.

In 1983, the Chicago Tribune published an article entitled “Black students fall far behind whites, Evanston study finds.” At the time, Black students made up only 13 percent of honors leveled classes and 7.4 percent of Advanced Placement classes.

“Black kids get tracked into lower-level classes as freshmen and have a hard time getting out,” ETHS parent Donald Heyrman said in the 1983 article.

Additionally, Black students were three times more likely to fail a class and half as likely to receive an A or B compared to white students.

Heyrman later went on to say, “Differences in economics, family support for education, and family differences between Black and whites” were partly responsible for these drastic differences in performance and placement between students.

These factors, combined with the difference in accessibility and level of education received in honors and regularly leveled classes created a culture of extreme segregation.

“It was even more segregated than you even think it would be. I mean, it’s almost impossible to describe how segregated it was, and it was how the system was supposed to work. It wasn’t just segregated by race but also class. You have to understand the role that money and access play in that kind of thing,” Cytrynbaum explains.

However, this was a stark contrast to the school-wide academic reports ETHS was releasing. In 1987, the American College Testing (ACT) exam showed that ETHS students scored an average of 20.5, which was higher than the statewide average of 19.1. Additionally, in 1986, ETHS was the third-highest scoring school on Advanced Placement tests out of the entire Midwest region.

At this time, AP classes were beginning to become more prevalent, not just at ETHS, but on a national level. James A. Garfield High school in Los Angeles, which was reported by the Washington Post in 1987 to be full of gangs and violence,” began introducing more AP classes throughout the school. Only 15 percent of its students were enrolled in AP classes, but, by the end of the year, their test scores, overall student performance and even attendance increased. James A. Garfield High School was used as a national example of how AP classes, which offered students the chance to receive college credit, were a necessary factor in motivating students. This became nationally agreed upon by most administrators and teachers, and any worries about student stress levels regarding AP classes and the lack of diversity within them were quickly pushed aside as more test scores across the country increased.

This trend was seen particularly at ETHS. In the same year that James A. Garfield High School was recognized for its introduction of AP classes and the dramatically positive effect they had on their community, ETHS was ranked number five in the country for its AP Calculus program. In 1987, in just the math department alone, they administered 114 AP tests, a significantly higher number than most schools at the time.

By continuing to expand the ways in which ETHS implemented AP and higher level courses, the school directly advanced racial segregation that continued into the ’90s. In 1991, Black students made up 42.4 percent of ETHS’ total student population and white students made up 48.9 percent, but this racial balance was not reflected in the classrooms.

In an article printed by the Chicago Tribune in 1991, District 202’s Dean of Students at the time, Eddie Stevens, said, “The students in honors courses are mostly white, while those in remedial courses are mostly Black. The problem is that Evanston has the same problem that others have. We track students. In that type of system, the rich get richer.”

This tracking is seen even outside of AP and honors classes. ETHS has also offered multiple levels throughout all its curriculums, including varying levels of math. The accelerated math track, which is a prominent feature of ETHS’ math program, begins in elementary schools. Students who qualified for the accelerated math track would “skip a grade” of math, meaning they would learn the content of math classes that were intended for one grade above them. Much like how high school students experienced difficulty straying away from their freshman year tracks, fifth graders not placed in advanced math endured similar challenges.

“[Math tracks are] determined in middle school, so it’s pretty set by the time you get to ETHS,” ETHS Math Department chair Dale Leibforth explains. “[Accelerated math is] determined in fifth grade, so on that track, it is almost guaranteed you will take two years of AP math.”

Evanston/Skokie D65 middle and elementary schools started accelerated math in the late 1960s, after pushes from surrounding states. Historically, students in fifth grade were asked to take a math placement test that would determine their class placement for the remainder of their middle school and high school math career.

“We were testing every single fifth grader,” District 65 Director of STEM David Wartowski says. “Every single fifth grader, not only did they take the standardized [math] test, but we also had them take a written test, which was really difficult intentionally. Very few kids were meant to actually do what was on that test, and there were some unintended consequences of that. When we were writing the tests, and I saw a fifth grader’s answers [where] the student wrote nothing but ‘I don’t know. I’m stupid,’ [it was so difficult]. I can tell you firsthand, I witnessed many tears from students who were just feeling like they were not good enough.”

This system was damaging to the confidence of impressionable elementary students who did not qualify for the accelerated math program, despite these students being in the vast majority.

“Historically less than 1% of students in our district skip a grade of math. While the decision to skip is based on a battery of tests, our data indicate that students who skip typically post MAP scores at the 99th percentile several times in a row,” the District 65 website reads.

MAP stands for the Measures of Academic Progress, which was a series of testing administered to D65 students from second to eighth grade. Although MAP testing did not influence a student’s qualification for accelerated math, the students who were placed in the accelerated track typically performed well on these tests. With accelerated math being accessible to only a small portion of students, it noticably creates harmful, discriminatory trends.

“[The accelerated program] has historically not been very open to all students,” says Leibforth. “It tends to be very white. I think some of the changes [being made now] are trying to get how we can make it more equitable. It’s not as diverse as we want it to be, yet.”

To tackle some of the segregation that occurs within these accelerated courses, D65 terminated the fifth grade testing that determined the placement of accelerated tracks and stemmed insecurities in students from an early age.

“For purposes of placement, every single child is taking the grade-level math,” Wartowski explains.

ETHS is also taking a more inclusive approach to restructuring their math department and is promising new Pathway to Honors classes in order to help all students succeed at the highest possible level. Leibforth describes that going into the 2022-2023 school year, 2 Algebra and Pre-Calculus, classes that had previously been split by honors and regular, will be offered as Pathway to Honors classes.

“Now, [all students are] going to be together instead of having one [honors] group of students be successful,” Leibforth explains. “[All students] have a better opportunity because they’re getting exposed to the more challenging work on the [new] pathway than they were before.”

As administrators continue to strive for equity in all higher level classes, they remind themselves of the importance of opening classrooms to every student. Although their work to accomplish this has come with obstacles, Witherspoon shares that every student has benefited as a result.

“We are better off today than we were [before detracking]. I believe that just being in classes together [helps]. Once you get into [an untracked system], you might have more white kids in one class or more kids of color in another, because of their interests in the course, but not because they’re locked out of a course,” he explains. “I believe, no matter what grade you get in that class, you will benefit for a lifetime by being in a class with multiple perspectives.”

Michael Kruse • Feb 6, 2022 at 2:57 pm

Hello Evanstonian Journalists,

As an ETHS Alum and also a former teacher of one of you (:)), I just wanna say that this is an incredible piece of work. The number of threads you pulled together coherently, the deep primary sourcing of Evanston and ETHS histories (BTW I remember Pam Cytrynbaum the year behind me, though she won’t remember me– she was onstage a lot, while I was not), the frank and well-supported analyses and reflections on various initiatives and events, the excellent writing, all of which also point towards what must be a truly collabortive journalistic and writing environment. Nice work, nice indeed.

Thanks for writing the piece

mike kruse