Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Nashville in November 2025, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

When Foster School oepned, it featured an all-white student body. Over the next half century, the demographics shifted entirely, with the school featuring an all-Black student population by the 1950s.

‘It was a pillar’: Examining legacy of Evanston’s former Fifth Ward school

January 28, 2022

Evanstonians remember Foster School, a site of communal strength, and later, desegregation hardships has recently become a focus for discussions regarding race relations in Evanston.

‘An ethnic white community’: Foster School opens its doors

Foster School, located at 2010 Dewey Avenue, was the pulse of Evanston’s Fifth Ward for much of the 20th century, only for it to be closed as a neighborhood attendance school in 1967 and closed entirely in 1979.

Opening in 1905, Foster School was located on the corner of Dewey Avenue and Foster Street, in the heart of Evanston’s Fifth Ward. The school’s first principal was Ellen Foster, a female trailblazer in many aspects of Evanston’s history. Foster’s platform as principal revolved around questioning segregation, and she even ran for a superintendent position in 1918.

At the time of Foster School’s establishment, the school’s population was predominantly white with a heavily white staff. While there were just under 800 Black Evanston residents, they lived throughout the city and did not heavily populate the Fifth Ward until the 1930s.

“The Fifth Ward as we know it today was not the Fifth Ward then,” Dino Robinson, founder and executive director of Shorefront Legacy Center, an organization aiming to archive the Black history of Chicago’s North Shore, says. “The Fifth Ward was predominantly an ethnic white community.”

In 1908, when the school’s permanent building was constructed, the school housed mostly white children. In 1928 and 1932, additions to the original building were added to house a larger number of students.

When Foster School was created, other children in Evanston attended a variety of other public schools, many of which are still around today.

‘Citizens were stirred to action’: Segregation’s impact on the Black community

Throughout Foster School’s first years, Evanston schools as a whole began to face issues of overcrowding as the city’s population grew. To combat this emerging issue, which was only stratified by growing racial tension and separation, in 1918, 42 Black students were moved from other neighborhood schools to Foster School. This decision was met with severe pushback from many Evanston families of both white and Black children, mirroring protests that were happening simultaneously regarding other political topics, such as housing discrimination.

In an article published in the Chicago Defender, a Chicago-based Black newspaper from 1918, titled “Transfer of Pupils Causes Vigorous Protest in Evanston,” the movement of these 42 students caused protest and indignation within the Evanston community.

Additionally, the article stated that “Citizens were stirred to action when Thomas Elliot, president of the Fifth Ward Improvement Association, declared that the move of these pupils was unnecessary and that such a move by the school authorities warranted the attention of the residents of Evanston and a thorough investigation.”

In the years following the transfer of these 42 students and the subsequent protests, Foster School and Evanston’s Fifth Ward became progressively more Black, with demographics changing rapidly as a result of Jim Crow laws and redlining. As Evanston’s government began to implement laws in accordance with Jim Crow, common areas such as beaches and parks were segregated.

Many realtors also perpetuated redlining in Evanston, a racist practice in which mortgages are strategically offered to prospective homeowners to maintain predominantly Black and white neighborhoods. Through redlining, the Black community of Evanston was pushed into Evanston’s Fifth Ward, while many other areas of Evanston remained heavily white and more affluent.

One of the direct results of redlining in Evanston was a heightened level of segregation in the city’s public schools. As the Fifth Ward began to house a more significant Black population, the Black population at Foster School also began to rise. By 1930, Foster School’s student body was almost completely Black, despite employing no Black staff members.

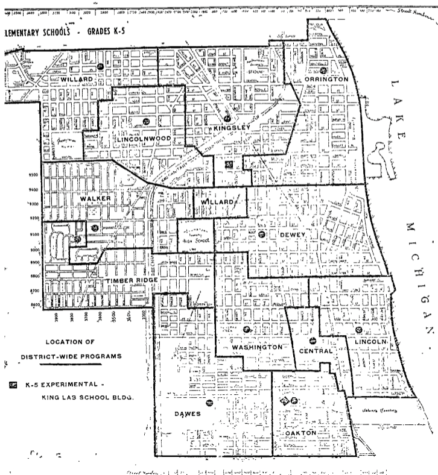

As explained in an Evanston RoundTable article, Foster School was also kept almost completely Black as a result of the City of Evanston’s efforts to redistrict when deemed necessary, in addition to redlining. For example, in a case where some Black families would move into a predominantly white neighborhood, the Evanston government would frequently redraw district lines so that the Black families were zoned for Foster School, despite their neighbors attending a different Evanston school.

While Foster School was becoming increasingly populated by Black families in Evanston as a result of the city government’s actions, other Evanston schools were actually seeing the opposite effect, also as a result of redlining.

Because redlining established such a deep racial divide in Evanston, other wards also saw a decline in racial diversity. With less racial diversity in each ward, neighborhood schools became more heavily segregated.

Despite the makeup of Foster School’s student body featuring few non-Black students, the first Black teacher, Patsie Sloan, was not hired until 1945. From there, other teachers of color began to be employed, especially throughout the 1950s. Additionally, Foster School boasted a tight-knit community and a solid educational experience.

“I liked going to school, I liked my teachers [and] I liked my friends,” former Foster School student Jo-Ann Cromer says. “I liked the fun I was having.”

‘We were well educated’: students, staff reflect on Foster School impact

To add a layer of complexity to the changing demographics of Foster School, Brown v. Board of Education (1954) reignited past conversations about what it would mean to desegregate Evanston schools. Because Brown v. Board of Education ruled that segregation was unconstitutional, Evanstonians began to wonder when the school board and superintendent would respond to these changes, with some arguing that issues of overcrowding in Evanston schools only exacerbated the need to desegregate. While Evanston’s desegregation tactics ultimately resulted in the bussing of Fifth Ward students to other schools, there was no further plan implemented for another decade.

While conversations regarding a push to desegregate Evanston schools occurred in the 1950s post Brown v. Board of Education and grew louder into the mid-’60s, Foster School had become a vibrant, thriving community within the Fifth Ward.

“The teachers were no-nonsense. Their whole reason for being there and being teachers was that you have to learn,” Cromer says. “The teachers there were Black and most of the students were Black, and I think they mainly wanted to make sure that we were well educated.”

In 1955, as the War on Poverty was becoming increasingly popular, Foster School housed a seven-week program aimed at supporting impoverished children living in the district. The program, called “Operation Head Start,” received nearly $25,000 in federal funding. This program, aside from supporting impoverished families, was designed to ensure that Fifth Ward students did not begin their schooling at a disadvantage, a phenomenon that frequently plagued low-income families. There were certain criteria to qualify for the program, such as a yearly income of less than $3,000. Students who qualified would enter Foster School prior to starting kindergarten and gain skills and support necessary to succeed once they began elementary school.

On March 12, 1957, a panel discussion by the Foster School PTA consisted of five men examining the techniques of education and what best benefits children within Foster School.

At the time, this panel was designed to aid the needs of Black Foster students specifically and continue to develop a progressive, effective educational model. Yet, by the early 1960s, the children whose best interests were being served were white students, with Black students being unnecessarily bussed out of their communities to ease potential inconveniences for white families.

Before the tumult of the late ‘50s and ‘60s for Foster School, it was a key feature of the Fifth Ward, shaping the children who grew up there. A Chicago Tribune article published in June of 1955 covers the retirement of Foster School teacher and Haven Middle School principal Helen Sanford. Sanford worked as a Foster School teacher for nine years before becoming the principal of Haven Middle School and later the principal of Dewey for seven years. During her 44-year tenure in schools, Sanford would often direct playground activities. Sanford’s impact on Foster School students was profound, and she felt strongly that Foster School students had a bright future.

“The children of today are much like those of my earlier teaching career—knowing all the charms and mischiefs—though I do believe they are less biased,” Sanford stated in the same Chicago Tribune article. “They are not prejudiced about race, color, religious, economic, and family backgrounds of their fellows.”

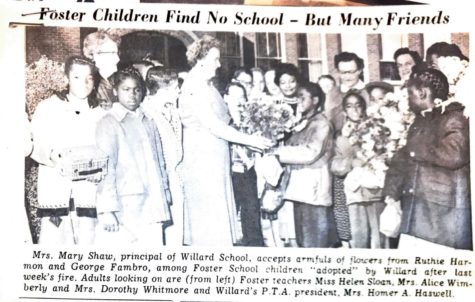

Unimaginable loss: The fire that devastated Foster School

In late October of 1958, Foster School suffered an unimaginable loss: a fire demolished the original part of the school building, causing the entire roof to collapse and damaging the newer wings that had been built in 1928 and 1932. There was an estimated number of $500,000 in damages.

At the time of the fire, Evanston City Manager Bert Johnson told the Chicago Tribune that the incident was being investigated, as there were concerns of potential arson. However, these claims remain unfounded. At the time, the fire drew an estimated 1500 spectators, according to the Chicago Tribune. The flames rose higher than 200 feet in the air and were visible for many miles.

Most importantly, the Foster School fire devastated the community of Fifth Ward, especially the residents that attended Foster School. While school was canceled the day following the fire, students returned to the Foster Community Building for some sense of normalcy just two days later. The Foster Community Building was right across the street from Foster School. However, the fire altered the breakdown of the Fifth Ward dramatically and ultimately primed the school for closure just a few decades later.

“They still talk about it today, and the Black community in the Fifth Ward especially [does]. [They] wanted [Foster School] back in their community so their children [weren’t] the ones bused,” Cromer said.

A few weeks after the fire, Dr. Oscar M. Chute, District 65 Superintendent at the time, announced a plan for the continuity of Foster School students’ education. In his outlined plan, kindergarten students would attend school in the St. Andrew’s Episopal Church, just a block away from Foster School. First, second and third-grade students would remain in the Foster Community Building, across the street from the school, until one of the new wings in Foster School reopened, which was estimated to take a month. The fourth-grade classes were transferred to Noyes Elementary School, which is now known as the Noyes Cultural Arts Center. The fifth-grade classes were moved to Willard Elementary School, and sixth-grade students were dispersed among the three Evanston middle schools—Haven, Nichols and Skiles.

This dispersal of Fifth Ward students across the rest of the city was a sign of things to come in the following decade.

After the fire, the part of the building that was demolished was rebuilt and students returned to the building and stayed there for the next decade until its closure.

At this point in history, Evanston was at a fascinating crossroads. Despite the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, Evanston had only just begun to discuss what it would mean to desegregate and integrate schools. However, in many ways, the fire that destroyed much of Foster School served as an impetus for desegregation in Evanston.

Seven years later, to deal with the growing unrest around Evanston’s lack of integration, recently-hired District 65 Superintendent Gregory Coffin assembled the Citizen Advisory Committee on Integration in September of 1965 with the goal of creating a reassignment plan for Evanston students. Coffin, who was hired to tackle desegregation in Evanston, later came under scrutiny for the ways in which he restructured the school system in the mid-1960s and the ways in which his actions ultimately left a large sector of the Black community without a neighborhood school.

“We’re not trying to just eliminate de facto segregation in the all-Negro Foster School or the 65-percent Negro Dewey school,” Coffin said in a radio interview from 1967. “We want to integrate all the schools, and this will do in September, where the range will be from 17 percent to 25 percent Negro. There’ll be this range of Negro student population in every school. And many of these schools, of course, have never had a Negro student in them.”

In May of 1966, the Chicago Tribune published an article documenting the frustrations that parents and guardians of children who attended Foster School felt at the lack of integration within the school. The article stated that many white parents supported the proposed plan to bus white students into Foster School and that Foster School parents threatened to picket the school if it was not integrated by the following fall.

A month later, the idea of turning Foster School into a laboratory kindergarten program was proposed to the District 65 school board with Coffin asking white parents to consider enrolling their incoming kindergarten students. The plan was received well by Evanston families and was ultimately approved a few months later, changing Foster School as the Evanston community knew it.

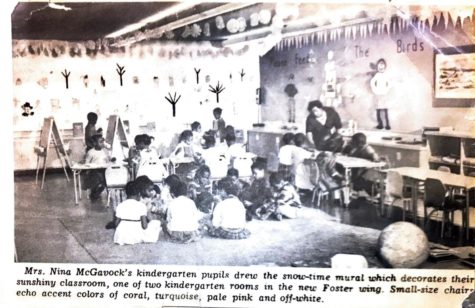

In August 1966, the D65 School Board approved this plan to implement a laboratory kindergarten in Foster School, stating that all older students would be bussed to the 15 other Evanston schools. The laboratory kindergarten was a part of Coffin’s efforts to eliminate de facto segregation in Evanston; the program emphasized higher level learning, creativity, reading and functioned with the intention of integrating classes.

Additionally, as outlined in Coffin’s plan and by the Citizen Advisory Committee on Integration, the experimental lab kindergarten would be voluntary and aimed to attract white families to the Fifth Ward. Families who enrolled their children and did not reside in the Fifth Ward were transported by bus to the Foster School building.

On Sept. 19, 1966, Foster School was formally integrated, with 139 white students attending the laboratory kindergarten program. Additionally, there were two Black students from outside Foster School district lines enrolled and 101 students enrolled who lived within Foster School borders and had previously attended Foster School.

Throughout the 1966-1967 school year, discussions continued to occur about the full integration of Evanston schools, the state of Foster School and how best to serve the children of Evanston. Given the success of the experimental lab kindergarten program at Foster School, discussions of turning Foster School into a complete laboratory school turned to action in 1967, effectively eliminating the Fifth Ward school that had been a core component of the community for decades.

Ultimately, the complete laboratory school that took the place of Foster School became known as Dr. Martin King Luther Jr. Laboratory School, despite being housed in the original Foster School building. It was not until 1979 that the lab school was moved to the former Skiles Middle School building, leaving the Foster School building abandoned until it was later purchased by Family Focus.

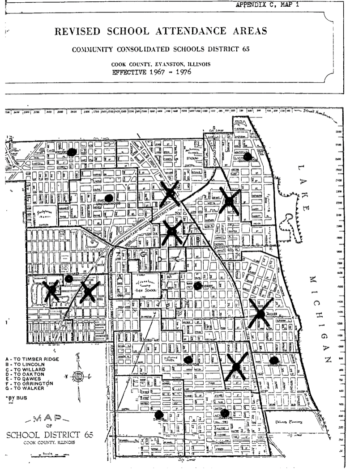

Additionally, in November of 1966, the Citizen Advisory Committee on Integration, formed by Coffin, brought the topic of desegregation to a vote at a school board meeting. The plan passed and was to be implemented in the fall of 1967, stating that each Evanston school was to include somewhere between a 17 and 25 percent Black population. While this new quota served its purpose, which was to desegregate Evanston schools, it had the complex effects of distributing students and breaking up the Fifth Ward community.

There were some parents who were grateful to have their children attending integrated schools, but others who felt that this seemingly simple change split the Fifth Ward community and broke up relationships between students and teachers that had been formed in Foster School previously.

“The optics of that, when the students are arriving at school, is [that the] Black kids are waiting on a bus to get them there,” Robinson says. “There’s no bonds they’re going to be creating in that classroom and after school activities might be limited because of that.”

‘A Negative Attitude’: Desegregation harms Fifth Ward residents

With Foster School set to establish a kindergarten center in the fall of 1966, one of the main goals was to adapt a program that would entice white parents through curating curriculum centered around students’ needs. Because no students were assigned to the Foster School laboratory kindergarten, administrators needed to ensure white families would apply. Specialists in industrial arts, art, creative dramatics and music were hired to plan and carry out the program. By December, the school board had partnered with the Northwestern University’s School of Education to create this experimental lab school.

In 1967, the West-Central area of Evanston was the first in District 65 to lose a local attendance center—the all-Black Foster School. Instead, the school became Evanston’s new integrated magnet school for elementary schoolers from across the city. By January, the experimental education program in Foster School was created. The implementation of this lab school came with many adjustments, which included providing consultants for program improvement, setting up local, regional and national conferences and workshops as well as assistance with publishing information about the new programs.

The lab school’s kindergarten was open to the entire school district and was aimed at desegregating through drawing in white students. The program received over 900 applications for attendance to the school.

In fact, families across Evanston were trying to get their children enrolled in what would come to be known as one of the most successful innovations in American education. Had the school been located in another ward within the district, it likely would not have been as heavily funded because these funds furthered integration goals.

In May 1967, the Chicago Tribune published an article covering the impact that grants, such as the Summer Institute for Integration, had on the new lab school, known as Martin Luther King Jr. Laboratory School. With the new multicultural environment of this lab school, the Summer Institute for Integration provided educators with a training program, emphasizing the education problems with race and new techniques to use in classes, counseling and parental communication.

Students were given specialized opportunities and educational aids in their classrooms such as projectors, tape recorders, TV equipment and slide viewers. What began as an all-Black population at Foster School before the change to becoming a lab school transitioned into a 25 percent Black population. Of the 650 students that ended up getting enrolled in the magnet school, 75 percent of them were white.

“Foster School really stands out, because it shows how the city segregated itself and then tried to manage the desegregation process,” Robinson says. “So when the City of Evanston was looking at desegregating the school system, it was kind of using Foster School as the model for that, but not [by saying], ‘let’s diversify communities,’ which is really the way to do it, but [instead by saying], ‘let’s bus students in. Let’s make an experimental school and bus white students in, displacing Black students so they had to be bussed elsewhere, so that we have an integrated model of just one school.’”

With these plans of segregation came a new bussing plan that reassigned the schools that Black children attended. Up to 450 Black children were bussed to other schools under this plan, across the seven catchment areas in Evanston. These children were transferred in order to racially balance the schools— to meet the stated goal of having 17 percent to 25 percent of each school’s student body be Black.

The plan to desegregate Evanston schools came with pushback. The community was deeply divided over the District 65 superintendency of Gregory Coffin, who was committed to desegregating Evanston schools. In the April 1970 school board election, with Coffin’s position on the line based on who was on the school board, the anti-Coffin candidates won. The board voted not to renew Coffin’s contract, and he was removed as superintendent on April 17 of that year. However, the integration plan was still set to continue, with Joseph E. Hill becoming the new superintendent after serving as interim superintendent.

An article published in the Evanston Roundtable in 2019, titled “Foster School: Its Role in Desegregating School District 65 in 1967 and Its Closing in 1979,” found that student enrollment within Evanston was swiftly dropping and overtime transitioned from 10,860 students in 1967 to 8,413 in 1976 and to 7,061 by 1979. By September 1976, College Hill, Miller and Noyes Schools were shut down due to the decrease in enrollment. This prompted District 65 to establish a new plan for its schools.

According to an Evanston Review article published in December 1979 covering the change in Evanston schools over the decade, in November 1978, Hill and the D65 administrators declared a plan to cut $2.4 million from the 1979-1980 school year district budget. This plan also included closing five schools in the next two years, and, by early 1979, the board voted to close Kingsley, Timber Ridge Central and King Lab schools and transfer the King Lab program to join an existing program at Skiles Middle School.

When Hill analyzed the possibility of reopening the King Lab (Foster) building as an attendance school on Jan. 30, 1979, his original plan had been to transform the King Lab experimental program into Skiles Middle School, while the empty school building would become an expanded administration building.

But this proposal would have restructured the Black and white students’ bussing program. If Foster School would have been reopened, more students would have needed to be bussed, and consequently, two more school buses would have needed to be utilized. Instead, Hill suggested transforming the preschool program from Miller School to King Lab. Yet again, the Black community was not happy with this idea, due to the risk that Foster School would return to being an all-Black school, especially with programs like Head Start and Family Focus already serving as all-Black programs within the Fifth ward.

Finally, a 5-2 vote on Feb. 5, 1979 led Foster School to no longer be an attendance area school, with the Foster School building being sold to Family Focus. Although there was much debate over the closing of Foster School, the school board’s decision came down to the fact that Foster’s reopening would affect the neighborhood schools. Due to its size and location, the board would have had to consider school closings like Dewey, Willard or Orrington schools—schools in predominantly white areas.

On Feb. 8, 1979, the Evanston Review published an article documenting the importance of reopening Foster School within the community. With the decline in revenues and enrollments and neighborhood schools closing down as a result, Evanston school communities came out in favor of keeping Foster School and reopening it as a regular attendance school.

Many Black residents in Evanston stated that bussing to meet federally mandated racial guidelines had always been a one-way street. Leaders in the Black community claimed it was time for white residents to experience the burden of racial abuse.

Bennett Johnson, a member of the Coalition of Dignity in Education and Evanston NAACP education chair-man, was an advocate for reopening Foster and said in the Evanston Review, “Bussing Black children out of the Foster area to desegregate other Evanston schools has created negative attitudes among Black kids.”

On March 15, 1979, the Evanston Human Relations Commision (HRC) held a public hearing to give community groups and individuals a chance to express concern regarding the plan of Foster School closing. A large concern was the racial inequity of bussing between white and Black students. The committee argued that the plan ignored the current unequal distribution of minority and Black students, and that the plan was not equitable to Black students.

A Black student was four times as likely to be distance bussed to school as a non-Black child. And although Black children made up only one-third of the K-5 school population, over two-thirds of all the distance-bussed children were Black. This was the burden of no longer having a neighborhood school in the Fifth Ward.

According to a Human Relation Commission report from 1979, “A serious shortcoming of the Boards data on the ‘distance busing’ is that the term is used to describe two very different sorts of bussing: 1) transporting children who live too far away from their nearest school; and 2) transporting children to a not-nearest school in order to achieve racial balance.”

Although the board had agreed to equalize the burden of new bussing, 60 more Black children and 34 non-Black children would be distance bussed in the following 1979-80 school year.

Johnson, in a statement on behalf of the district-wide parent committee to the EHC, said, “The proposed plan will increase the burden of bussing on the Black children of this city.”

Another concern was the separation of community that the school board decision created. Foster School had become a symbol of continuity for Evanston’s Black community. Its history of being an all-Black school and its use as a social and recreational space left Black residents frustrated and in fear of losing the community it had built. After becoming a magnet school in 1967, Foster School had been used for community-wide benefit. Now, a keystone to community integrity was also being stripped away.

Superintendent Joseph E. Hill, who had attended Foster School and later returned as a teacher and administrator during the early stages of Evanston’s desegregation era, said if the building were to go unused, “There’s a fear it will slowly but surely turn into something that will be degenerating to the community, not only as an eyesore but as a source of a lot of problems.”

Another issue addressed in the statement was the expected discharge of over 140 teachers under the school board’s decision. 1967 was the first year that the district had operated with a focus on hiring Black teachers and ensuring Black educators had the chance to become administrators and principals. But the school board’s decision to shut down Foster school failed to address this issue, leaving them lost on how to proceed.

Despite these efforts and issues, on March 19, 1979, the School Board voted to approve the new school attendance map which re-drew the school attendance boundary. This effectively distributed students from the Fifth Ward across seven attendance areas, which they would then be bussed to every day. The fact that this approval came prior to when the projected bussing figures had been prepared indicated how little care the district showed towards the implications this would have on the Black community.

“I think Evanston dropped the ball, and when I say Evanston, I mean the Evanston school system and all the roles that play within that, to reimagine how they looked at neighborhoods, housing and resources,” Robinson says.

With Skiles Middle School closing in the spring of 1979, the school board decided that King Lab was to be moved into the Skiles building as a complete magnet school. This move is how the Fifth Ward of Evanston wound up with no school at all.

When Foster School closed, both Black and white students were transferred to different schools for the 1979-80 school year. According to data provided by the district, 96 Black students and 321 non-Black students were bussed to King Lab in 1979-80.

‘Foster School was a pillar’: honoring the legacy of Foster School

Closely following the closure of Foster School and the move of Martin Luther King Jr. Laboratory School into the Second Ward, families throughout Evanston had different reactions to the educational changes.

“I do not question that every one of you on the Board have acted professionally, sincerely and out of deep concern for the educational systems of District 65,” Klaus Mueller wrote in a letter to the school board in 1979.

Even with the support from some families, others were hesitant to applaud the board, more focused on the difficult changes that their students would be facing in the coming years as other schools around Evanston closed. Some parents from Kingsley and Foster filed a lawsuit in 1979 against District 65, claiming that the closure of Foster School constituted as racial segregation.

The closure of Foster School left an empty building in the Fifth Ward, also leaving behind a major community focal point.

In July 1979, the Evanston Review published an article explaining how the Foster School’s ad hoc committee created a questionnaire, which was mailed to 2,000 Foster School community residents, seeking ideas for use of the Foster School building. These ideas stretched from creating a trade school for skills like carpentry, plumbing or mechanics to a high school diploma center, an alternative elementary program center to a recreation center and even a roller skating rink or west branch of the Evanston Public Library.

While ideas for what to do with the space were numerous, for over a decade, the former school building stood empty until Family Focus Evanston bought the building in 1987.

“Foster School was a pillar in the Black community. It was the only school that the people in the Fifth Ward went to. It was very important to the parents and the teachers,” Cromer says.

When Family Focus officially bought the former school building in 1987 from D65 after first moving to the Fifth Ward in 1983, the community organization began to transform the space into one that would serve Evanston residents and connect citizens in the Fifth Ward. Prior to its closure, Foster School served as the neighborhood attendance school for residents of the Fifth Ward, connecting students, parents, guardians and teachers. The school had created a space for community building in addition to education, a space that disappeared from the heart of the Fifth Ward after its closure.

“The transformation of the shuttered school building into a vibrant community center serving Evanston’s youth was a testament to ‘what can happen when people in the community pull together,” Bernice Weissbourd, former president of Family Focus, said in a 1987 edition of the Evanston Review.

The purchasing of the former school building by Family Focus began to rebuild community connections in the Fifth Ward. The nonprofit organization was started to support child development and other social services. After taking up residence in the Fifth Ward, Family Focus initiated programming to provide after-school care, family advocacy and other services to Evanston residents.

While the organization has called the Fifth Ward home for over 40 years, Family Focus decided to begin the process of selling the building in 2017. Throughout the process, the directors of Family Focus made it clear that the organization was not leaving Evanston; rather they were only moving to a new location and would continue to provide services to Evanston residents. However, the announcement of this move sparked controversy among residents, many of whom had acclimated to the presence of Family Focus in their neighborhood and were upset by its decision to relocate.

Library

An article published in the Daily Northwestern in 2019, titled “Up for sale, Family Focus commits to maintaining presence in Evanston,” highlighted the various concerns of Fifth Ward residents over the intended move. Many of these worries were centered around the loss of another community center, mirroring some concerns brought up by the closure of Foster School.

Throughout the process of trying to sell the building, residents of the Fifth Ward and other community members advocated for the building to remain within the community. Their advocacy led to the formation of a group called Foster Center Our Place, an organization that would fill the community center role in the Fifth Ward that Family Focus was leaving behind.

After a drawn-out search, Family Focus decided to remain in the former school building, a positive choice which helped to ease some of the concerns voiced by residents. Rather than taking over, the people who created Foster Center Our Place volunteered to help maintain the services and outreach that Family Focus provides, continuing to branch out into the Evanston and Fifth Ward communities. The joint effort from both community organizations led to a renaming of Family Focus, now called Family Focus-Our Place.

Throughout the years since the closure of Foster School, proposals have been brought to the District 65 school board for the creation of a new Fifth Ward elementary school.

The creation of a Fifth Ward school would enable students who live in the Fifth Ward to have a neighborhood school that they can walk to rather than having to be bussed to another elementary school, which has been the case for Fifth Ward students since 1967.

The push for this Fifth Ward school has been a major topic of discussion in Evanston for years. Over the years, there have been numerous attempts to build a neighborhood school in the Fifth Ward to replace Foster School, which at a school board meeting in 2011 came close to being passed. Two of the voting members voted against its creation, effectively silencing the proposal.

“Experience across the country does show that it’s going to be a difficult task to ensure success for all of these kids. Our administration shows annually that we have made good progress on academic achievement, both improving performance of kids and narrowing the achievement gap between white children and our Latino and African American children,” Richard Rykhus, a former District 65 School Board member, explained in an article from the Evanston RoundTable.

Ultimately, Rykhus voted to align with the effort to close the opportunity gap instead of the risk that would come with opening a new school.

“Could Evanston rise to the challenge to ensure success at the new school? It is certainly possible. For me, given the improvements we have seen in academic performance and the factors that I have described, it’s not a risk I’m willing to take,” Rykhus elaborated.

The most recent proposal for a school occured in 2012 when there was a referendum on the ballot aimed at putting $45 million towards building a Fifth Ward school. Based on planning that District 65’s New School Referendum Committee Meeting had done heading into the 2012 referendum, the plan was for students to be pulled out of the Orrington, Kingsley, Lincolnwood, Willard and Dewey catchments.

“Advocates of the new school envisioned a community hub in the Fifth Ward, where students could walk to school and parents could be more involved in their children’s education. Some said it would finally right a wrong caused in the late 1960s when African-Americans in the ward were bused to schools elsewhere in the name of integration,” read a 2012 Chicago Tribune article.

While many Evanston families were in favor of the referendum, 54 percent of Evanston voters ended up voting against it, causing the push to open a Fifth Ward school to fail yet again.

Robinson argued that the very people that provided the diversity would be the ones hurt by the failure of the proposal.

“[But] those same families who [provided diversity] to those schools had been disenfranchised, or their voices always have been muted. So this was an opportunity to do something when there was a benefit to a community, and the amount of money to produce that school would be much more affordable than what it is now,” Robinson says.

In the aftermath of the failed proposal in 2012, Evanston residents and advocates for a Fifth Ward school began to conceptualize different ways to achieve their goal of centralizing access to education for students who live in the Fifth Ward. Through these discussions, a proposal to create a STEM school was raised.

The idea behind the STEM school proposal came following a school board discussion to convert Bessie Rhodes into a Spanish-English immersion school. One of the parents who spoke in opposition of this decision proposed creating a magnet school located in the Fifth Ward instead.

In the proposal to the school board, the STEM school was framed as an open enrollment opportunity, although preference would be given to students who live in the Fifth Ward in an attempt to provide those students with closer access to a school.

As the idea for a STEM school garnered more awareness, parents and interested parties began to collect emails of other interested people. Part of their work included conducting a study with Northwestern University to gauge interest about the creation of the school.

“That study was intended to hear from Black Evanstonians across the whole city, not just the Fifth Ward,” Henry Wilkins, a STEM school advocate, says. “It’s not just about returning a school to the Fifth Ward, it’s about [asking], ‘What are some of the things that the Black community is saying about education?’”

The study done by Northwestern was the result of a grant awarded to a group to survey and amplify Black voices in Evanston in an attempt to fully capture the different perspectives on education.

Proponents of the STEM school argue that although the school’s attendance would be choice-based, allowing students from every part of Evanston to attend, priority would be given to students in the Fifth Ward. This idea fits with the fight to bring back a school to fill the gap that Foster School’s closure left.

“There’s a lot of people that say they want a school to return [to the Fifth Ward]. But there’s a faction of folks that don’t want to see a school return because they’re concerned about gentrification and their taxes going up,” Wilkins explained. “The reason why we think a magnet model makes the most sense is you can prioritize folks that live in the Fifth Ward and make sure that every person that wants to go to this school is guaranteed a seat. And then, make it open to all of Evanston.”

The proposal for a STEM school in the Fifth Ward has not yet been passed by the school board. However, the support from residents and parents has not wavered.

“I think our vision is a winning vision that brings people together. We were very intentional with how we navigate our messaging and our vision to make it more encompassing,” Wilkins explains.

The push to open a Fifth Ward school has cultivated many opinions. While a vast majority of the Evanston community believes the push to open the STEM school is a good idea, others have their concerns about opening the school—increased property taxes being one, with the optics of diversity being the more covert concern underneath.

“Money would be put on the forefront as the reason why,” District 65 superintendent Devon Horton says. “But if you get behind the dollar sign, there are other issues. There are individuals who feel diversity is what makes Evanston great. But I would challenge many and say it’s not the diversity that makes it great alone. It’s the belonging. Students feeling like they belong and being connected is what could make this city even greater.”

White people who voted against the school proposal ignored the positive intentions and impacts of having a Fifth Ward school for the Black community.

“I think people can’t stomach the thought of: here is a brand new school, state of the art school, where the student body is predominantly Black,” Robinson says.

Those defending the Fifth Ward’s legacy are continuing to make improvements to the plan that would call for a well-rounded and diverse school.

Alongside the advocacy to create a new school in the Fifth Ward, efforts have been made throughout departments of the city to honor the historic school. In 2018, a panel of citizens began the process of reviewing the building for a historical landmark designation.

Throughout the tedious process, citizens have advocated in support of the former school building, citing the immeasurable impact the school and Family Focus have had on Evanston and the Fifth Ward community.

Library

Recently, former Fifth Ward alderwoman Robin Rue Simmons spoke in favor of the historical designation in an article published in Evanston Now, explaining the impact that Foster School and Family Focus had on her relationship with the Fifth Ward as a child.

“[The building has been] a resource and place of refuge and empowerment and encouragement in the community,” Simmons said.

In addition to the efforts on the part of the city to preserve the memory of Foster School, other residents have stepped in to highlight the importance of the former school and how it shaped education in Evanston.

In an effort to remember Foster School and honor its legacy, a play entitled “Concerning Foster” was created by Mudlark Theater in January 2020. The play follows Foster School students through the process of desegregating Evanston schools, as well as through the Foster School fire and even into present-day diversity, equity and inclusion conversations happening in Evanston schools.

“We landed on wanting to praise Foster for what it was but also acknowledge the inherent problems that come in having an underfunded, segregated school. [We wanted to celebrate] the fact that it was a place where young Black kids could be around people that look like them, and how, when that’s taken away from you, it really does affect your sense of self,” Kenya Ann Hall, one of the playwrights of “Concerning Foster,” says.

The show served as a look into the influence that Foster School had on its students and future students in Evanston.

“We wanted to show the arc, because oftentimes, when we think of school segregation, we think of it as so long ago, when it’s really not,” Hall says.

“People are alive who went to that school as children. We definitely wanted to highlight Foster [School] as it was, because a lot of people don’t remember it, and the people deserve to see it as a functioning educational institution.”

Char • Dec 6, 2022 at 8:13 am

True journalist approach. Very informative