Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

Unimaginable loss: The fire that devastated Foster School

January 28, 2022

In late October of 1958, Foster School suffered an unimaginable loss: a fire demolished the original part of the school building, causing the entire roof to collapse and damaging the newer wings that had been built in 1928 and 1932. There was an estimated number of $500,000 in damages.

At the time of the fire, Evanston City Manager Bert Johnson told the Chicago Tribune that the incident was being investigated, as there were concerns of potential arson. However, these claims remain unfounded. At the time, the fire drew an estimated 1500 spectators, according to the Chicago Tribune. The flames rose higher than 200 feet in the air and were visible for many miles.

Most importantly, the Foster School fire devastated the community of Fifth Ward, especially the residents that attended Foster School. While school was canceled the day following the fire, students returned to the Foster Community Building for some sense of normalcy just two days later. The Foster Community Building was right across the street from Foster School. However, the fire altered the breakdown of the Fifth Ward dramatically and ultimately primed the school for closure just a few decades later.

“They still talk about it today, and the Black community in the Fifth Ward especially [does]. [They] wanted [Foster School] back in their community so their children [weren’t] the ones bused,” Cromer said.

A few weeks after the fire, Dr. Oscar M. Chute, District 65 Superintendent at the time, announced a plan for the continuity of Foster School students’ education. In his outlined plan, kindergarten students would attend school in the St. Andrew’s Episopal Church, just a block away from Foster School. First, second and third-grade students would remain in the Foster Community Building, across the street from the school, until one of the new wings in Foster School reopened, which was estimated to take a month. The fourth-grade classes were transferred to Noyes Elementary School, which is now known as the Noyes Cultural Arts Center. The fifth-grade classes were moved to Willard Elementary School, and sixth-grade students were dispersed among the three Evanston middle schools—Haven, Nichols and Skiles.

This dispersal of Fifth Ward students across the rest of the city was a sign of things to come in the following decade.

After the fire, the part of the building that was demolished was rebuilt and students returned to the building and stayed there for the next decade until its closure.

At this point in history, Evanston was at a fascinating crossroads. Despite the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, Evanston had only just begun to discuss what it would mean to desegregate and integrate schools. However, in many ways, the fire that destroyed much of Foster School served as an impetus for desegregation in Evanston.

Seven years later, to deal with the growing unrest around Evanston’s lack of integration, recently-hired District 65 Superintendent Gregory Coffin assembled the Citizen Advisory Committee on Integration in September of 1965 with the goal of creating a reassignment plan for Evanston students. Coffin, who was hired to tackle desegregation in Evanston, later came under scrutiny for the ways in which he restructured the school system in the mid-1960s and the ways in which his actions ultimately left a large sector of the Black community without a neighborhood school.

“We’re not trying to just eliminate de facto segregation in the all-Negro Foster School or the 65-percent Negro Dewey school,” Coffin said in a radio interview from 1967. “We want to integrate all the schools, and this will do in September, where the range will be from 17 percent to 25 percent Negro. There’ll be this range of Negro student population in every school. And many of these schools, of course, have never had a Negro student in them.”

In May of 1966, the Chicago Tribune published an article documenting the frustrations that parents and guardians of children who attended Foster School felt at the lack of integration within the school. The article stated that many white parents supported the proposed plan to bus white students into Foster School and that Foster School parents threatened to picket the school if it was not integrated by the following fall.

A month later, the idea of turning Foster School into a laboratory kindergarten program was proposed to the District 65 school board with Coffin asking white parents to consider enrolling their incoming kindergarten students. The plan was received well by Evanston families and was ultimately approved a few months later, changing Foster School as the Evanston community knew it.

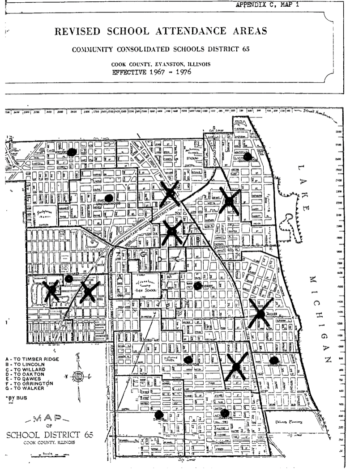

In August 1966, the D65 School Board approved this plan to implement a laboratory kindergarten in Foster School, stating that all older students would be bussed to the 15 other Evanston schools. The laboratory kindergarten was a part of Coffin’s efforts to eliminate de facto segregation in Evanston; the program emphasized higher level learning, creativity, reading and functioned with the intention of integrating classes.

Additionally, as outlined in Coffin’s plan and by the Citizen Advisory Committee on Integration, the experimental lab kindergarten would be voluntary and aimed to attract white families to the Fifth Ward. Families who enrolled their children and did not reside in the Fifth Ward were transported by bus to the Foster School building.

On Sept. 19, 1966, Foster School was formally integrated, with 139 white students attending the laboratory kindergarten program. Additionally, there were two Black students from outside Foster School district lines enrolled and 101 students enrolled who lived within Foster School borders and had previously attended Foster School.

Throughout the 1966-1967 school year, discussions continued to occur about the full integration of Evanston schools, the state of Foster School and how best to serve the children of Evanston. Given the success of the experimental lab kindergarten program at Foster School, discussions of turning Foster School into a complete laboratory school turned to action in 1967, effectively eliminating the Fifth Ward school that had been a core component of the community for decades.

Ultimately, the complete laboratory school that took the place of Foster School became known as Dr. Martin King Luther Jr. Laboratory School, despite being housed in the original Foster School building. It was not until 1979 that the lab school was moved to the former Skiles Middle School building, leaving the Foster School building abandoned until it was later purchased by Family Focus.

Additionally, in November of 1966, the Citizen Advisory Committee on Integration, formed by Coffin, brought the topic of desegregation to a vote at a school board meeting. The plan passed and was to be implemented in the fall of 1967, stating that each Evanston school was to include somewhere between a 17 and 25 percent Black population. While this new quota served its purpose, which was to desegregate Evanston schools, it had the complex effects of distributing students and breaking up the Fifth Ward community.

There were some parents who were grateful to have their children attending integrated schools, but others who felt that this seemingly simple change split the Fifth Ward community and broke up relationships between students and teachers that had been formed in Foster School previously.

“The optics of that, when the students are arriving at school, is [that the] Black kids are waiting on a bus to get them there,” Robinson says. “There’s no bonds they’re going to be creating in that classroom and after school activities might be limited because of that.”