Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

‘We were well educated’: students, staff reflect on Foster School impact

January 28, 2022

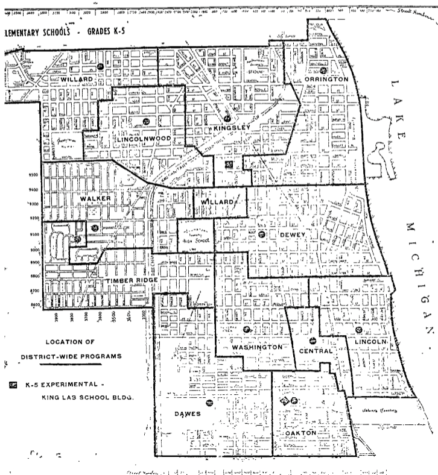

To add a layer of complexity to the changing demographics of Foster School, Brown v. Board of Education (1954) reignited past conversations about what it would mean to desegregate Evanston schools. Because Brown v. Board of Education ruled that segregation was unconstitutional, Evanstonians began to wonder when the school board and superintendent would respond to these changes, with some arguing that issues of overcrowding in Evanston schools only exacerbated the need to desegregate. While Evanston’s desegregation tactics ultimately resulted in the bussing of Fifth Ward students to other schools, there was no further plan implemented for another decade.

While conversations regarding a push to desegregate Evanston schools occurred in the 1950s post Brown v. Board of Education and grew louder into the mid-’60s, Foster School had become a vibrant, thriving community within the Fifth Ward.

“The teachers were no-nonsense. Their whole reason for being there and being teachers was that you have to learn,” Cromer says. “The teachers there were Black and most of the students were Black, and I think they mainly wanted to make sure that we were well educated.”

In 1955, as the War on Poverty was becoming increasingly popular, Foster School housed a seven-week program aimed at supporting impoverished children living in the district. The program, called “Operation Head Start,” received nearly $25,000 in federal funding. This program, aside from supporting impoverished families, was designed to ensure that Fifth Ward students did not begin their schooling at a disadvantage, a phenomenon that frequently plagued low-income families. There were certain criteria to qualify for the program, such as a yearly income of less than $3,000. Students who qualified would enter Foster School prior to starting kindergarten and gain skills and support necessary to succeed once they began elementary school.

On March 12, 1957, a panel discussion by the Foster School PTA consisted of five men examining the techniques of education and what best benefits children within Foster School.

At the time, this panel was designed to aid the needs of Black Foster students specifically and continue to develop a progressive, effective educational model. Yet, by the early 1960s, the children whose best interests were being served were white students, with Black students being unnecessarily bussed out of their communities to ease potential inconveniences for white families.

Before the tumult of the late ‘50s and ‘60s for Foster School, it was a key feature of the Fifth Ward, shaping the children who grew up there. A Chicago Tribune article published in June of 1955 covers the retirement of Foster School teacher and Haven Middle School principal Helen Sanford. Sanford worked as a Foster School teacher for nine years before becoming the principal of Haven Middle School and later the principal of Dewey for seven years. During her 44-year tenure in schools, Sanford would often direct playground activities. Sanford’s impact on Foster School students was profound, and she felt strongly that Foster School students had a bright future.

“The children of today are much like those of my earlier teaching career—knowing all the charms and mischiefs—though I do believe they are less biased,” Sanford stated in the same Chicago Tribune article. “They are not prejudiced about race, color, religious, economic, and family backgrounds of their fellows.”