Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Nashville in November 2025, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

‘We got to do something:’ Evanston’s history with gun violence spikes

Forty years since handgun ordinance, Evanston still seeks solutions to gun violence amid recent rise in incidents

December 16, 2022

Content warning: This article contains references to gun violence and its after effects.

A 13-year-old Bulls fan is preparing for the next school day at Haven Middle School. It’s a Thursday, and he only has a week left before graduation and then his birthday. He’s an eighth grader, so he’ll be moving on to Evanston Township High School next school year. It should have been one of the happiest weeks for him all year. His family had just set up a motion detector light outside of his Aunt’s house. The boy steps outside a side door to test the new feature. He is struck by a stray bullet. The child runs back inside the house and tells his Aunt that he has been shot before immediately collapsing to the floor. The boy’s name is Wayne Hoffman, and he died in Evanston on June 6, 1997 at 12:50 a.m.

Evanston is a community grappling with gun violence. It was then, and it is today. The events of last year’s lockdown at ETHS, and other situations involving guns—from the killing of Devin McGregor, an Evanston elementary school student, and the shooting at the McDonald’s on Dempster Street, to a gun being found on a student inside the school last month have contributed to a growing awareness of how guns are currently impacting Evanston.

At ETHS, there have been a number of policies, both implemented and pondered, that aim to combat the issue of school safety head on, with the school putting into place new safety procedures to more accurately know who is in the building at all times as well as considering the implementation of metal detectors or other alert detection systems. To understand where the fear of guns comes from and why the Evanston area has been struggling with it, we must look back forty years, to when the Evanston City Council passed its first ordinance banning handguns.

***

Forty years ago, on Sept. 13, 1982, the City Council passed an ordinance banning handguns in the city limits. The ban was in place to limit violent crime in the city of Evanston. It was enforced lightly, with a limited number of police officers imposing the will of that particular law.

Evanston was, at the time, the largest city to ban handgun possession. The law prohibited possession of handguns within city limits. Before this law was passed, 10 percent of Evanston residents owned a handgun, compared to 15 percent nationwide. And yet, the ordinance did not have a discernible impact. Evanston had a 24 percent drop in armed robberies in the following years, versus 21 percent across the U.S. That three percent was a difference of six robberies, going from 193 to 187.

When the handgun ordinance was put into place, Evanston was already a safe city, with five percent fewer guns than the national average. There was only so much the ordinance could do, especially because it was lightly enforced. Only 74 violations of the law occurred from 1983-1985.

Evanston was a safe city then, and compared to the rest of the country, it still is today. The most recent FBI crime rate statistics are from 2019, when Evanston had a total of 115 violent crimes. During 2020, the city had a total of 130 violent crimes. This means that for every 606 people in Evanston, one was a victim of a violent crime. Not only is this almost half of the armed robberies alone from 1983, but it is also lower than the country-wide average. Just as crime has dramatically decreased since it peaked nation-wide in the 1990s, the same is true in Evanston. Still, COVID-19 had a dramatic effect on the nation, and one way its impact has been felt is through an increase in crime following decades of decreases. There has been an increase in gun violence since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, nationally and in Evanston, as well. While Evanston was a safe place in 1982 when the City Council passed a handgun ordinance, so is it today. Yet, there have been a number of gun-related incidents in the last 13-months that have led Evanstonians to another period of fear across the community with regards to guns.

***

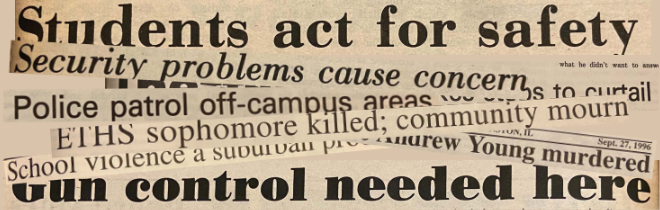

In the city of Evanston, gun violence has come in waves. One of the waves of violence is from the mid to late 1990s, when two teenage students and one ETHS graduate were shot and killed on separate occasions in Evanston. All three of the murders could be connected to gang violence.

The first of the incidents came on June 11, 1996, when 1995 graduate Andrew Young was shot and killed while he waited at a stoplight at Howard and Clark Streets in Chicago. Young was a speed skater who had trained with gold medalist Dan Jansen. After 10 years of training, he decided to call it quits so he could attend DeVry Technical Institute. He was slated to start school there in the fall of the year he died.

Gunman Mario Ramos had graduated from ETHS two days before. His accomplice, Roberto Lazcalo, was fifteen at the time of the shooting. Ramos and Lazcalo came to the stoplight on a motorcycle where Young was waiting in a car. Ramos walked to the driver’s side and fired off several shots. According to an old Evanstonian article, witnesses claim that Lazcalo flashed a gang sign as Young was shot. Young was not known to have had any involvement in gangs, but it appears he was the target of one anyway.

It was only a few months later on Dec. 12, 1996, when fifteen-year-old sophomore student Ronald Walker II was murdered as he left a grocery store near ETHS. He was shot twice with a handgun, once in the forehead and once in the left ear. Walker died almost instantly. According to former Evanston Police Lt. Charles Wernick in a news conference,

“There was no confrontation. In our estimation, it was nothing short of an execution,” he said.

Almost a year later, it was uncovered by the Evanston Police Department that Walker had been shot by Frank Drew, an Evanston resident, and Jeffrey Lurry. The two gunmen claimed to have shot Walker because they mistakenly believed he was a member of a rival gang. Drew and Lurry were walking in the territory of a rival gang, dressed in all black. After seeing Walker, they approached him after he exited a corner grocery store. Both Drew and Lurry fled on foot after the killing, believing there would be retribution for their actions from either a gang or the police.

The death shocked everyone in Evanston. It sparked anti-violence and anti-gang marches throughout the city. Sherry Walker, Ronald’s mother, was distraught during a news conference.

“I always wanted to be to this point where I could be a little at peace. I’m not totally at peace, because my son is gone; he’s never coming back,” she said at a news conference close to a year after the shooting.

The next incident came on June 5, 1997, the day that Hoffman was shot. The thirteen-year-old eighth grader who went to Haven Middle School was only a week away from graduating and moving on to ETHS when he was the tragic victim of a sniper attack and shot in the back in the middle of his shoulder blade.

The murder was not intentional. Hoffman was shot by a stray bullet that was meant for a gang gathered on the front porch of his Aunt’s home. The shooters, Jeffrey Williams and Larry Cox, had several altercations earlier in the day leading up to the final confrontation with the group. Hoffman was not part of any of the arguments.

“It is indescribable,” said Cmdr. Michael Gresham, former head of the Evanston Police Department’s investigative services division in an Evanston Review article. “I just hate to use the ‘wrong place, wrong time’ [phrase], but he took what somebody shot at somebody else.”

Many in the community were shocked by the murders. It almost felt as though they were random, like the flu. Swift and painful. three past, present and future ETHS students had been killed at a young age, without the city being able to see what people they would turn out to be.

Young’s twin brother Sam, who was in the passenger’s seat during the shooting, described the moment after the shot was fired.

“Drew just faded. I watched his spirit leave.”

The same could be said of Hoffman, Walker and many other gun violence victims.

***

When researching spikes in gun violence over the years, one of the questions that immediately comes up is why? Why does gun violence act the way that it does? Then-Yale associate professor of sociology, Dr. Andrew Papachristos had that same question in the mid-2000s and answered it through a research study, titled Modeling Contagion Through Social Networks to Explain and Predict Gunshot Violence in Chicago, 2006 to 2014.

Using the underlying principle of Papachristos’ research, the spike in gun violence around the late nineties can be attributed to something called the contagion effect. When it pertains to gun violence, ‘contagion’ is the idea that the change in gun violence trends can be compared to that of a virus. This explains the wave-like nature of gun violence over time. It also serves to explain outbreaks in armed violence, like the short stretch from 1996 to 1997.

In the study which was published on Jan. 3, 2017, in JAMA Internal Medicine, Papachristos’ research team studied the probability of an individual becoming the victim of gun violence using an epidemiological approach.

“Academics, when they study these things, contagion, or spread, a crime rate, what has an impact? So I started trying to think about how it actually spreads. One of the questions I had was, ‘Do you catch a bullet like you catch a cold?” Papachristos says.

The study analyzed a social network of individuals that were arrested over eight years in Chicago through an epidemiological lens. Of the 138,163 participants arrested between Jan. 1, 2006, and March 31, 2018, 9,773 were subjects of gun violence. One of the other questions Papachristos and his team were trying to answer was whether or not there was an element of randomness to gun violence. The answer to that was, no.

“When we look at disputes or the distribution of violence, whether it’s Chicago or Oakland or New York or New Jersey, or Evanston, violence concentrates in a small number of places, specifically in the social networks. This is true through lots of social phenomena. But one of the things that say is what type of epidemic is it? It’s not as contagious as COVID or the flu, it’s very specific. It’s more like Hepatitis C or a sexually transmitted disease,” Papachristos says. “You have to do certain things or be in certain situations to contract it,” Papachristos says.

The results of the study concluded that social contagion accounted for a staggering 63.1 percent of 11,123 gun violence episodes. Subjects of gun violence were shot on average 125 days after their “infector,” a previous victim of gun violence that the subject knew. The way this was mapped out was very similar to tracking an infectious disease.

“Back in the early 2000s, one of the things we did was we took shooting cases, like you see in the old movies. I started making connections between individuals in cases literally trying to map it out,” says Papachristos. This is almost the exact same thing that contact tracers do when tracking COVID-19 cases.

“It’s this network science,” explains Papachristos, “Especially in epidemiology where they use it to track diseases. I took those methods and started applying it to records of shootings, arrest records, and other sorts of records to see if I could create or trace this information. It’s contact tracing.”

One of the common themes in the outbreak in the nineties was gangs. Whether it be Walker being shot because someone thought he was a member of a rival gang or Lazcalo reportedly throwing up a gang sign after he had shot Young. However, as Papchristos explains, stereotyping all gangs as dangerous can only worsen the problem. If people think that gangs are unsafe, then people will feel unsafe, and one of the reasons people carry guns is to feel safer. It’s a vicious cycle.

“Most gangs are not highly organized. Groups are not like you see in the movie Training Day; they tend to be smaller crews of guys from a particular neighborhood who get together for protection and for fun. Sometimes, they get involved in illegal behavior. Most of the time they don’t,” says Papachristos, “But conflict is a really important element. So if you’re afraid of one group, your gang might say to start carrying a gun because they feel the need for protection. Gangs don’t create gun violence, but they can amplify it. They can also amplify everything because there’s a built-in group process.”

The group process refers to the connection between the members of the gang. If someone calls another person a name alone, they can easily walk away. They don’t know each other, or care. But when a group dynamic is built-in, everything changes. Another member can say something like, “Are you just going to let him say that?” and the situation escalates. If another member says that and they have a gun, then everything changes again, especially if there are people pressuring others to use it. That’s when the dynamic becomes very dangerous.

The conclusion of the study, through intensive research into gangs, social networks, and armed violence, was that gun violence follows an epidemic style of contagion, that it is transmitted through people by social interaction. One of the outbreaks was in Evanston in the late nineties, and one could argue the city is going through one again now.

***

The first case in this recent wave of gun violence in Evanston, the index case of the new wave, occurred on Nov. 28, 2021, the Evanston Police Department responded to multiple 911 calls at a Mobil gas station located just off Green Bay Road. They arrived on the scene to find five wounded high school students. One of them, Carl Dennison, senior at Niles North, died on the scene. While the remaining four survived, so did the trauma from their experience.

Then, a month later, ETHS was put on lockdown on December 16, 2021. The “code red” was called after students were found to be smoking marijuana in a bathroom in the school. When Safety searched them, they discovered two handguns and immediately recovered them. As the school and the police determined that the building was secure, a lockdown was called. While there was no active shooter, the memory of that day lives vividly in the mind of students.

Six months later, on Aug. 28, five-year-old Devin McGregor, a kindergartener at Willard Elementary School, was shot. He was so full of life that his family members gave him the nickname “Boom” for his upbeat attitude. McGregor was so excited to have started school that he wanted to go and visit his father in Rogers Park to tell him all about it. He was just getting buckled in for the car ride home when a black sedan pulled up and fired shots at the family. McGregor was shot in the head. He passed away a couple of days later.

On Sept. 2, there was a shooting at McDonald’s, only a few blocks from ETHS. Although the shooting was targeted, an isolated incident involving only two people that likely had a previous conflict, the event still scared many in the area. It made students unsure whether or not the school would be safe.

One of these students present at the shooting was sophomore Ethan Arnold. It was an ordinary afternoon as he walked to the nearby Starbucks with some friends. He suddenly heard three gunshots and started to get concerned.

“There was this big delivery truck right by the Starbucks. I heard a clattering noise, because I guess it broke the glass of the car the guy was in. And I thought it was the truck. But a couple of my friends who were by the McDonald’s ran by, and they’re like, ‘There’s a shooter!’ I was like, ‘No, there’s not. What are you talking about?’ I wasn’t entirely convinced there was a shooter, so I was nervous but not freaking out,” says Arnold.

“When acts of mass violence are repeated in this way, they start to feel more and more [overwhelmed], and a sense of hopelessness starts to set in. Human bodies are not meant to be so frequently in a state of agitation. Some people may become desensitized to violence as a defense. People feel so overwhelmed by the stress and worry that they have to compartmentalize it to a certain extent,” said Vaile Wright, senior director for healthcare innovation at the American Psychological Association (APA) in an interview with The Washington Post.

Arnold is one of many who have experienced this phenomenon of desensitization.

“The lockdown was scary for me, although I was kind of tucked in a room that was far from any entrances. When I had to go inside the Starbucks and hide, I wasn’t as freaked out this time, just because I had been through the process before,” Arnold says.

The many close calls with gun violence have affected Arnold in irreversible ways.

“I’m definitely very cautious. If I hear a loud noise, I’m like, ‘Whoa, was that another gun,’ and I always have an escape route. So even at school, I have a little plan for how to get out of whichever room I’m in,” Arnold says.

On Sept. 12, the ETHS School Board held its first meeting of the school year, focusing on gun violence. There have been numerous instances of high-profile gun violence in Evanston and the surrounding areas in recent years, such as the killing of Devin McGregor and the shooting at a McDonald’s on Dempster, only a few blocks away from the school. These instances have hit close to home, especially for an Evanston community with little experience in these situations. The ETHS School Board met to discuss, among other things, gun violence and its growing presence in the Evanston community. The school views gun violence as a public health issue. However, it was not made one of the key priorities the school announced heading into the school year—literacy, equity, post-high school planning and social-emotional learning.

Multiple board members voiced their support of action to prevent violence in Evanston.

“At ETHS, we don’t shy away from difficult topics. [Gun violence] has got to be pretty up there in one of the most difficult topics. If a topic makes us uncomfortable, we still go there, because we recognize that it’s important for our students to dive into these topics,” president Pat Savage-Williams says. “There’s been a lot happening. Our students have been threatened, traumatized and hurt; some have even been killed. That’s been happening. Educators and parents have lived with the reality that gun violence and shootings seem to be a part of our community. It’s not just Evanston; it’s nationwide, like an epidemic. It’s put us all on edge. Our kids are scared, our staff is scared, I’m scared.”

On Nov. 9, an incident occurred at ETHS where a student was found to have had a gun inside the building. The retrieved gun had not been fired. Administration, in conjunction with the EPD, had determined that there was no active threat of violence to any students or staff, which is why a lockdown was not called.

“My first day on this job was July 5. The first thing I have to do is get a message out about the violence to our friends in Highland Park,” says Superintendent Dr. Marcus Campbell. “I began to think about last year’s events, the lockdown. Think about what happened over the summer, where a 10-year old came to camp here with a gun. And I’ve said this over and over that the proliferation of guns in this country and in this community puts us all at risk. So when the murder happened last year, at the gas station, that set a lot of motion, and a lot of students tell me that they’re scared.”

Tervalon Sargent, McGregor’s grandfather, explained how guns had impacted him and others in an interview with ABC 7 Eyewitness News.

“You see it all the time, but it never hits until it happens to your family, and now I’m a part of another family because I’m a part of the families that this has happened to, and it’s the worst feeling ever. All these kids want to do is go to school and play, and they can’t even do that. That’s messed up. They can’t even do that, and it just keeps happening. It just keeps happening. We got to do something. We got to do something.

“We got to do something.”

***

The ETHS administration has been struggling to find a solution to guns in the school.

“I’m trying to figure out how to partner with the city. What can we all do together to help our kids feel safe? What needs to happen? What is happening on the city side?” Campbell says. “And so the city’s addressing their concerns. They are working with families that have been impacted by the violence in the community. For example, if a student has been impacted by violence in this town, we’ve got to provide them an education. How is the city supporting [that effort]? Our social workers and other mental health professionals are doing a little bit of talk therapy for students, but they don’t prescribe meds. They don’t diagnose. We’re working with the city to get a more collaborative effort going, so that we are all talking about what [the administration] sees from an education side, or what they see from some of the residents rather than just so we have a lot of differing plans in motion. I feel really confident in what I’ve heard from city officials so far.”

Guns have been a problem for much of Evanston, but it’s challenging to devise a solution to gun violence because it’s such a complex issue.

“We don’t actually know why [gun violence] went up after 2020,” Papachristos says. “We don’t know the reasons why it was down earlier, and there’s not one thing that happened now. There was a confluence of things that happened that made gun violence and homicides escalate the last couple years.”

That fact—that there are a number of factors that have amalgamated into the problem of community gun violence— makes it extremely difficult. Every answer has it’s questions, for example, does the benefit of student resource officers and metal detectors outweigh the possible racial profiling that has become so synonymous with those solutions?

“Experiencing gun violence is trauma, and living with the fear of gun violence is also trauma. Many of our students live with this trauma, impacting every aspect of their lives. Trauma is both the outcome of and the precursor to violence, creating a vicious cycle. Evanston has recently experienced increased gun threats and violence, which has caused great harm to our community,” third-year board member Elizabeth Rolewicz said.

“In addition to those who are victims of gun violence, there are many people impacted by the violence as it ripples through communities. There are many factors that contribute to a culture of gun violence, and this makes it a very difficult problem to solve,” she said.

Solutions have been proven effective on a national scale in other countries by implementing harsh gun laws. Still, it is challenging to control gun violence locally when gun laws are regulated at the federal level of government.

“I think that there should be further psychological testing and to have shown a need for a gun before someone can purchase one,” Arnold says.

Solutions presented in other countries have worked, some similar to those that Arnold proposed. Evanston and the U.S. can look towards these countries for inspiration. In France, the right to own a gun is not inherent in its constitution. To own a gun, you need a hunting or sporting license that requires a psychological evaluation and must be renewed yearly. The punishment for having a firearm without a valid license is a fine and a maximum of seven years in prison.

This comparatively stringent law works well in France. According to statistics, the French suffer 0.2 deaths from firearms for every 100,000 people. The United Kingdom has also instituted strict gun laws, effectively preventing gun-related violence. The numbers in the U.K. are 0.17 deaths per 100,000. In the U.S., that number is more than ten times worse at 2.8 deaths from firearms per 100,000 people. This proves the idea that not only fewer guns will mean fewer deaths from guns, but a higher degree of difficulty to gain access will also mean fewer deaths as well. This is fine on a national level, but at the local level, not much can be done in that capacity.

The end goal though is to make students feel safe. That is the most important thing. ETHS’ administration has noticed an uptick in violence near the school, and with the idea of making students feel more secure, the administration instituted new policies on safety after an assessment was conducted by an outside company, Facility Engineering Associates (FEA). Some of these changes are extra staff training, enhanced monitoring of entrances and exits of students and staff and signage explaining ETHS’ policies against weapons of any kind (such as guns, knives, and pepper spray).

“We have an immediate thing that we need to address…what’s the long term plan for the accessibility of weapons in town. How do we make me feel safer?” Campbell says.

These policies were all implemented with the safety of students in mind

“I’m on the City Benefits Reimagining Public Safety Committee,” says Papachristos. “People don’t feel safe, so they’re going to do stuff to protect themselves, and one of the things they do is they’re going to carry weapons. So everything should be done with that kind of sense in mind. But the most important thing I would say is you want students to feel safe. The key is you need people to feel safe. There’s not one particular thing that can be done, whether it’s just more security, or whatever; it won’t work on its own. I don’t know what I would do if I was running a school with [4,000 students,] that’s not even a question I’m going to try and answer.”

***

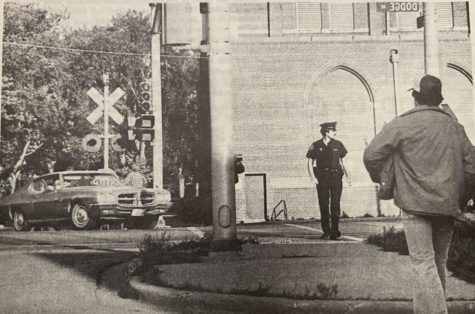

After the death of Hoffman in 1997, students at ETHS took action. On Monday, June 9, the call of the wards occurred. The call of the wards is a forum in which council members may raise various issues affecting the community. It is an opportunity for the Evanston community to come together and speak out about difficult topics. There was one major topic on everyone’s minds that night, the murder of Hoffman just four days before.

Hoffman’s killing was a series in a larger portion of events, featuring the killing of Andrew Young, as well as Ronald Walker II, both former or current ETHS students. The butchering of Hoffman provided a spark for students around the school. They organized a rally against violence, which took place on the anniversary of the slaying of Young. Around 100 people gathered along Dodge Avenue to make their opinions known and memorialize the late Hoffman.

To make sure their voices were heard and that no change would be left to chance, the students leading the rally presented a “Petition Against Violence” at the call of the wards. The petition was signed by more than 75 people, and praised by Fourth Ward Alderman Steve Bernstein.

The petition read, “We, the students of Evanston Township High School, demand action from those with the power to make changes. We demand the creation of a plan which will stop the senseless violence which has engulfed our community.”

“They issued us a challenge,” said Bernstein at the meeting, “We’ve been grappling with this problem for (20 years) and nobody has come up with a solution. What I think we must do—and we must not wait a minute longer – is to declare a war on violence in this city. I don’t have any of the answers, but I think it’s incumbent on us as a City Council to come up with these answers.”

25 years later, Evanston is dealing with the same problems.