Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Nashville in November 2025, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

Food deserts: A reflection of a failed system

January 27, 2023

A refrigerator lies just off the sidewalk on Dodge Avenue, two blocks south of ETHS. It carries everything from carrots to donuts; mac n’ cheese to lemonade. It’s one of four fridges in Evanston, run by and for the community.

From that fridge, walk three blocks north, past ETHS, to the C&W Market. The store, rooted in community trust, gives out hundreds of free meals to families and elderly folks every month.

Then, from C&W, it’s a 10-minute walk to the Fleetwood Jourdain Community Center. The center is home to a community garden run by Evanston Grows, a post-COVID-19 startup that serves community members who cannot easily access or afford healthy produce.

In the context of nationwide food inaccessibility that disproportionately affects Black and brown communities, massive Chicago food deserts less than 30 miles from ETHS and big grocery stores’ refusal to offer their services to low-income communities because it’s not profitable enough, these community-based efforts have been crucial for countless Evanston residents.

“There’s enough food in America to be able to make sure people have something to eat. We’re just doing our part to contribute to make sure the families that we can get to, or they can get to us, have something more than what they had the day before,” says Clarence Weaver, who owns C&W alongside his wife.

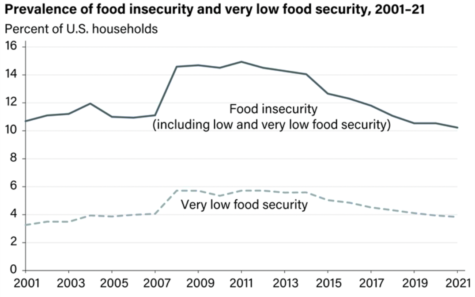

Food insecurity has been a pervasive problem in the United States since the Great Depression, when a quarter of the American workforce was unemployed and food couldn’t be sold for profit. Since then, the U.S. government has made many attempts to combat food insecurity.

One is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Formerly known as food stamps, SNAP helps low-income households get the food that they need. The government also manages several child nutrition programs and food distribution programs. While decades of government assistance are helpful for millions of Americans, they have proven to be no more than adequate solutions to the hunger crisis.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 10.2 percent of Americans were food insecure in 2021. That number is echoed in the millions of parents who struggle to afford to feed their children, especially with fresh and nutritious fruits and vegetables.

There are two main reasons why people can’t access fresh food. The first is location. Millions of people don’t have access to nearby grocery stores with fresh produce. For example, around 30 miles from ETHS, entire neighborhoods like Riverdale on Chicago’s Far Southeast Side have no grocery stores within a 0.5-mile radius. For elderly people and people without a car, it’s very difficult to make such a long trip for fresh food. The second is affordability. Especially with recent inflation, buying fresh produce simply isn’t an option for those who can’t afford it.

“Even if there’s healthy food in walking distance, it may not be affordable. And so there’s not enough being done in the industry and at a local level to make sure that healthy food is affordable to everyone,” says Anna Grant-Bolton, the Outreach Organizer for Evanston Community Fridges. “So why is that fresh food so important? When you were younger, you probably heard adults telling you to, ‘Eat your vegetables!’ They didn’t just say that to make you hate broccoli. They said it because healthy food sustains us.”

Debbie O’Connor, a board member at Evanston Grows and an advocate for the nutritional education of youth emphasizes why eating healthy food matters.

“It’s really hard to [get through your day] when you’re eating all this processed food. But when you’re fueling your body with whole foods, it really does affect your ability to think straight, to do your homework, to go out and run and exercise and things like that,” she says.

Despite the importance of healthy food, big grocery store chains don’t see it as profitable to set up in low-income communities. A few months ago, a Whole Foods in Englewood, a major food desert, shut down after six years in the community. Many were disappointed by the decision, especially given the company brings in billions of dollars in revenue every year. Among them is Chicago 16th Ward Alderwoman Stephanie Coleman.

“The fact that [Whole Foods] did this after six years when we celebrated their five-year anniversary as a part of Englewood excellence put a dagger in our hearts,” she told Block Club Chicago. ”We’re not a failure. They failed us.”

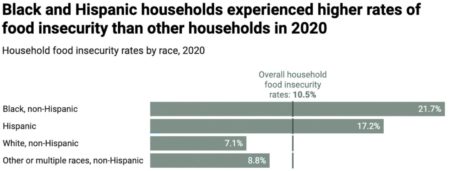

Food deserts are also rooted in systemic racism. For example, Riverdale is 95 percent African American, and that’s no coincidence. According to the Center for American Progress (CAP), “Over the past 20 years, both Black and Hispanic households have consistently been at least twice as likely as white households to experience food insecurity… In 2020, 21.7 percent of Black households experienced food insecurity, as did 17.2 percent of Hispanic households and 7.1 percent of white households.”

These numbers, CAP says, are the ramifications of centuries of decisions by politicians to “exclude Black and Hispanic families from the systems and institutions that allow many white families to build financial security, collect generational wealth and experience economic mobility.”

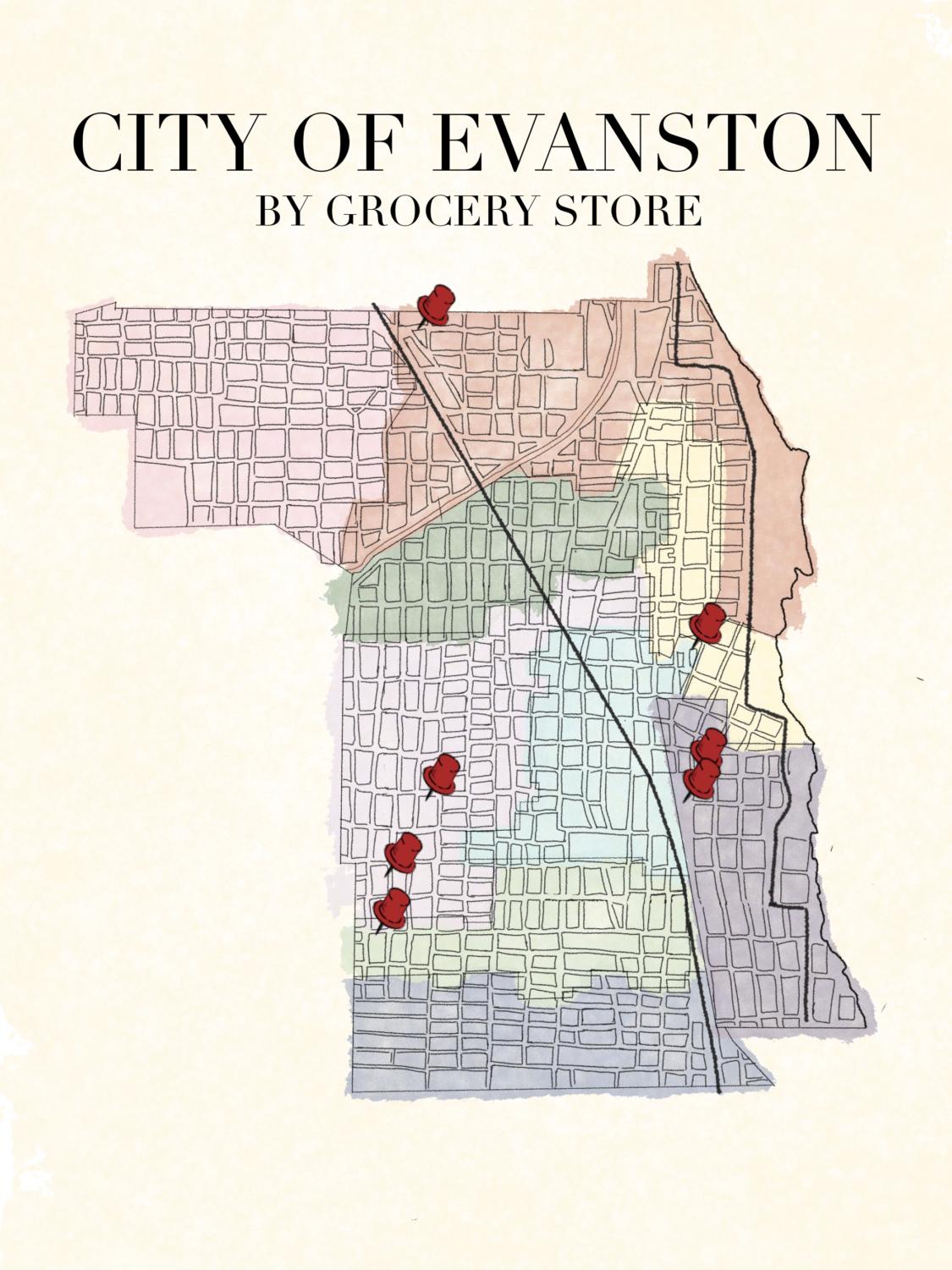

In Evanston, there are five big-name grocery stores across the city, but that doesn’t guarantee that all residents have easy access to them.

“If you’re anywhere in between [the Evanston grocery stores], it’s really not easy for you to get there, especially if you do not have transportation and you’re taking public transportation,” O’Connor says.

The situation isn’t all negative, though. While big grocery stores have failed low-income communities and government assistance programs haven’t been enough, community-based solutions have emerged as a huge part of the battle against food insecurity. Three Evanston community solutions, in particular, have made big impacts on the community.

The first is Evanston Grows, which was founded in April 2021 to increase edible community gardens in Evanston. Evanston Grows has eight community gardens, five of which are situated in the Fifth Ward, which has an Evanston food desert.

“Having these community gardens within the City of Evanston is really important to not only create a community of camaraderie, but it also creates opportunities for people to see how everyone lives. Everybody’s coming from different places, but the thing that we all have in common is food. And having access to food is a basic right that everyone deserves,” O’Connor states.

Evanston Grows engages the community by offering volunteer opportunities to high schoolers looking to spend an afternoon laying down soil or planting tomatoes. The organization emphasizes that Evanston Grows doesn’t run unless the community pushes it forward.

That’s the same message that the Evanston Community Fridges lives by. The fridges were created in conjunction with Evanston Fight for Black Lives to combat food insecurity in the Black, brown and low-income communities of Evanston. The four public fridges in Evanston are filled by community members with the idea of providing for those in need. However, the group believes that anyone who wants food can take it, no matter their demographics.

“Our motto is take what you need, leave what you can. So the purpose of the fridges is to ensure that every community member in Evanston, every neighbor of ours, has food to eat if they want it,” says Grant-Bolton.

These community efforts aren’t limited to nonprofits and startups. C&W Market and Ice Cream Parlor has been in business right across from ETHS since 2014. When the pandemic hit and everything shut down, they stepped up in the community, handing out 200 meals a week to Evanston residents. Almost three years later, they are still packaging and delivering meals to families and elderly folks who need them. Unlike the big grocery stores, C&W doesn’t just want to make a profit: they want to build mutual trust with the community.

“[Customers] can come in and purchase if they’re capable. And if they’re out of work and then they find jobs, then they can become a customer as well. So it’s beneficial to be able to build a relationship, and then work with families from there,” Weaver voices.

All of these community efforts make a critical difference for countless families. But those efforts and ones like them across the country can’t fill the gap left by big grocery stores that don’t cater to the food-insecure people of America. The very existence of organizations like Evanston Grows and the Evanston Community Fridges is a reflection of a system that has failed to provide the most basic necessities for all people. They are a reflection of companies that value profit over people, and a country that carries the weight of centuries of racist policies.

Until the day that all people have equal access to affordable, healthy food, it’s up to individual communities to provide meaningful food resources for those who need them.

“I think people have to realize there’s always somebody out there that needs help,” Weaver concludes. “And whenever you can help somebody you should always do it.”