Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Nashville in November 2025, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

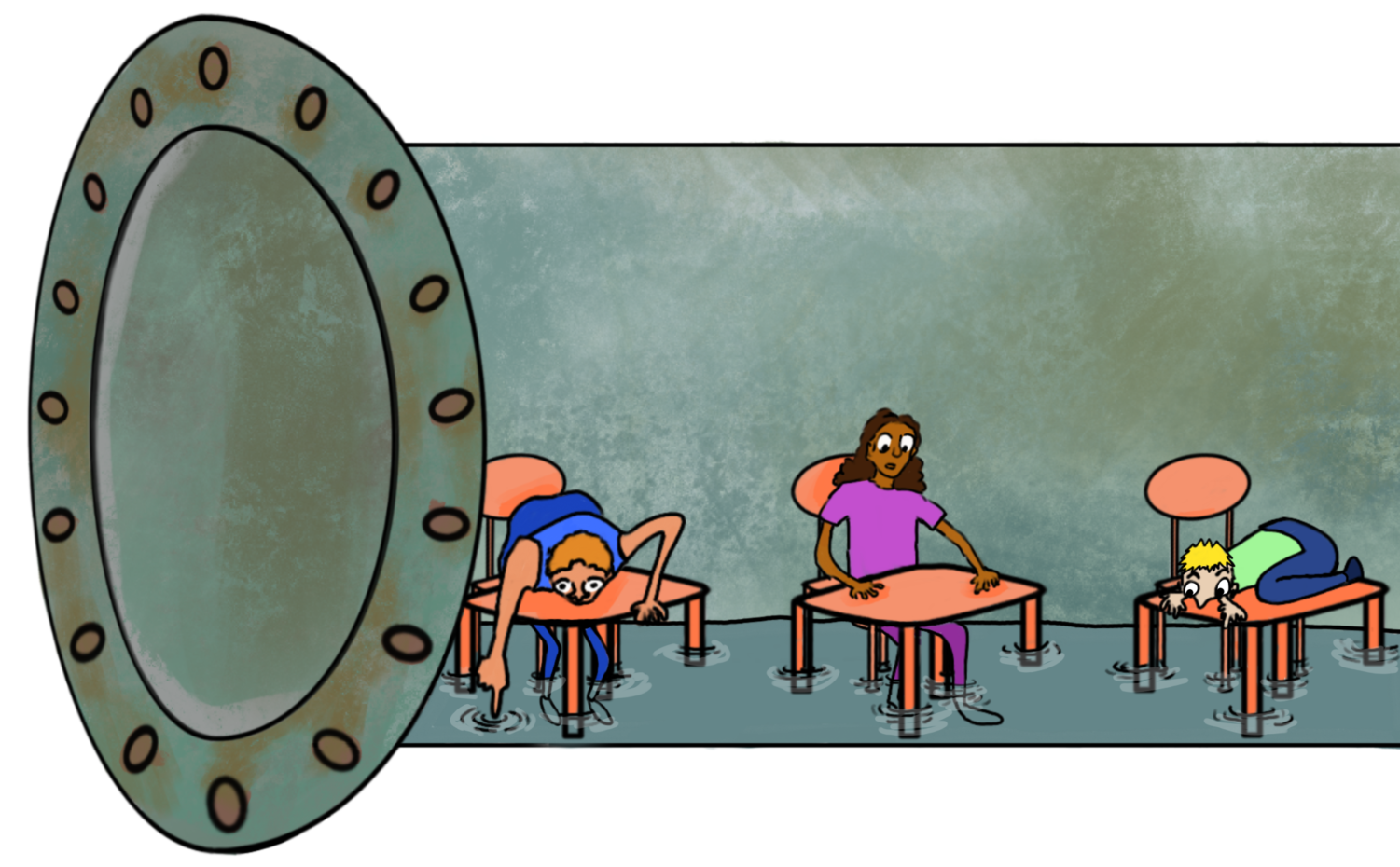

‘Get the Lead Out’

Evanston launches new efforts to remove dangerous lead piping from the community

April 20, 2023

When Janet Alexander Davis walks in the front door of her Fifth Ward home, she is grateful for the decades she has spent in Evanston. It’s the place where she grew up and where her kids and grandkids were raised. These days, as an active Evanston community member, her focus turns to the youngest generation, who she wants to see grow up in a safer and better version of Evanston than the one she grew up in. Part of a safer Evanston is safer drinking water, which means eliminating all lead pipes from beneath the streets of Evanston. The removal process of lead pipes is complicated, expensive and incredibly tedious, but it’s necessary for the city to successfully prioritize the health and safety of its residents.

Lead pipes have carried drinking water in the U.S. for centuries and across the world for millennia. Commonly identified as the cheapest and easiest way to transport water, lead pipes supply millions of American households and businesses. However, tracing back to the lead used in Ancient Rome, lead pipes have left a trail of poison and devastating health effects in their wake.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, even though those health effects harm adults, they are most damaging to children.

“Low levels of exposure in children are linked to damage to the brain and nervous system, learning disabilities, shorter stature, impaired hearing, and harm to blood cells. Exposed adults can suffer from cardiovascular disease and adverse impacts on reproduction and the kidneys, among other harmful health effects,” the report highlights.

The World Health Organization–a United Nations organization dedicated to promoting health–adds that children who survive severe lead poisoning could still suffer from behavioral disorders and intellectual disabilities for the rest of their lives. This reality magnifies the problem and fuels strong opposition to lead pipes from clean water advocates and concerned parents.

In the modern era, lead has consistently made headlines, perhaps most notably in Flint, Michigan. When city officials switched the water source of the roughly 100,000 residents of Flint to the toxic Flint River, residents complained of discolored and foul-tasting water. Disease ravaged the city, with 12 people killed by Legionnaires’ disease and countless others sickened by the water. Nearly 9,000 children were exposed to lead-contaminated water over 18 months, with the blood-lead levels in children doubling after the water source switch.

While the root of the crisis was the source of the water and not the lead pipes, these two problems are noticeably intertwined. Both issues represent neglect towards disadvantaged communities and a governmental failure to invest in those who need its help the most.

The failure extends to Evanston, where a large proportion of the lead pipes reside in the historically redlined Fifth Ward. The ward is made up of mostly Black and brown people with lower incomes, and has been neglected for generations by the Evanston government. In fact, before 2023, low-income Fifth Ward residents had to pay for their own lead pipe replacements, while the city only paid for the public side. Evanston Water Production Bureau Chief Darrell King explains what this means.

“Here in Evanston, the ownership from the watermain to the shutoff valve in the parkway, the city owns that,” King says. “From the valve in the parkway going into the dwelling, the property owner owns that, so there’s a separation of ownership here in Evanston.”

When the city’s policy was that Evanstonians had to pay for their side of the lead pipe replacements, it created a huge financial burden on low-income residents. Alexander Davis recalls that the cost of lead-free water would have been seven or $8,000.

Luckily, the new Evanston Lead Service Line Replacement Pilot Project enables the city to return to unreplaced pipelines on the private side and install copper pipes free of charge.

“[In] this pilot project, we’re going back to these 595 locations where the public side is already copper. But we’re going back and saying, ‘You know what, we’re going to get rid of these services on the private side, as well,’” King states.

The project is in tandem with Evanston’s Lead Service Line Replacement (LSLR) Program, which offers a free lead service line replacement from the street to the home’s water meter. This program is for service lines which haven’t had their public or private side replaced yet. Alexander Davis explains the importance of the city covering the cost.

“I’m very grateful because I didn’t have that money,” she says. “Senior citizens with reduced incomes, we couldn’t afford that, so we’re really grateful that’s going to happen.”

With the new programs, Alexander Davis will no longer have to worry about being exposed to dangerous chemicals. Evanston children won’t have to worry about getting sick after drinking a glass of water in their home. Evanston residents will have safe access to a fundamental right that many have been missing for far too long.

But how and when is it going to happen? Replacing lead pipes is a process, especially in Evanston, where 11,471 lead service lines flowed beneath the streets of Evanston in 2021. King says that number won’t dip below 10,000 until 2027, and it will take two decades to completely eradicate Evanston of lead pipes.

This information is a required part of Illinois’ Lead Service Line Replacement and Notification Act, which mandates municipalities to develop a plan to submit to the Illinois EPA. King says that all cities must have a plan to eliminate lead pipes finalized and implemented by 2027, but that Evanston got a head start in 2022.

With mandates in place and Evanston ahead of schedule, the key variable that is holding the city back is price.

“It could cost over $200 million to replace all these lead services,” King explains. “So if [the city] doesn’t receive significant dollars to cover this from the federal government and/or the state government, the ratepayers here in Evanston will have to pay for the replacements of these services.”

This means that, without a different way for the city to pay for lead pipe replacements, Evanston residents would be burdened with higher taxes to pay for the programs that are supposed to alleviate the financial burden on them. That’s why it is so important for the city to receive federal and state funding to cover the replacements.

In an effort to gain financial aid, Mayor Daniel Biss has been in contact with the federal government about potentially receiving funding for the costly replacements. He was at the White House in late January to join the Biden-Harris Administration’s “Get the Lead Out” partnership alongside other municipalities, states and organizations. Biss says it was a beneficial event for all parties.

“We’re pleased to [make lead pipe replacements] now with some federal money available,” he voices. “I will say there’s not enough so we need to find the resources to make sure we do this work because it’s really critical for the health and wellness of residents.”

While Evanston has many unanswered questions and years of hard work ahead, the city has emerged as a leader in the national effort to ensure clean water for everyone.

“A lot of places, they’re still making their community members–even if they give them a loan or something up front, they make them pay it back,” King emphasizes. “Evanston has decided to not do that and say, ‘hey, you know, we’re just gonna pay for it.’ And so I think that separates us.”

The city’s initiative doesn’t erase the reason why low-income residents were put in an unsafe situation. It doesn’t absolve the city of past wrongdoings and it isn’t a reason to forget about the struggles of the citizens of Flint and other affected communities. But it is a step forward in the process of healing historically oppressed communities and ensuring a safe future for Evanston youth.