Though Chemistry and Physics (Chem/Phys) classrooms are decorated with slate gray tables, intimidating lab equipment and chalkboards full of nearly indecipherable equations, the positive energy within them is palpable. Students sit in groups chattering excitedly about solving problems and conducting experiments, despite the fact that the Chem/Phys class is known to be one of the most difficult in the school. Beginning sophomore year, students alternate every day between chemistry with one teacher and physics with another. During that year, students are taught foundational concepts like stoichiometry, kinematics and Newton’s laws. If students choose to continue the class into their junior and senior years, they rotate between chemistry and physics every two weeks, covering more advanced topics such as coordination chemistry, organic chemistry and calculus-based mechanics.

Though the class is well-structured and clearly includes an enriching curriculum, senior Elizabeth Potosnak observed an issue that she often faced during her time as a Chem/Phys student.

“Chem/Phys is the class I’ve taken with the most obvious gender gap in this school. The course gives students a lot of freedom in when they do their work, where they do it, and with whom, as long as it gets done. This freedom is very telling of how gender separates the program. We get to choose where we sit, so the girls sit on one side and the men sit on the other side,” she said.

Potosnak isn’t the only one who has noticed a difference in the way students of different genders interact in the Chem/Phys environment. Terry Gatchell, one of the Chemistry teachers, explained a phenomenon that she noticed as a teacher.

“Male students will almost always be more outspoken in class, and they will sometimes dominate the discussion if I don’t intervene,” she said.

According to Potosnak, the issues that she has experienced in Chem/Phys regarding gender have been more indirect. However, she explained that these experiences still had an impact on her time in the class.

“Although the boys in Chem/Phys are not directly sexist, it’s often about what isn’t said. You ask a boy a question, and he answers it, but he rolls his eyes first. You go up to a group of boys to try to get help with a concept, and they all smirk at each other…Over and over, the guys always answer your questions, but they always make you feel bad for asking, so you stop,” she said.

Additionally, Potosnak emphasized that these gender-related problems aren’t related to the way that Chem/Phys teachers occupy the space. While she believes that it’s the teacher’s responsibility to make sure that students engage properly with the material taught in the course, it’s clear that that responsibility is fulfilled regardless of gender.

“I don’t think any of the Chem/Phys teachers, male or female, contribute to a sexist environment in class,” Potosnak said.

In fact, many Chem/Phys teachers, like Daniel DuBrow, make a conscious effort to include female students and amplify female voices in the classroom. DuBrow teaches sophomores on the Chem/Phys track, and understands that sometimes female students may feel less confident engaging with the material.

“One thing that I’ll do on purpose is if I ask the class a question during discussion and I see that there’s like 12 boys raising their hands, but no girls, I’ll just wait, and I’ll wait and I’ll wait. And eventually a girl realizes, ‘Oh, he’s waiting for me’ and I’ll call on them, so that I’m not always calling on boys, so that the voices of girls feel recognized,” DuBrow said.

DuBrow is just one of many Chem/Phys teachers who employ tactics like this one to create a space for non-male Chem/Phys students in the classroom. Emily Habbert, another one of the teachers for sophomores taking Chem/Phys, explained that she understands how much courage it can take to participate in discussion as a woman, so she tries to recognize it as often as she can.

“I feel like that validation piece can be big too, like making a comment after class like ‘You’ve never done a presentation before today, but it was awesome hearing your voice.’ So trying to find moments like that to offer some individual and personal encouragement, I think can go a long way,” Habbert said.

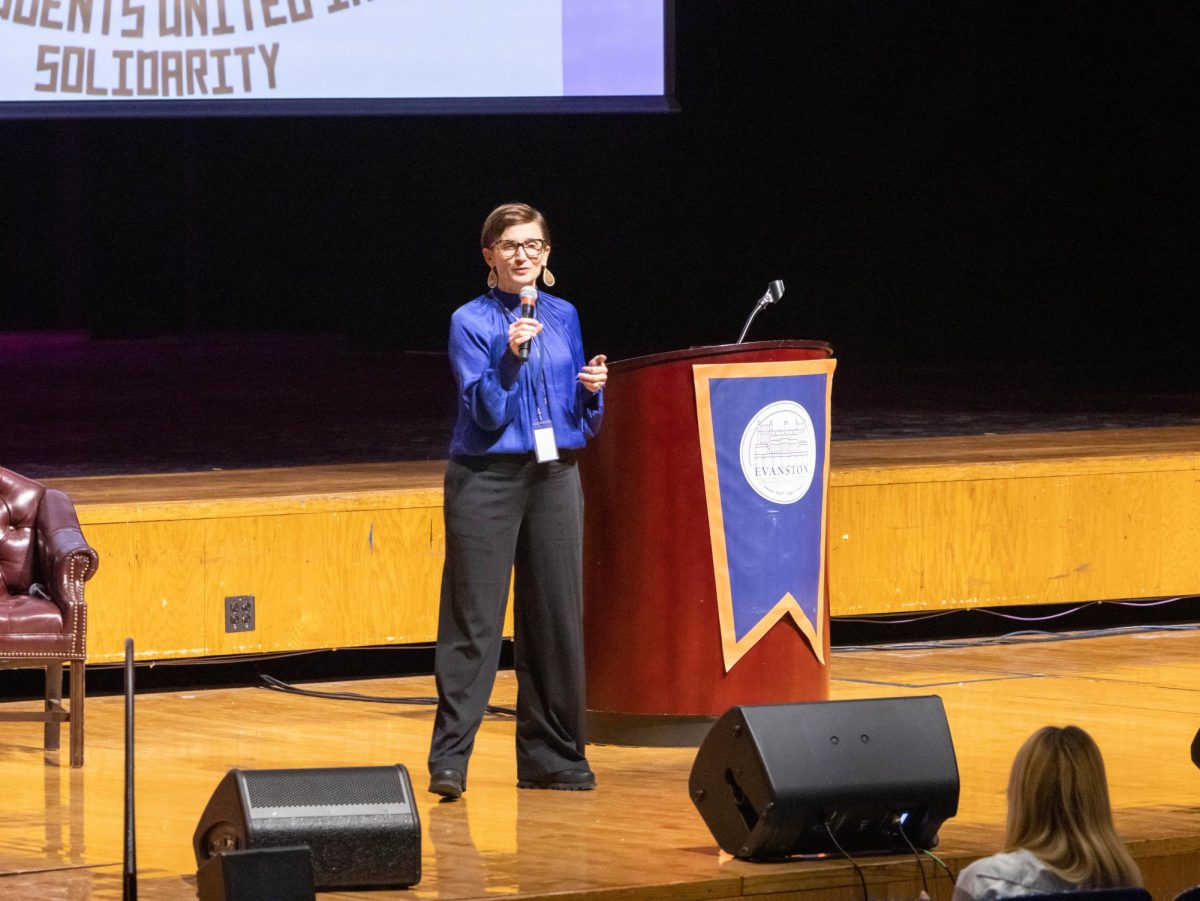

In addition to these methods, Mark Vondracek, a physics teacher for juniors and seniors in Chem/Phys, runs a mentoring program for female and genderqueer students in the class. The program connects sophomores taking Chem/Phys with upperclassmen, in an effort to create a space for non-male students to share their experiences and feel a sense of unity and support amongst their peers.

“I’m one of the senior leaders for the mentoring program and it’s amazing! I’ve been a part of it since I was a sophomore and it is such a welcoming and supportive community,” said senior Josephine Bonney.

According to Bonney, the group meets in the morning on the first Tuesday of every month in Vondracek’s classroom. During this meeting, students connect with their mentor groups, which are made up of all three Chem/Phys grade levels. Within these mentor groups, students focus on practicing studying techniques and building confidence to participate in the Chem/Phys space.

“We encourage all female and non-binary identifying Chem/Phys students to join our community. It’s a great opportunity to meet other students passionate about STEM and be supported by students who can give advice,” Bonney said.

Though, for students like Potosnak, gender inequality is still prevalent in the Chem/Phys space, these initiatives will hopefully allow female and non-binary students to share their voices without fear of judgment or ridicule. As Chem/Phys teachers and students alike continue to build confidence, connections and community, the environment of the class for non-male students will keep trending in a positive direction.