In-Depth: From middle school to high school

February 22, 2018

The Lock-Out of Low Income

Although the many historic attempts to integrate Evanston by means of busing were made with good intentions, the fight for integration within Evanston schools was not a complete success.

“My brother and I were both bused to Dewey, despite Lincoln being next to our house,” sophomore Megan Bezaitis says. “Busing broke up the sense of community, and it took a toll on the environment we grew up in.”

According to US Legal, desegregation busing is defined as the transportation of students to schools outside of their neighborhood, usually to achieve socioeconomic or racial diversity within segregated environments. Initially, it was the housing segregation in Evanston that that led to busing policy in order to integrate Evanston schools.

“In most cities, redlining was utilized in order to ensure that property values remained the same or increased. The gatekeepers of housing have almost always been upper-middle class whites who have used their own privilege and economic status at others’ expense,” ETHS English and History teacher Kamasi Hill says. “This has affected housing, schools and communities.”

The lasting effects of housing segregation in Evanston provided city leaders reason enough for busing in Evanston. However, over time, the execution of busing in public schools has become subject to critique and scrutiny.

“Integration should be certainly attempted; however, it should be done correctly, and, in order to desegregate a city, you must make some type of amends,” Hill says. “No reparations were given for the black and brown citizens of Evanston.”

In 1967, due to pressure from local groups seeking to balance Evanston, Foster School, a school located in Evanston’s primarily-black fifth ward, was closed down. This forced the students in the fifth ward to be bused to schools outside of their neighborhood.

“It was difficult to get to Haven because I lived further away than everyone else,” senior Jasmine Taylor says. “I felt detached from the school because I didn’t even live in the neighborhood.”

Additionally, students from the Evanston elementary school Walker are required to go to the Southernmost middle school, Chute, while there was often a closer middle school, Haven. Some students who live within the Walker-area travel almost three miles just to attend school.

“It was difficult for me because I had to wait forty minutes for the bus before school even started, and I had to travel far just to see my friends,” freshman George Van Nice says. “Even though Haven is closer to my house, I had to go to Chute anyway.”

While integration in Evanston had become official in 1967, to some, it seemed that no significant changes were made. Evanston was still as racially, socioeconomically and socially unbalanced as before.

“Integration is not about people living next to each other or coexistence. It’s about equal access,” Hill claims. “ETHS may have been ‘integrated’, but it could never truly come together without equity.”

In Evanston, one decision, the decision to integrate schools, affected each generation to follow. While many racial, socioeconomic, and social disparities still exist in Evanston, many would argue that these differences are not definitive of the town as a whole.

ETHS works to ease feeder school transition

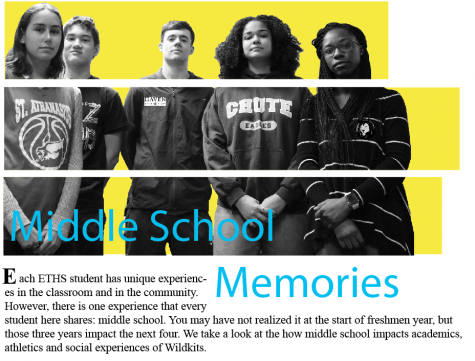

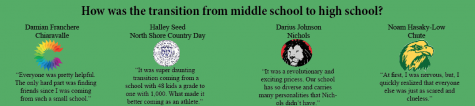

At the end of an awkward preteen phase, in the midst of adolescence and just a bit before adulthood, 14-year-olds are forced to face an epic transition: the switch from middle school to high school. This transition is particularly difficult for freshmen coming from non-feeder schools. For ETHS, this means students who do not primarily come from Haven, Nichols or Chute.

“Private school students perceive the size [of ETHS] as extra daunting because they are coming from a smaller class size environment, perhaps an ‘everyone knows each other’ environment,” New Student Transition Coordinator Alicia Hart says.

This does not come as a surprise. Evanston’s near 3,400 enrollment and 65 acre campus makes it the biggest high school under one roof in America.

“The building intimidated me a lot at the beginning, I was racing from one end of the enormous building to the next,” freshman Mikayla Hartmann says. Before coming to ETHS, Hartmann had been homeschooled.

However, size is not the only challenge that new students face; adjusting to the social scene also proves to be fairly difficult.

“The way that people interact with each other, the unspoken rules, I have had to get used to,” Hartmann adds. “But it wasn’t all that hard for me.”

“My transition was pretty smooth even though I barely knew anyone, because I was involved in YAMO and then shortly after I made many friends. Now it feels like I’ve known these people forever,” freshman Nikki Leeve says. Leeve attended Chicago Jewish Day School last year.

Hart believes the most effective way of combating the feeling of social isolation is simply making students feel welcome by inviting them to sit with them.

In hopes of easing the transition into high school for non-feeder school students, ETHS has implemented various initiatives to improve new students’ experiences.

For example, before entering their freshman year, prospective students are encouraged to attend an incoming freshman information night, a seminar that allows students to get comfortable and ask questions about high school. This night is typically held in November. Course selection follows that in January and finally, orientation takes place in August.

“During course selection night, we do a breakup by middle school. We try to connect perspectives from the schools so ambassadors can share honestly how it felt,” Hart says.

Additionally, there is a New Student Lunch that occurs once a semester. New students are encouraged to attend, even if they didn’t enter ETHS the semester that the lunch is taking place.

“We have lunches to start each semester and then we meet every two weeks after that,” Hart says. “We try to create a sense of community within the school for students who know what itś like to be new to the building.”

Transfer students from past years still come because they want to help lead and contribute to a welcoming environment. New comers are allowed to bring a friend that they made in school.

“Change isn’t easy for anyone, I mean we love routines as humans,” Hart adds. “I think that when other students affirm that everything is going to be okay, it helps ease that.”

Hart is open to ideas as to how to improve the high school transition process. Students can email her suggestions at [email protected].

Academic adjustment prompts change, builds maturity for freshmen

Freshmen’s academic performances are one of the most effective indicators of students’ high school success and college enrollment, according to a University of Chicago Consortium on School Research report released in the fall of 2017.

District 65 and middle schools at-large have emphasized preparation for freshmen year curriculum at their respective high schools; despite these efforts, some Evanston freshmen feel disparate levels of comfort with their secondary education.

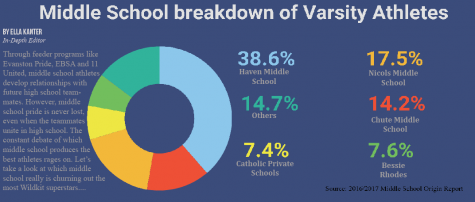

For eighth graders in ETHS’ larger feeder schools — Haven, Nichols and Chute — the focus on the transition into high school makes up the bulk of conversation in many social circles and classroom discussions. Despite the supposedly high awareness of the community and size of the high school, many ETHS freshmen feel academically underprepared for the jump to secondary school.

“Middle school barely prepared me for high school,” freshman Izzy Basso (Haven, Class of ‘17) says. “The teachers were very laid back and they made it seem like the workload was hard, but it’s way worse in high school.”

According to some students, these difficulties could simply be associated with the under preparation of certain students and the differing styles among teachers, or they could be attributed to a larger issue with differences of curricular expectations between Districts 65 and 202.

“[Middle school] was more about books we read and essays we did. It wasn’t about specific topics. It was more about past history, like the general reason why World War Two happened,” points out freshman Ellie Lind (Haven, ‘17).

There are, of course, exceptions to the trend of post-transition shock. For example, some kids from smaller schools feel that the intimacy and depth of their middle school instruction lends much of value to their careers as secondary students.

“My middle school prepared me well for ETHS because they taught me what to do when I encounter a problem and how to solve it in any subject or in general,” says freshman Nikki Leeve, who attended the Chicago Jewish Day School for middle school.

According to the District 65 website, the School Board approved the Racial and Educational Equity Statement in August of 2016, making explicit the district’s intentition to parallel ETHS’ equity mission. However, not all incoming freshmen can attest to experiencing the effects of D65’s equity initiative.

“[The middle school curriculum] was very white-centered history,” freshman Hazel Lietz says (Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Literary and Fine Arts School, Class of ‘17). “We talk about more prevalent issues [in high school]. Even though we were a magnet school, we never talked about racism.”

While current freshmen are still getting the swing of things at the high school level, upperclassmen have a simple piece of advice for getting over the hump: embrace the change.

“I feel that the rigor at the high school definitely caught me a little by surprise my first couple of months…but my teachers helped me with the change once I realized I needed it,” senior Adam Geibel states. “As I began my sophomore and junior years, school became a lot easier because of the help I got from my freshman year teachers.”