Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Nashville in November 2025, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

Tradeoffs and Triages: Students navigate mental health in e-learning

December 14, 2020

Trigger Warning: The following story contains information regarding mental health issues that may trigger some readers. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255.

The Mental Health Crisis

It’s no surprise that the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic seem to be never-ending. No aspect of life is untouched by this virus, and, as the majority of American students return to school through their computer, an unprecedented level of anxiety, stress and depression is hitting high school students, a population which had been dealing with surges in mental illness.

According to a report in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology, in the years prior to the pandemic, the rates at which teenagers reported symptoms consistent with those of severe depression increased by 52 percent, to a total of 9.7 percent overall. Rates of depression are most severe in teenage girls, with more than 20 percent reporting some level of major depression each year. Furthermore, rates of psychological distress—characterized by “feeling nervous, hopeless or that everything in life is an effort”—have increased by 71 percent in young adults between 2005 and 2017, and teen suicides increased by 56 percent in the same period.

“There is evidence that mental illness [among teenagers] is increasing, particularly things like depression and anxiety, as well as some other forms of mental illness,” Dr. Kathryn Fox, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Denver focusing on self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in adolescent and LGBTQ populations, says in an interview with The Evanstonian.

With these rising rates, it becomes increasingly important that resources are provided to those in need, yet, according to Mental Health America, “60 percent of youth with major depression did not receive any mental health treatment in 2017–2018. Even in states with the greatest access, over 38 percent are not receiving the mental health services they need.”

Even prior to the pandemic, these same increases in student mental illness rates seen at a national level were occurring at ETHS. According to the school’s most recent data, released in December 2019, there was a three percent increase in the number of students referred to Student Services staff from 2018 to 2019. No data regarding student referrals has been released for the second semester of the 2019-2020 school year or the first semester of the 2020-2021 school year.

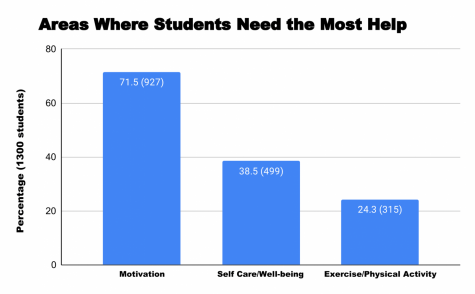

With these trends established heading into 2020, this year—which has seen a society-halting pandemic—has been particularly challenging. So, when ETHS presented results from the fall e-learning survey at the Nov. 9 School Board meeting, they were what one could expect: 72 percent (927) of student respondents indicated on a question asking which areas they are in the most need of support that they have been struggling with finding motivation while 39 percent (299) reported struggling with wellbeing since the start of the school year. These numbers exclude students who began the survey and did not answer a particular question. While there are limitations with this survey, notably a disproportionate amount of responses from white families and the fact that only 42 percent (1580 students) of the student body responded to any of the questions posed and a portion of the student response group only answered a smaller set of questions before becoming non-respondents for the rest of the survey, it does offer the widest perspective of the student experience currently available.

“There are a lot of hypotheses about the different ways that COVID, social isolation, stress in the home might be impacting mental health. There was some data that came out back in April that did start to show increasing rates of things like depression and anxiety, or at least higher levels of those kinds of symptoms,” Fox says.

Data released in an August CDC report support the hypotheses that Fox discusses, showing 74.9 percent of young adults reporting some adverse mental or behavioral health condition during the month of July. This translates to a threefold increase from the second quarter of 2019.

“A lot of people are feeling more mental health concerns. Many, for example, are dealing with depression. Understandably, students are feeling these issues because everybody’s normal life has been disrupted. People are trying to develop new habits, new interactions and new coping skills. It is difficult when people can’t get out; they can’t socialize; they can’t lead their normal lives—all of the things that human beings do,” Superintendent Eric Witherspoon says during an interview with The Evanstonian in late October.

Social interaction critical to the transition from adolescence to adulthood—and to the school environment as a whole—a lifeline that COVID-19 has robbed from students.

“A big part of being an adolescent, and really being a human, is being with people, spending time with friends, getting out of the house. Particularly during adolescence, a time when people are decentralizing the family as their primary social support…. A lot of people are hypothesizing that it’s probably really hard for teens to all of a sudden not have access to the support that they’ve been building up,” Fox says.

“I’ve kind of gotten used to the way that things have been, but that doesn’t really make it much easier,” senior Abby Persell says. “It’s been hard to have to do a lot of schoolwork without having a lot of the social aspects of school. When I go to school [in-person], we do school, but then there’s also all these parts where you get to see your friends or you get to eat lunch with your friends. I think the hardest thing for me is to not have that; it’s just school all the time, and when you’re not doing school, you’re just by yourself at home.”

Though the school administration has developed a multitude of services to make quarantine and e-learning less crippling, there are many roadblocks that prevent a majority of students from getting the help they need. Among these concerns are the stigmas that surround mental health, which serve as barriers to getting the support students need.

“It’s definitely intimidating to say, ‘Oh, I actually need to talk to someone about some thoughts I’m having’…. I was even scared to go into the office to ask for someone I could try to talk to. I was scared to even walk in there,” senior Emily Ho says. “I don’t know how people feel about that being online now—I didn’t have to go through the entire process of finding someone virtually. But trying to admit the fact that I should probably talk to someone about my emotions and mental health, it’s just really, really frightening.”

“I think the administration is trying, but the older generations don’t really understand [what we’re going through],” sophomore Gillian Aaronson, who spoke with the administration earlier this semester about her concerns about the way in which the wellness curriculum handles eating disorders, says. “I think a lot of people are embarrassed to get help and scared to talk to people.”

The stigma around the very existence of mental health has severely hindered the ability of people in need to seek out the help they deserve. These harmful beliefs have decreased in recent years, but there are still multitudes of people suffering silently. Children and young adults tend to receive less mental health care, often being overlooked or having their feelings passed off as normal teenage angst. No individual institution—schools, governments, media—can break this stigma overnight; that work takes years. However, these stigmas do prevent students from getting the support they need and stifle work being done by administrators, teachers and social workers.

“It’s really about creating an atmosphere where there’s less stigma about mental health and around reaching out for help. One of the biggest issues that the school, and their mental health system, really needs to talk about is that students don’t need to hit rock bottom to get help. You should be able to ask for help before you’re in a crisis, or before you’re in an emergency, and that’s something that needs to be more normalized,” senior Gloria Jen says.

“Most people who struggle aren’t getting mental health care for a variety of reasons. Financial costs and insurance coverage are one of the barriers, but there are also triggers in how we talk about mental health issues and what it means to get therapy,” Fox explains. “It’s so hard. People do mean really well, and it’s really hard to make a difference on a large scale.”

In the case of ETHS, the data is clear: there is a systemic crisis facing students. Beyond the 39 percent of the student body reporting needing support with their wellbeing, according to a survey conducted by Student Union, over 65 percent of student respondents (389) feel “highly stressed.” That survey garnered responses from 16 percent of students (598) and, like the ETHS fall survey, disproportionately featured responses from white students. In 2019, ETHS reported that 12 percent of students received support from social workers, and based on all available data, the number of students in need of support has only increased.

At the same time, despite navigating an unprecedented situation, teachers and staff have worked tirelessly to meet the needs of students. Many teachers have implemented social-emotional learning techniques into their classrooms, and Student Services staff, including social workers, have been busier than ever. Still, students are struggling as e-learning continues into its fourth quarter.

As COVID-19 ravages the U.S. and the finish line for this virus remains out of sight, students are facing increasing course loads while dealing with isolation and a lack of motivation. These factors continue to harm student wellbeing and will continue to do so in spite of the resources provided by the school unless the very structures of e-learning detrimental to students are changed.

In the [Zoom] Classroom

From the beginning of the 2020-21 school year, the administration designed enhanced e-learning to ensure that students could return to as close to an in-school experience as possible while maintaining the physical safety of students and staff.

“What we’ve been trying to do is look at what are the components of the school experience that really matter and how can we do them in different ways, so we don’t have to sacrifice everything because we are remote. We have had national honor society induction, club meetings, Team ASAP Forum, conditioning, freshman orientation and so many other experiences using a virtual format,” Superintendent Eric Witherspoon says.

This process of analyzing the components essential to the success of a school environment was a major aspect of the work for developing a back-to-school plan over the summer. However, it, like all things, has come with advantages and disadvantages.

“We know that e-learning requires a lot of sacrifices and tradeoffs. There are so many things about being in-person and attending your school that we’ve all had to give up. I won’t pretend that e-learning is our first choice; I will say that it’s our best choice. We as a school—the faculty and everything they’ve put into this, what all of [the students] are doing in response to that now that classes have started—are really impressed with how everyone is making it work,” Witherspoon said during a separate interview in September.

“You can use [e-learning] to your own advantage. I don’t think there needs to be any loss of learning. You’re taking your math class, your physics class, your AP class, you have an opportunity to get all of that opportunity, to get all of that education that you would’ve had the opportunity for, but it’s more reciprocal; the students and the teachers need to say ‘Let’s make sure that every student gets out of this class the best that they can get out of it.’ While there are other kinds of sacrifices, let’s not sacrifice the learning.”

A survey conducted by The Evanstonian in September, which garnered responses from 13 percent of the student body (498), shows a 29 percent increase in the academic rigor reported by students in the fall semester compared to the fourth quarter of last year. However, the most glaring tradeoff that has come with the increase in academic rigor has been the stress that e-learning has caused students.

“There’s always been this belief after tragedies, when we were in the building of course, that students wanted normalcy, that business as usual was going to make them feel comfortable. That’s a little different now. We’re in an online setting, and they’re alone, so trying to normalize the kind of distress and trying to find opportunities to talk about the post-pandemic vision of the world is more important,” English teacher Erica Thompson says.

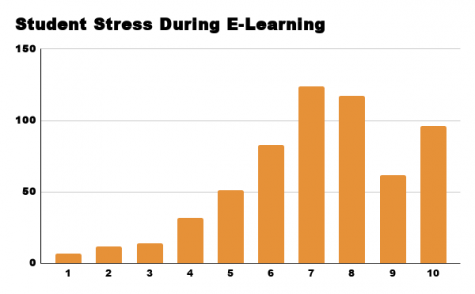

As previously mentioned, 65 percent of students have reported being highly stressed, according to Student Union, with an average student stress level of 7.2 out of 10. While there is no comparable data from years past, the large amount of student stress should not come as a surprise given the daily routine of many students.

The typical student school day consists of spending around 350 minutes (five 70-minute periods) in Zoom or Google Meets classes. 89 percent (1207) of students on the fall e-learning survey indicated that over half of each block is spent on live instruction such as lecturing or working in groups, while 28 percent (382) of students spend all 70 minutes on Zoom or Google Meets.

“[In-person] you get to connect with your classmates and your teachers, but with [e-learning], you’re mostly on your own. Especially through the calls all day, it’s pretty repetitive,” sophomore Sam Darer says. “Focusing during classes [has been a struggle], because there’s a lot of distractions around you, and there’s no one to keep you focused or motivated.”

In addition to synchronous instruction, Student Union data shows that two-thirds of students have between four and 10 hours of asynchronous work/homework each week, with an additional 15 percent reporting more than 10 hours per week. These numbers translate to an average of 6.8 hours of homework per week or 1.4 hours per day. This amounts to a total of seven-and-a-half hours spent on schoolwork every day.

The numbers provided in the Student Union data tell a different story than those presented in the ETHS fall survey, which indicates that students are spending an average of 3.4 hours on homework per week, or 40 minutes per day—less than half that reported by the Student Union. This number is closer to the 30 minutes of asynchronous work per week per class (three hours per week for a full-time student) that was announced at the start of enhanced e-learning.

While seven hours may be the length of the standard school day, there is a massive difference between completing this work at home compared to school.

“It’s difficult to engage with Zoom classes. Maybe you answer the warm-up question so you get your attendance, and then you don’t necessarily have to pay attention. You can always ask people for answers or something,” senior Emily Ho says.

Beyond the difficulties in staying engaged with classwork, the lack of structure in their learning environments has been a major challenge.

“Last year, I would have a specific wake-up time, and I try to go to bed by a certain time and finish all my homework by them. That was with normal school, extracurriculars and practice. Without all of those things, I actually have time that I have to figure out on my own; I’ve just struggled a lot with how I want to spend my time,” Ho says.

“I used to be able to study in the library or somewhere in the school and have that space; there’s this difference between doing work at school and then being able to relax at home. Now, you’re just home all the time, so you have to find a way to work and relax in the exact same place,” senior Gloria Jen says.

Compounding these concerns is the lack of student connections in the Zoom setting, connections that enabled students to more readily engage with school work.

“School feels like a long list of meaningless assignments that are all due by 11:59 p.m. That’s not what we need. We need intellectual thinking, conversation-based learning, rather than [repeating] two plus two equals four,” senior and Vice Student Representative Maya Moskal says. “We’re used to being up and on our feet, talking to people and communicating and socializing…. Now that it’s like all virtual, it’s just a never-ending cycle of boringness and depression.”

As part of the school’s efforts to combat the vicious cycle, staff have worked on integrating social-emotional learning (SEL) techniques into every classroom.

“[SEL] is teaching human beings as human beings—taking their lives, their needs, their personalities [into account]—and helping them develop the skills they need in the world. That’s how I see it,” history teacher Aaron Becker explains.

Becker, alongside fine arts teacher Karla Clark and math teacher Raquel Lopez, served on a summer task force committed to creating an SEL curriculum for ETHS teachers to implement in their classes; this task force was led by Associate Principal of Student Services Taya Kinzie and physics teacher Mark Vondracek.

“In middle school, and especially in high school, we’re programmed to be content teachers. We have to teach our subject, we have to prepare everyone to do well on the test, do this and that. We’ve lost, over a long period of time, addressing the full health of students,” Vondracek says. “When it comes to things like social health, emotional health, mental health, even, to some degree, intellectual health… We’re pretty bad at that overall, around the country and around the world.”

Not only are teachers tasked with overcoming the history of viewing students exclusively as learners, but they are also forced to learn how to teach remotely while losing an hour of instructional time every week. Furthermore, many teachers, required to teach specific, often rigorous curriculums under these new time constraints, are forced to move faster than ever.

“I told one of my teachers [that I couldn’t turn in an assignment on time], and she was really understanding of it. But, I told another teacher, and they were less understanding and supportive about it, so it’s been a mix,” freshman Miigis Curley says. “[One] teacher told me, ‘I’m sorry about that.’ I was asking to have an extension on a piece and let them know that I was turning in work late. It wasn’t the response that I needed, and it didn’t resolve my issue.”

Rigid, immovable deadlines run in the face of what SEL is all about, which is viewing students as humans and placing their wellbeing first.

“There’s a direct relationship between SEL and academic success; they go hand in hand,” Witherspoon says.

Students agree with the importance of implementing SEL techniques, even simple ones such as acknowledgment of student struggles and offering spaces for students to share their experiences.

“I feel there are a lot of motivation issues because of the pressures on us, and there’s not really anyone to give us any encouragement. Finding ways to continue to do your schoolwork, even though it kind of feels like all the days merge together, has been really difficult,” Ho says. “I feel like something to help motivate us throughout the school year… even just a small message or something would really help.”

“It’s just nice to know that your teachers care, and they’re thinking about what you’re going through. Just to hear, ‘I know that this is hard,’ before we get into content makes me feel a little better about if I’m not 100 percent able to engage and be totally focused on schoolwork,” Persell says.

While SEL has always been crucial in fully teaching students, the coronavirus pandemic enhanced the necessity of implementing it and ignited a passion within the administration to work with teachers and achieve a functioning SEL format in ETHS classes.

“I don’t necessarily think ETHS had ever had a formal SEL curriculum,” fine arts teacher and SEL task force member Karla Clark says. “It is because of the pandemic that administrators got together and said, ‘You know what, we need to move together on this to make sure that, socially, emotionally and academically, educators are paying attention to how we should care for our students.”

“When I presented [the SEL framework to] the science department, I think people were a little bit freaked out that there’s a pretty long list, there are so many different things you can do to get SEL into a science lesson,” Vondracek says.

SEL has existed in different forms at ETHS in the past—particularly in individual classrooms—but e-learning has shown that it is essential at a systemic level, not just the responsibility of individual teachers and staff.

“What the pandemic and remote learning have done is brought SEL teaching to the forefront of everyone’s minds and reinforced the importance of regularly and explicitly including SEL activities,” Becker adds.

As it’s not a mandated aspect of every teacher’s curriculum, SEL has yet to find its way to every classroom. Furthermore, not every teacher is even aware of the SEL toolkit and, perhaps more importantly, have not been trained in the implementation of SEL skills.

“It really depends on the teacher. Most of my teachers have a section on their website where they’ll talk about mental health. One thing I really liked is how some teachers have a Google Form check-in, where they’ll check in with you and see if you have anything you want to say; that’s a really direct way to be able to reach out. It really varies on the teachers though; some teachers don’t really mention [mental health], and other teachers are more proactive and will actually mention it during class time,” Jen says.

“[The school] provides us with lots of links to SEL supports and activities, including a site called Rebel Human that contains short meditations and relaxation techniques for students and staff. I’m not specifically aware of how other teachers are using these resources, because ETHS is a big place, and on top of that, we’re all remote right now, so I can’t really give you much insight into what others are doing in terms of SEL. I believe ETHS is definitely concerned about the mental—and physical—health and wellbeing of our students and their families. Quite frankly, it was a big issue even before COVID-19, but the coronavirus has raised the crisis to an entirely different level,” Thompson says.

“In general, ETHS gives teachers a lot of autonomy to figure out what our particular kids—every kid and class is different—need to feel okay and learn right now. There has been a lot of sickness, death and profound grief, and that needs to be at the forefront of our minds as educators—and as colleagues and community members. I encourage students to express their feelings and communicate, to process together, to advocate for themselves and others, to think more collectively and collaboratively, to envision and start to build a better, equitable world, one they want to live in and start to put that into practice The struggle for justice itself contains great restorative power for young people.”

At a time when flexibility and understanding are essential parts of what students seek, the lack of standardization of SEL in ETHS classrooms is a detriment to student wellbeing.

“Without any chances to do real training, this is brand new, published right before the school year started, it’s going to take us some time to get to some training in place and to really build this up with everybody, because most teachers have never done stuff like this,” Vondracek says. “Everyone’s under stress, including teachers. You don’t want to push too much on everyone while they’re trying to figure out online learning to keep everyone engaged. It’s a fine line. Should the administration demand that we start doing lessons like this, even without real training, or can we just build it over time? We don’t know when we’re going back to any kind of hybrid model, or any kind of live school, so that’s the hard part right now is how do you get people on board without shoving it down their throats, and how do you make it effective? Bottom line is, it needs to be effective; it needs to help get you in and handle the world that we live in right now.”

“The nature of classrooms in general needs to be more flexible. That way more students are accommodated…. [This includes] not having to be on Zoom consistently, for a whole 70-minute period, because I tend to work better when I’m not on the screen all day,” senior Journee Adams says.

Student Union released a set of suggestions and recommendations alongside its data which included a reduction of homework to no more than three hours a week from all classes, increased notice of upcoming assignments including asynchronous Monday work, more interactive lessons and breaks during lectures. In addition, “Students ask that teachers be mindful of everyday stresses compounded by the pandemic, racial and social unrest, and the election. Students also ask that teachers acknowledge and plan lessons with these stresses in mind.” The Evanstonian has presented its own recommendations in a letter from the editors.

Implementing some of these changes in the short-term and promoting and training staff to successfully implement the SEL curriculum in the long-term will make students’ lives easier during e-learning and, over time, open spaces that dismantle mental health stigmas at ETHS.

“There’s a lack of mental health discussions in Evanston. I think we’re very aware of current issues and what’s going on, but I think mental health is still one of those things that students and teachers don’t talk about,” Jen says.

Several teachers have made similar observations; not only that there are minimal mental health discussions, but also that ETHS has struggled with creating a space in which students feel safe to ask for help, which, at a time when additional supports are needed, serves as a looming barrier.

“There’s been a stigma around mental health in particular that you’re weak if you can’t handle it, if you have to go get professional help,” Vondracek notes. “That stigma exists in our community, so that’s something that we need to work on in a major way and convince people that you’re actually doing the right thing, you’re strong if you go in for help, that’s just the right thing to do.”

“It’s okay if you’re hurting, it’s okay if you need help; you have a lot of people out there who love you and want to help.”

Student Services faces obstacles

The ETHS Student Services department is a system of mental health professionals working to support students struggling with any aspect of their mental health. The structure of the department is to be a bridge for students to resources, such as counseling or emotional support. In a school of ETHS’ size, it can be difficult to work personally with every student in need of support. This becomes significantly more challenging during a pandemic.

“There are over 3000 students, but I think that, in general, we are able to assess a situation relatively quickly. [We can] figure out if we have the capacity to serve that person, and if we’re not able to because the schedule is full, [we] look for resources in the community,” Yolanda Kim, a social worker at the ETHS Health Center, says. “There are a ton of resources currently in the community, and that’s part of what social workers do is help connect you to the appropriate resources.”

ETHS’s framework for student services is standard for high school social work. A student is referred to the department and is contacted by a social worker. Then, prior to engaging parents and outside resources, the social workers or counselor works with the student identifying what assistance they may need.

The process of referrals is a complicated one, however. It typically begins with a teacher or other staff member identifying a student in need of aid. In non-remote settings, this can be accomplished by noticing changes in student behavior or through direct conversations with students. However, in a remote environment where, according to the fall survey, 79 percent of students (1064) keep their cameras off for half of the class period, these techniques become increasingly difficult given the lack of connection between teacher and student.

Once a teacher has identified a student in need of help, they are directed to fill out a social work referral form. This form asks for the rationale behind a report to Student Services and asks that teachers communicate with students before submitting a referral. Throughout the form, there are reminders that teachers should consult a series of teacher tools before submitting a referral and should use a separate zero contact form for students who have not engaged in e-learning. The zero contact form is intended for use if and only if a teacher has had, as the form states, “ZERO contact with the student and ZERO contact with the parent, the student has NEVER participated in a Zoom or online class, [teachers] have not been able to reach the student or their family [and teachers] have attempted to contact the student and family via all possible methods of communication [e-mail, phone, and Zoom] with no luck.”

Supposing that a teacher submits a referral, there is a delay of “up to two weeks for the referral to be processed” before a social worker reaches out to students.

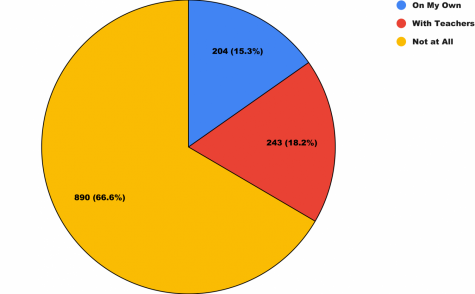

While teacher referrals are a primary way Student Services becomes aware of students in need, social workers and counselors try to promote drop-in meetings. During in-person learning, social workers allow students to drop by their office and talk to them. Since that more organic meeting is no longer available, scheduling times to meet with a social worker is more difficult. This especially is seen in student outreach.

“I would say I haven’t seen a big difference in the number of people asking for help, but it’s much more convenient when students are in the building, and they can go to the social work office or meet with their counselor or come here to the Health Center,” Kim says. “We can do a better job at letting people know that we are available during school hours, just as we always have been, and that we are flexible.”

The adapted process for student outreach involves emailing the student and asking if they would like to schedule a time to meet with a social worker or counselor. However, many of the referrals the department receives are due to non-engagement.

Despite the efforts of the Student Services department to provide students with mental health support during COVID-19, many students still feel the strain of school pressures and isolation. This is seen in the aforementioned fall survey data and Student Union survey data, which showed that 72 percent of student respondents on the fall e-learning survey are seeking support in terms of their motivation, 39 percent of student respondents on the fall e-learning survey are seeking support for their overall wellbeing and 65 percent of respondents on the Student Union survey are feeling highly stressed. There are many reasons why students are stressed and are in need of support in terms of wellbeing and motivation, but one main reason is the lack of personal connections with their teachers and their fellow students.

“We did train our teachers too at the beginning of the school year on the protocol. It’s different if your student is crying in the classroom because you can always call the social worker up or safety can walk the student down. But, what do we do if they’re home? What if they’re alone, and what if they’re suicidal?” pre/post hospital clinician and lead social worker Martha Zarate-Ortega said during an interview in October. “We had to really look at all those things and tighten it up a little bit and have a really good process to access those kids. We’ve tried different avenues of trying to reach out to students, but we’re also changing the protocols to provide those supports for students.”

“We’re offering almost everything, honestly. We’re trying to do our best with still providing individual counseling for students, so we’re doing that remotely, and we’re also doing groups. … Besides doing that, the social workers are also sending emails to all of the students and making sure that they engage by emailing [and] calling the parents. That gets a little sticky too because we also want to make sure that we provide confidentiality.”

In addition to this lack of direct connection with mental health resources, many students feel overwhelmed with school work during e-learning, which may result in a disregard for additional emails or information the school sends out.

“I think we sometimes probably flood with emails. We always talk with the administration about whether we want to send all these emails, because, sometimes as a parent, I get overwhelmed with getting emails from my kids’ school, so I want to put myself in their shoes too and say, ‘How much do we want to put in this email, and how often do we want to send it out?’” Zarate-Ortega said. “I think we’ve done a good job—we have automated calls, we have also the website where we listed so much information about COVID-19, how to support your students, and we actually also put the guide on there too for community resources. So, if a parent needs some other resources, they can access it through there.”

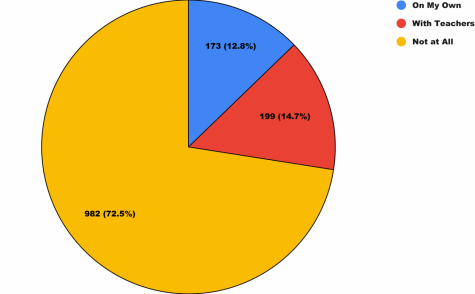

Despite compiling a number of different resources for students on the school’s Navigating the Emotional landscape of COVID-19 website, the results from the fall survey suggest that not many are accessing them, with 73 percent of respondents (982) reporting that they haven’t used the site, the main page for accessing mental health resources.

Even if that number trends upwards heading into the year’s second semester, no number of resources meant for individual engagement can remedy the need for connections that students are lacking.

“Most kids… love interacting with people and getting out of the house, which we can’t do now. I feel like one main part of why I miss school is the social interaction between me and my teachers. Yes, I miss my friends, but I miss my teachers and having those figures of authority… I still have them on a click of an email… but it’s just not the same as looking eye-to-eye and [hearing] that I have a bright future,” senior and Vice Student Representative Maya Moskal says.

Furthermore, what few social interactions do exist are becoming increasingly difficult to maintain as winter approaches and COVID-19 cases spike across the country.

“I don’t know what we’re gonna do in the dead of winter. I literally have been relying on daily walks with my mom to keep my mental health sane, because what else am I going to do? After school, I don’t want to be on my screen… I just want to go outside and walk…. What are we left to do? Sit in our house for the entire day?” Moskal expresses.

Kim talks about how she has observed seasonal changes and their effect on students’ mental wellbeing and outlook and how she believes winter will have a larger adverse effect on students than usual.

“We had the summer, and people were going out more, and then the weather has just started to change, so I suspect that it’s going to be more difficult,” Kim says.

Kim worries that the winter will lead to students feeling increasingly isolated. Remote learning will continue through the third quarter, so changes to the current services provided to students may need to be addressed to combat seasonal affective disorders.

“My anxiety and lack of motivation have been the two biggest struggles for me, so I’ve been using meditation and therapy to keep myself afloat,” junior Molly Ferguson says. “I go to therapy, which helps me, but if I didn’t, I would probably spiral. It’s been pretty bad as of late. My therapist gives me a lot of techniques to help me manage my anxiety.”

Because of the stress and emotional effects of this difficult time, many students need extra help and relief, but that relief cannot be provided to every student by the administration. The relief to isolation is not one that can be found in a breathing exercise or yoga class.

“I think the thing that all of us are experiencing is loneliness, the huge generalized way that we can’t be with each other. I don’t think there’s anything that any of [the staff] can do about that,” English teacher Elizabeth Hartley says. “If something bad happens, there’s usually a way to fix it. There’s no way to fix this.”

Admin responds to mental health

In addition to the work being done by Student Services and teaching staff in promoting mental health awareness and support, the administration has provided additional resources during these trying times.

“The mental health and social-emotional functioning [of students] is always a top concern, but now that we’re remote and increasingly isolated, it’s been top of mind,” Assistant Superintendent and Principal Marcus Campbell says.

Chief among these resources is Mindfulness Mondays, a set of online resources including a virtual calming room distributed by Campbell’s office weekly and available at any time that, according to the Mindfulness Monday’s website, encourage students “to explore, process, unplug or try something new” on their asynchronous learning days.

Aiding in this work is the Wilmette-based organization Rebel Human, which “provides training using fitness, breathwork, dance, meditation, somatic awareness and creative workshops.”

“We partner with Rebel Human to have more direct mindfulness support, with these videos, and yoga, meditation, juicing, all of that. It seems to be that the effort that the school is making [is being] taken well; [teachers] really appreciate the effort… and I think the kids do too,” Campbell says.

As Campbell mentions, Rebel Human, founded by ETHS alumna Jenny Arrington, provides a library of video tutorials to help students deal with stress and anxiety. These videos range from guided meditation and breathing exercises to dance lessons and discussions of healthy relationships.

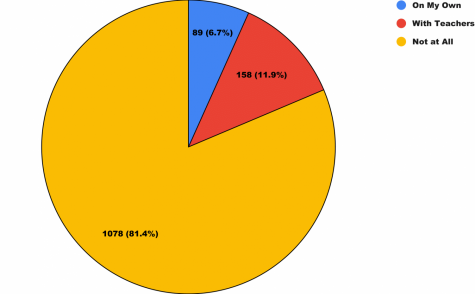

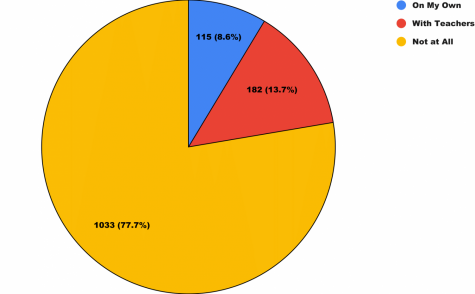

While this library is now available to ETHS students, data from the fall survey indicated that 81 percent of students (1078) have never used Rebel Human resources. The data tell similar stories about the ETHS Virtual Calming Room, with 78 percent (1033) saying they never used the site. The same survey also shows that only eight percent of students (105) take time on Mindfulness Mondays to engage in any form of mental health services including individual and group counseling sessions. The school chose more rigor, so when students are given a day to decide between taking care of themselves and keeping themselves afloat in classes, the vast majority of students, 92 percent (1238), reported spending their time completing homework assigned on Mondays with another 80 percent (1082) saying that they also take time to work on homework not assigned on Mondays. Student Union data reports an average of three hours spent completing school work on Mondays.

“It’s a lot harder to get information out right now. If teachers can bring it up, in their classroom or on the Google Classroom stream to provide that resource, social media and email updates are also good. The easiest way [to inform students about mental health resources] would probably be if teachers mentioned those resources directly in their classrooms so students know,” senior Gloria Jen says.

In addition to the challenge of effective communication during a pandemic, the onus of initiative remains on students. This is suggested by emails, such as this excerpt from a Dec. 2 email, that read “Students are encouraged to reach out early and often to get the best possible start” and “continue to seek balance and monitor [their] wellbeing.”

Whatever the reason for the lack of student engagement with these resources is, it is clear that only a minority of students are actively using them. As a result, there is little to no evidence to suggest that these resources have made an impact on student wellbeing; there was no question on the student wellbeing survey asking about the efficacy of such tools, data which should be considered when deciding what resources to continue distributing.

“As a whole, there needs to be more student feedback on the mental health services available and a normaliza[tion] of having more discussions around mental health. ETHS needs to create an atmosphere where students can have a voice and be heard around [mental health], because, right now, a lot of the conversations that are happening are by the adults leading the services, and not a lot of student feedback is being heard,” Jen says.

“Students are recognizing [what] they’re struggling with. That’s shifting a little bit, but, in large part, there’s been some consistency of concerns, and we’re responding to those as they kind of shift or grow. We continue to create groups and do individual services based on what trends are existing—whether that’s around anxiety, whether that’s around depression, whether that’s around loss…. We continue to develop nuanced pieces of each of those so that we’re not just typing out insights, but we’re talking about how we can build the skills we can use for the rest of our lives…. What we’re really continuing to do, now more than ever, in COVID is really triaging,” Associate Principal of Student Services Taya Kinzie says.

As Kinzie indicates, the role of the school administration has been one of triaging damage caused by the pandemic—determining which cases are severe enough to be tackled and allocating resources, staff and time in those directions. After all, there are only so many hours in a week for teachers and social workers to work to make connections and support students. However, because of the choices made by the school administration in advance of the first day of school, the school increased the amount of damage control it would need by creating a system that adds stress to students without giving them the outlets for relief in-person school typically provides

As previously explained, the enhanced e-learning model preserves the educational aspects of school while stripping away the human interactions and relationships that make for a successful school environment.

The need for human interaction in a school environment is one that has been acknowledged by Witherspoon and the rest of the administration. However, it is not one that can be easily remedied.

“Schools were designed to be in-person. School is a place where students come together, interact with one another, a place to interact on an academic level, sharing ideas, debating ideas in class, discussing and learning together. School is a social place as well,” Witherspoon says. “We’ve been trying to do everything to make e-learning as much like real school as possible, to compensate for the tradeoffs. So even though we may not be here in person, we must still build relationships. Teachers want to get to know their students in Zoom settings and in Google Classrooms.”

While many teachers are using tools like surveys and breakout rooms to build connections with students, some students have found these spaces awkward and disorienting.

“Breakout rooms hold a very similar place to group work when you’re in a group with people that are best friends, they communicate with each other but not you. With breakout rooms, [however], it’s more of a distinct silence, and because there is no moderator and no definite way to tell what we’ve all been doing, people usually are just off or out,” senior Journee Adams says.

There is no clear way to simulate face-to-face relationships over Zoom. A student can’t talk to the person sitting next to them or engage with people in the hallways. Most students need community for school to be bearable; without it, the work quickly becomes overwhelming.

“I think the virtual experience can fall short when a teenager finds it difficult to reach out for support. I know it’s not always easy to take that initiative and contact a teacher, counselor, dean or social worker. But I do know that no student will go unattended or ignored if a student reaches out. One of the things I would really encourage students to do is to reach out electronically. Take initiative and message your teacher. If you need more contact with your teacher, more relationship building, or need to spend more time with your counselor or social worker, message them. In some cases, it might actually seem a little easier to use email to initiate the contact,” Witherspoon says.

“When you are feeling even a tinge of need—you don’t have to be feeling desperate or terrible—reach out. You might just want someone to talk to. If you feel that you could benefit from more interaction with somebody here at school, send that person an email. I know you will be pleased with how well that goes. The ETHS staff cares about each student, cares deeply.”

While it may be true that students who directly reach out are satisfied with how well it goes, the core issue is that many students are having trouble reaching out to friends, let alone asking for help from adults with whom they haven’t had the chance to form connections. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, illnesses such as depression are characterized by “loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities.”

“I think introducing yourself in breakout rooms or creating group chats for the entire class or even emailing students personally is really difficult… Even keeping up with your friends, texting or calling them, and finding other ways to reach out to people beyond just showing up to a Zoom class without having your camera on has been a struggle,” Jen says.

“I think a lot of people are embarrassed to get help and scared to talk to people,” sophomore Gillian Aaronson said. “Teachers should be giving students more slack because this year is so different; I think school work especially shouldn’t be the priority right now, it should be people’s mental health.”

Enhanced e-learning during a pandemic proves that school work remains a top priority of the administration, creating a reality for students in which school no longer feels meaningful, a reality where, to quote Moskal, “the mental health issues are kind of a never-ending black hole.”

“We’ve been living through one of the hardest portions of American history with the Black Lives Matter protests, the pandemic, all of this mounting to one singular tension point. I think that them narrowing this down to ‘How are you guys feeling?’ doesn’t quite cover it,” senior Callie Stolar says.

“I know they’re scared of getting things wrong, but we’re all going through this for the first time; this is the first time they’re doing e-learning at this capacity,” Moskal says. “No one is going to do it perfectly.”

This tension point, this black hole, is very real. Students are drawing closer to a point of no return, where anxiety, stress and isolation merge into a single construct that threatens countless students; where no matter how hard one tries, the pull of its gravity is too much to overcome.

“Everyone’s hurting on some level. It is a personal experience for literally everyone right now that the social-emotional, mental side of things is equally important to the content. We just have to make sure that the kids are okay mentally, or they’re not going to get a thing from remote learning, and you run the risk of seeing these stats build-up: depression, anxiety, God forbid, increases in suicide,” physics teacher Mark Vondracek says.

Despite this fear, it seems that enhanced e-learning is here to stay, with the administration continuing the push for real, rigorous school in a remote world. There are no perfect solutions in this crisis, only tradeoffs and triages that prioritize some and leave others suffering alone by necessity.

“People are just really scared,” Moskal says. “I think there are just so many overlapping fears that are bundling up into one huge, crazy bundle of fear that people don’t know how to handle.”