Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Nashville in November 2025, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

A call for conscience: the layers of sexism at ETHS

April 26, 2021

In the Classroom

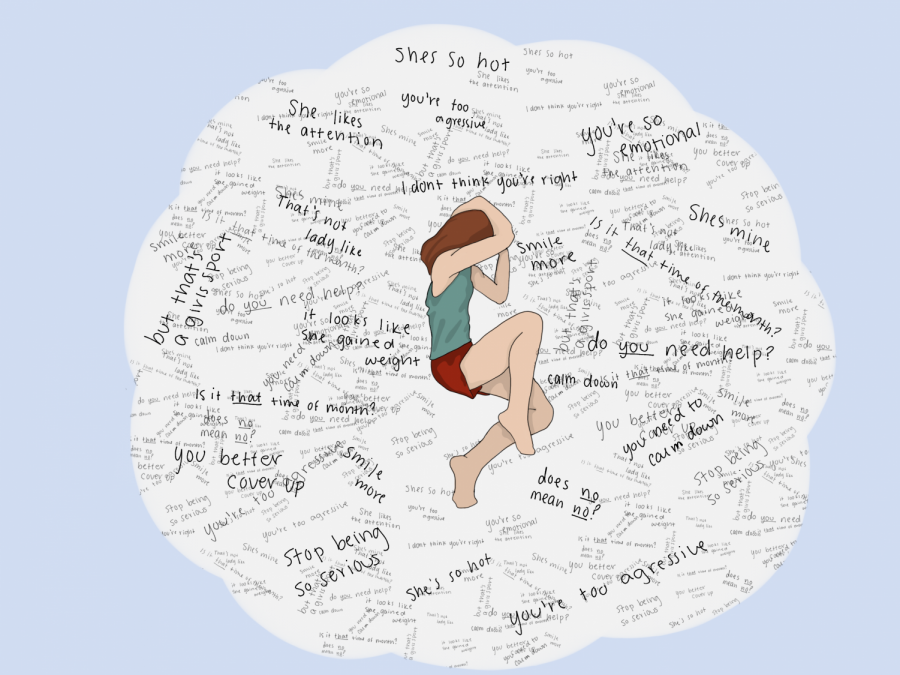

Schools are no exception to the culture of sexual harassment that plagues much of society. As teenagers work to grow into their identities, the culture of sexism and sexual harassment in their communities impedes that progress.

Whether it is whispers in the halls, outright sexist comments in the classroom or an objectionable view of women and their role in the world—sexism is very much alive and well in schools, including ETHS.

Nationwide, rates of sexual violence and assault, particularly within schools, are on the rise. According to a Department of Education report released in October 2020, incidents of sexual violence in K-12 schools increased by 55 percent—from 9,600 cases to 15,000 cases—between 2015 and 2018, with incidents of rape increasing by 99 percent over the same time period. Combined with the fact that around 75 percent of all assaults go unreported—a number likely higher among high schoolers, as only 14 percent of students who have experienced sexual harassment reported it to a teacher or administrator—there is an increasing need to discuss and act to change the culture that leads to these tragedies.

Evanston, despite viewing itself as progressive, is still deeply permeated by bigotry and bias, leaving much work to be done to create a space where all people feel safe, respected and heard; this is certainly true in the case of sexism. While there is more accountability for sexism and sexual harassment now than ever before, there are still far too many excuses made for the reprehensible behavior of boys and men.

“The sexism that occurs at ETHS is casual; it’s a lot of little things. I think it’s pretty similar to the way that a lot of things are expressed at ETHS; we see ourselves as very progressive and above it, so it’s a lot of almost microaggression-type things, with teachers saying, ‘Hey, are there any strong boys who can help me carry these desks?’ and it’s not really a big deal, but it’s just those repeated small little things,” senior Coco Walker says.

“A lot of [our sexism] is [justified by] ‘Boys and their hormones’ and ‘Boys will be boys.’ That’s the excuse. There are a lot of girls at ETHS, there are a lot of people that are vulnerable in those situations, and I think there’s not much that ETHS does that protects victims,” senior Chloe Haack states.

While places like the cafeteria tend to be the most monitored, and while there are adults in the hallways and the classrooms, there are lots of conversations that occur outside the earshot of the authorities meant to handle these insensitive and problematic situations.

“[Students will] make jokes that I always thought were particularly offensive, jokes about sexual assault and just kind of treat it as if it’s not a serious thing,” senior Kate Krasinski says.

As Krasinski mentions, it is not an uncommon habit to hear jokes about issues surrounding consent and sexual assault. A report by the National Education Union of the U.K. corroborates this point, showing that 66 percent of female students in co-ed high schools have experienced or witnessed the use of sexist language in schools; this is contrasted to merely 37 percent of male students. Furthermore, only four percent of women reported the use of sexist language to a teacher.

“I would say, all in all, we’re a little naive when it comes to the struggles of being a girl at ETHS,” Haack details. “I think that’s hard, because, in high school, there’s still this kind of weird [pattern]… guys tend to have a lot more guy friends and girls tend to have a lot more girlfriends. So, I think that a deep understanding of what the other side is going through is definitely still speculated [through] the groups they interact with, and I think that can show.”

One of the daily challenges of which boys may not be aware is the frequency of catcalling. In 2017, ETHS altered its dress code to be more inclusive and to combat many of the sexist implications that stem from strict dress codes. As a result, some female students have experienced a shift in their anxieties associated with apparel.

“I think with [the revised dress code], people are a lot less worried about what they’re wearing and more worried about whether someone will catcall them. Now, it’s less about ‘I might get dress coded’ and more ‘Is someone going to catcall me in the hallway?’ Because we can practically wear whatever we want at this point, the worry about dressing appropriately isn’t there, but now it’s heightened to worrying about what other people think and about being catcalled,” Haack reflects.

Clothing is at the center of this shift, from fear of being dress coded to fear of being catcalled, emphasizing the weaponization of apparel towards girls and women. Regardless of rules referencing clothing standards, female students continue to encounter obstacles in terms of how they choose to dress.

“I know a lot of my female-identifying friends have experienced sexual harassment in the halls as well as textbook misogyny in the classroom, [such as] men speaking over women, dismissing or scoffing at ideas that female students raise [and] objectifying their peers,” senior Lara-Nour Walton says.

Another challenge facing students is that, when a sexist incident or remark occurs, very few report it to the school administration. As the previously mentioned National Education Union’s 2017 report on sexism suggests, only 14 percent of students who have experienced sexual harassment reported it to a teacher. Equally important is the fact that “78 percent of secondary school students are unsure or not aware of the existence of any policies and practices in their school-related to preventing sexism,” and, of those 22 percent of students that are aware, only 40 percent think they are effective. In total, only 17 percent of female students believe that their school does enough to stop sexism and only 22 percent believe that it is taken seriously.

“In terms of stigma and barriers, I definitely believe that that exists… We’ve worked hard [to end the stigma],” Associate Principal of Student Services Taya Kinzie says in an interview with the Evanstonian.

“The environment at ETHS makes it that: you don’t say anything, nothing happens to the kid or teacher that did it, we have to play it off as normal. And that’s not okay,” Haack says.

“I haven’t [reached out to staff]. I know some of my friends have reached out to staff members about this,” Walker says. “The administration doesn’t seem to be taking any steps about it when most of the girls I know at ETHS would say that’s the case and have experienced something weird.”

In the Lab

Beyond what can be easily seen, sexism can lie in deeper areas. The systemic effects of centuries of gender inequity have led some students to feel inferior to their male peers. While it is less explicit than catcalling and discrimination based on appearance, academic insecurity is as much an aspect of sexism as overt harassment in the hallways.

“I was so intimidated by the guys in the class. I never wanted to get called on. I didn’t want to be in a group with the guys, and I didn’t have that at all with the girls,” junior Lindsey Jacobs says. “I feel like that’s very complicated, tying that back to sexism, but I definitely think that there’s that aspect. It’s kind of like academic intimidation I’ve experienced throughout my academic career.”

“[The culture] definitely does make it a little more ‘Make sure you think before you speak,’ just little pauses because you feel like you need to prove yourself more if you’re being held to these standards,” Walker says.

Sexism is particularly prominent in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) courses, due to the long-standing male domination of those spaces.

“Personally, the only time that I felt—I wouldn’t say discriminated against—but I felt some sexism was in the STEM classes I’m in. I’m in Chem/Phys, and then this year, I’m in computer science, and there are just not as many girls there. There are five girls in my class, and being in breakout rooms, I feel like sometimes the boys in my class will shut down the ideas of girls or they won’t be as flexible to hearing what we have to say, which I think is a problem that exists in STEM overall,” senior Ana Sweeney says.

This is far from an isolated case, as STEM fields have long been held as male-oriented careers. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, women make up only 28 percent of the STEM workforce, with career pathways such as math and computer science being 74.2 percent male and engineering being 84.3 percent male.

“I’ve been in a lot of male-dominated spaces, especially in the math and science range, and in male-dominated clubs. I’m [particularly] thinking of Math Team; there aren’t that many girls in it right now, but there was a certain period of time when I was one of three girls coming to meetings, and it just was not a very good environment,” senior Emily Hauser says.

The gender gap in STEM leads to some of the largest salary gaps, as STEM workers earn two-thirds more than those employed in other fields (according to PEW Research Center). Men in STEM earn, on average, $15,000 more per year than women, with Black and Latina women earning $33,000 less per year. Even STEM careers with more female representation, such as health care and biology, only 21 percent of executives and 33 percent of doctors are women, with most found in lower-paying fields such as home health work, nursing and pediatrics.

According to the American Association of University Women, the chief causes perpetuating these disparities are gender stereotypes—particularly surrounding math and math anxiety—fewer role models and male-led cultures.

“I guess it’s just how racism and sexism works, that white men just feel like their opinions and voices are more valuable than others, especially in math and science classes. I think that’s because there’s a lack of people of color and a lack of women who are in STEM classes, which is another thing. Maybe they just feel more comfortable in the environment,” junior Taryn Robinson adds.

Robinson notes that these stereotypes related to math and science affect the self-esteem of students in the class environment. However, annual student achievement data collected by ETHS in 2020 indicates that, for every identity group surveyed, the percentage of female students who excel in math classes is greater than their male peers.

The data, which is separated by race and gender, still shows that, for the core subjects of STEM and Language Arts, white students often have higher achievement rates. These findings relate back to Robinson’s comments on the connection between racism and sexism in her classes.

“I think [the school] can do better, and I know we can’t really do anything about class demographics because that kind of relates to what kind of people sign up for what kind of class, but, at the same time, that connects back to self-esteem. If you are in higher-level math, for example, where you just don’t feel as smart as the other people because they just answer the questions a lot, and most of the time they’re male and white, then maybe you might not decide to sign up for the continuing class,” Robinson says.

The impacts of racism in education are systemic. The structure of classes and a history of oppression within education have hindered the student achievement of students of color. The school has made efforts to combat this issue, but it remains prevalent at ETHS. When racism and sexism intersect, a classroom can feel isolating for students.

“I do think it is important for people to share their opinions, but it’s just that white men in particular, I have seen in classes and in life, can put their opinion above others,” says Robinson.

Male superiority is something that women, especially in STEM classes, often face. Whether intentional or not, sexist stereotypes can cause women difficulty in the classroom.

“I’ve experienced this feeling of both being singled out as a woman for being too outgoing and caring too much about getting things done and then, at the same time, just not being listened to at all and not being taken seriously,” Hauser says.

There have been efforts by ETHS to remedy these cultures, including starting Women in Engineering, Women in Programming and Women’s Economics courses. However, this solution focuses on separating genders for a more equitable class rather than tackling the issue of a male-dominant culture.

“I guess you could see pluses and minuses to the class. I signed up to take [the] women in economics class because I wanted to take economics, but I knew that if I took the regular economics class, it would be difficult,” Robinson says. “I don’t want to say that I fully support [the class], and I don’t want to say that I fully don’t support it. It’s making spaces available for female collaboration, where our voices can be heard. There are positives in that, because a lot of the time in classes and in clubs, you don’t have that opportunity because of the dominating male voices.”

Similar attempts to provide spaces for women in STEM have been made in clubs. Some STEM-based extracurriculars, such as Girls Who Code and Health Occupations Students of America (HOSA), are open to all students, but the demographics remain primarily female. Club members notice the lack of non-female-identifying voices in the club and are working to address the discrepancy.

“Our whole club [HOSA] is mostly girls. I think that we only had one male-identifying student qualify for state, and there are only a few other boys in the club. It’s weird because we have sexism [in STEM], but then we also have a lot of girls in the club. We’re trying to incorporate more genders into our club and make it a more welcoming space,” Sweeney says.

While these efforts may have had some success, they don’t interrogate the larger issue at hand, as they don’t work to challenge male-dominated spaces but rather provide alternatives. Sweeney says that separating the clubs into “for girls only” is another form of gender sexism. It can also lead to the belief that there are certain STEM pathways that are better for women than others.

“I feel like, in health and biology, there’s been a big push for a woman to be in STEM, but often, it’s women in health, not women in physics,” Sweeney says.

Another aspect of the STEM culture is the feeling that concerns over sexist behaviors aren’t of enough importance to reveal; a feeling reported by both Sweeney and Hauser.

“There’s an element of feeling like it’s not significant enough to share and to call out—not that it isn’t—I do think and I believe that it is significant—but not trusting yourself and saying, ‘Oh, I shouldn’t bother someone with this. It’s not important. It’s not relevant,’” Hauser says.

“There’s also a little factor of shame, feeling like I should just be able to deal with this. I had a pretty bad experience in Chem/Phys one time… with a taunting type spell; like it was [a] middle school, very boys-versus-girl situation. I considered talking to the [teacher] that day because this was substantial—it’s a problem, I felt very uncomfortable. Now that I’m reflecting on it, I didn’t want to burden people with it, and that’s just what it’s like to be a woman in a space like that; that’s just what I have to learn to live with.”

“I haven’t ever said anything [about class culture] personally, but with female teachers, it tends to be more of a comfortable environment. In my math classes, sophomore and junior year, I had female math teachers, so I feel like they wouldn’t put up with the kind of stuff that a male teacher would put up with or not even realize was happening. I had more of a voice in those classes; I felt more comfortable,” Sweeney says.

“I definitely want to [call sexism out] in the future, especially in college. I’m going to major in physics, so I definitely want to focus on that and bring it up with other people.”

In the Gym

With regards to Physical Education (P.E.), the required freshman and sophomore courses are the classes at ETHS which provide students the most information about their sexual health and wellbeing. When taking on such a monumental task of teaching 9th and 10th graders about topics of sex-ed, consent and healthy relationships, there inevitably will be choices made regarding what to feature in the curriculum.

The Evanstonian has previously published a variety of student opinions about the P.E. curriculum, including gender-exclusive classes, insensitivity in Rape Aggression Defense (RAD) self-defense program and the non-inclusive swimming curriculum.

The freshman P.E. classes are separated into male and female classes, where each class spends roughly four weeks covering a variety of healthy relationship topics. This includes sexual assault, harassment, sexual education and self-defense. How those topics are covered and for how long often differs based on the gender of those in the classes.

Girls’ freshman P.E. teacher Luella Gesky believes that there are benefits to the separated classes, especially when attempting to inform students about an abundance of content in a short amount of time.

“I think that the male and female students should be taught differently because of the time limitations on how deep we get to go on the topic,” Gesky says. “The most important and the most relevant information to that [gender] is able to be taught. By having them separate, you can teach more relevant information.”

Although some teachers see the differences as positive, there is no debate that genders get distinctly different messaging. For instance, girls’ classes spend the self-defense unit following the RAD curriculum, while a less strict format is made for boys’ classes.

A complaint expressed by many female students is how, from their perspectives, when classes are separated by male- and female-identifying students, it appears the boys’ P.E. classes do not take these topics as seriously and simply gloss over self-defense and consent units because it is seen as less important to them.

Outside of self-defense, freshman P.E. begins to inform students on consent and starts discussions about healthy relationships. Freshman boys’ P.E. teacher Chris D’Amato explains the importance of teaching consent.

“[Consent is a] conscious conversation that occurs between two people, where they both acknowledge what is going on, and they both kind of understand that the conversation is basically taking place and acknowledging that no means no, [which] I think is one of the most important messages.”

Sophomore Wellness and Junior Leadership teacher Montell Willburn believes that the Wellness curriculum provides more space for the topic of consent than the freshman P.E. curriculum does.

“I don’t know much about freshmen P.E. and what they teach for consent. I do know that their unit is two weeks long, and I don’t think it’s as in-depth, and it covers multiple topics. I think consent is one of them, but I don’t think they go as in-depth as we go for Wellness.”

Some students feel that the freshman course wasn’t as effective in teaching them the meaning of consent and preferred what was taught in sophomore Wellness, where more time is being specifically diverted to covering healthy relationships.

Sophomore Blythe Coleman says, “We were taught that, in a healthy relationship, trust and communication needs to be present in order for it to be mutually beneficial. I really like how they went in-depth with this part and how they established that trust was necessary.”

Since Wellness education is a semester-long, co-ed, course, teachers have the ability to dive deeper into teaching the healthy relationships unit along with sex-ed. However, students believe certain topics are not being given the attention they deserve, one of which being consent.

“In my personal experience, I don’t think consent was taught as well as it could’ve been in the Wellness unit. If we were taught it, which I can’t remember if my teacher did or not, I know for sure it was not as extensive as it should’ve been,” Coleman says.

Sophomore Moxie Dully agrees with Coleman that, similar to the freshman P.E. courses, the Wellness curriculum also lacks inadequately addressing all angles of consent during the Healthy Relationships Unit.

“Consent was maybe brought up a little bit, but nothing about gender or consent was ever talked about in-depth,” Dully adds, “I think that it is definitely harmful that we’re not talking about it enough, because it is such a big part of our lives: consent, gender equity. It’s just something that, as high schoolers, we’re learning about, and it shouldn’t have to be all on our own.”

Coleman elaborates, saying, despite the emphasis on women’s health, the topic of sexism—an issue that affects many women—is missing from the curriculum.

“I think sexism is somewhat grazed over in the Wellness unit, and it is not integrated well into the topics that we learned about. We are mainly only taught about female contraceptives and what the females can do to prevent pregnancy,” Coleman says.

In addition to addressing a topic like sexism, intersectionality plays a fundamental role in understanding consent. The way in which gender interacts with sexuality is often overlooked in these class conversations, another issue that has been raised by Haack.

“In Wellness, I learned nothing about being gay. I’m gay, so having that experience of heteronormativity being pushed of consent [being] between a man and a woman [wasn’t great]. An example [of what could be done] might have two girls or two guys, or someone whose non-binary, but does [Wellness] really go into the queer-specific topics? Absolutely not,” Haack says. “I think there’s a lot that could come with [teaching the queer experience], and I’m not saying that we segregate straight people and queer people in Wellness, but the least I would hope is that I would get some education on what it’s like to be someone whose gay in the real world. I feel like I’m totally missing that, and I shouldn’t have to resort to using the internet to answer my questions. When you find out you’re gay, you wonder ‘What do I do now,’ I think that’s missing from the Wellness and freshman health classes in ETHS.”

While students conceptualize an experience in which topics like sexism, gender and sexuality are at the forefront of their learning, freshman P.E. teachers highlight the benefits of single-gender class structures.

The way that females and males experience the world, and our considerations when it comes to the issue of consent, are different. Statistically, about 99 percent of sexual assaults are perpetrated by males. When you teach about sexual assault, or when you teach consent to males, that there is a certain perspective that needs to be addressed, and that is more stressed. When it comes to teaching females, there’s a different perspective. So I think it is useful to [have] homogenous classes,” Gesky notes.

The difficulty freshman teachers face is comprehensively teaching the topic in the restricted time frame.

“It’s hard because the P.E. curriculum for consent is something that we cover in two-to-three days. The conversation around consent can never be covered too much. You can always use more conversations about it,” D’Amato says.

Neither class can give the necessary time to discuss consent and sexism. In addition, part of the issue with the overall class can be attributed to student behavior. Even if discussions regarding healthy relationships and consent are being brought up in Wellness classes, there are students who are not taking advantage of the information.

“Frankly, I don’t think that these discussions [on consent and sexual harassment] change anything in terms of the environment at ETHS. Because you see mostly older kids catcalling; people that have already taken Wellness and have learned that that’s wrong, yet they do it, and I think that’s further evidence that Wellness, as much as it might help one student in the class, there are other people that are missing out because they’re not paying attention and are trying to get through [the class],” Haack says.

However, regardless of the acknowledgment that not all students are being responsive to the information provided, there appears to be student consensus that mandatory health classes in high school are necessary and important. The issue lies in whether the current freshman P.E and sophomore Wellness classes offer the best information to all.

“I do think that there are some aspects that are being glossed over. We never had a discussion about racism, we never had a discussion about gender dysphoria, or body dysmorphia or sexism…. There’s a lot of good things that we are talking about, but there are many, many things that I feel like are being ignored because they don’t want to add it to the curriculum,” Dully says.

While criticisms have been made—specifically from students—about the P.E curriculum, Kinzie, whose department works with P.E. to incorporate lessons surrounding mental health and sexual assault, says she hasn’t heard much push-back from the greater Evanston community.

She says this is due to the critical work done by the P.E. and Wellness department to ensure transparent communication between students and staff, as well as the administration and P.E. department being receptive to students’ opinions on the curriculum.

“We’ve been fortunate,” Kinzie says. “I think everybody’s been intentional to think about how are we supporting and how are we navigating this information together. There’s no hidden agenda. Everybody’s very direct about it, and I think we’ve been very fortunate to have that level of support and to connect that to what’s happening in the larger school, in the hallways and outside of the classroom environment…. I think our P.E. and Wellness team has been great about saying, ‘Hey, this is going to be coming up.’”

It appears that the department is aware of changes it needs to make on various fronts, but the implementation of a new curriculum and tackling insensitive teaching techniques has yet to be done.

“I think if I knew some ways that it could be better, then I [would] be working with my team to try and make it better. So right now, I think it’s as good as what we can do,” Gesky says.

In Extracurriculars

Sexism extends far beyond the classroom, permeating every aspect of ETHS and the many communities within it; this includes the many clubs and extracurriculars offered by the school.

“In DECA, not specifically at ETHS, but just in DECA, I would say that there’s definitely always more men involved in the club; that’s just something that happens,” senior Zoe Cvetas says. “There’s an event called sports marketing, and it’s always men. Two of my friends, they were both girls, competed, and they were the only girls in that event…. But I would say there are actually more girls in the ETHS club than guys.”

The fact, that girls make up larger percentages of clubs than boys, applies beyond just DECA. At ETHS, 77 percent of women participate in extracurriculars (athletics, fine arts, activities) as compared to 69 percent of men. In addition, 46 percent of female students engage in clubs, fine arts and athletics compared to only 25 percent of men.

“I think that there’s a pressure on women and girls to constantly be proving themselves to do more, to show why you’re deserving; that definitely shows up in clubs,” Jacobs explains. “I’m not saying that everything we do is just because we’re trying to prove ourselves…. When I look at the women around me, inside and outside of school, I see so much drive and passion in a variety of interests and care about things bigger than themselves, and not to say that there are no guys that have that, because that’s absolutely not true, but when I look at a lot of guys around me, I don’t see that. I see the stereotype of them playing sports and hanging out with their friends.”

As Jacobs explains, the sheer fact that more women are involved in an activity does not remove it from the systems of sexism it was built within, particularly if a sharp gender disparity in involvement forms.

“I definitely think that if we had more male leadership, which we really don’t have, that would help raise the male population in the club as a whole. Everyone looks to the leadership as the example of who this club is, and, if they don’t see [themselves], they don’t really think it’s their place,” Jacobs says.

“[In Mock Trial,] all of our attorneys are women; we’re pretty much a female-dominated team. When we went up against schools—10 of us competed at state—only two of us identified as male, and they played witnesses. They’re awesome and amazing, but our whole team of attorneys is female… It’s a little cool to see that we are a team of powerful women, and I tell them that all the time,” Hansen says.

However, despite the demographics within many ETHS activities, cultures and attitudes of sexism still, penetrate these organizations.

“Within the ETHS [speech] team, it’s very female-dominated, so I don’t feel like I’ve experienced a ton of sexism in the team. However, I have experienced sexism and racism on the national circuit,” Walton says. “I’ve always been ranked better by female judges, particularly female judges of color; men tend to rank me lower for some reason.”

“A few years back, we had someone leave the debate and come to speech. They did this because they were fed up with the sexism on the Lincoln-Douglas team and the national circuit. They used the speech as an outlet to articulate their disillusionment with high school debate. Their original oratory focused on the problems in high school debate: the alienation of women on the circuit and rampant misogyny.”

The same theme of women receiving different treatment than men is also seen within Mock Trial, where powerful women are beaten down by judges who would applaud men for the same actions.

“One instance that comes to mind was my sophomore year, my friend was doing a closing argument. This is the first time she’d ever done a closing argument. She’s a very feisty person, and she will go all-in on something. It was our first competition, the judge was female and the jurors who were scoring us, all three, were male.” Hansen adds, “she kind of came out of the gate a little feisty, as you would if you’re giving a closing argument. When we were getting our notes, all the male jurors went first, and they kind of told her that it was a little much, you might have wanted to tone that down, and the female judge interrupted them and she said, no, she thought that was wonderful. I thought that was great. I thought that was powerful. If she was a guy, those jurors would have said that they really loved it.”

On the Field

Within ETHS, there exists a perception that women’s sports are not taken as seriously as men’s. The result is that many female athletes at ETHS feel as though they are viewed as less important than male athletes. Athletic Director Chris Livatino acknowledges this culture, adding that while it appears in ETHS, sexism in sports is nothing new.

“I think we still, as a society, and as a country, as a community, have some ways to go in trying to get people to recognize that female athletes are putting just as much blood, sweat, tears and effort into their sport as our male athletes and that it matters just as much to them,” Livatino says. “I think sometimes that’s the perception, that maybe some people take it as, oh, it’s a fun and nice game for [the girls] but this is like a real sport for the guys.”

It is especially upsetting to female athletes who not only want to be considered equal to their male peers but also be treated fairly. Junior Dystonae Clark, notices a lack of respect given to her sport and in most female sports at ETHS.

“I think the boys’ team does get a lot of recognition like the school just respects them more. I don’t really think it’s just [my sport], but I think girls’ sports, in general, have just been kind of pushed to the side,” Clark adds. “It’s really sad when you’re putting in so much work and sometimes we do put in a lot more work than the boys’ team or will like to accomplish more than they have. But just to see it like being looked at as if we’re not doing as much, just because we were females, is sad.”

Even if female athletes put in more time and effort, there is always a double standard by which they are judged. Clark expresses how female athletes are held to different expectations than their male peers. One of the ways this disparity is demonstrated is within uniforms.

“The boys can practice without shirts; they can [workout] in shorts or whatever, but not with us. I remember the first time I came [to practice], I wore Nike running shorts, and they told me we had to wear leggings. So I had heard that it’s because the boys were there, but they didn’t really give me a reason why,” Clark adds. “ So it’s kind of weird to see how we have to do all of that, but for the boys, it’s not a requirement to do that.”

Having to adapt uniforms is both an inconvenience to women and an apparent difference in the treatment of athletes. Additionally, the critique of clothing or body image is often an unwelcome experience to which female athletes are subject.

“I’ve been the witness of a lot of body shaming in sports, and that’s so tough to see because that team atmosphere is supposed to be a safe space, and then when [your male coach] is yelling at you, maybe because you’re a little overweight, that [safe space] doesn’t even matter,” says Haack.

Students have stated how there are differences in how secure the sports environment is with female coaches compared to male coaches.

“I’ve had coaches at ETHS that have mostly been female, and I think that’s really good for us, but the times that we’ve had male coaches, there’s a bit of that discomfort there,” expresses Haack.

Dealing with a situation that makes an athlete feel uncomfortable can be extremely difficult. Often, an athlete will not share their experience with a coach or staff member because they do not feel supported by the department.

In order to address this stigma, the athletics department has attempted to provide more resources for coaches to analyze their interactions with athletes.

“We actually had a whole professional development seminar for our head coaches on the topic of consensual sex, and helping them understand what that was,” says Livatino, in regard to a seminar, provided three years ago to primarily male coaches about sexual assault awareness and gender equity.

“We have some older coaches that come from a different era and don’t necessarily understand how, saying to a female, we can’t have you wear that because it’s not ladylike, how that just isn’t something that society today is okay with,” adds Livatino.

The professional development seminar was intended to educate coaches on how to interact and communicate with athletes, to be aware of how they treat female athletes, as well as how to have their own conversations with male athletes on the importance of understanding consent. In addition to the seminars for coaches, the spring pep rally in 2018 was dedicated to spreading awareness of sexual assault.

The Athletics department has made strides to combat sexism within ETHS sports, but the culture still remains. Seminars and pep rallies serve as momentary solutions to the systemic issues of a lack of understanding consent and the existence of sexist institutions within athletics.

Krasinksi notes that she doesn’t recall an instance where sexism and consent were addressed in her sport. “I don’t remember ever hearing about anything, and maybe for specific sports that I don’t participate in, but I feel like, as a whole, there’s not really any emphasis on conversations about sexism.”

Continuing the training for male coaches and offering more support to athletes are some of the ways the school can follow through on its goal of creating a safe environment for all players. Haack expresses that the Athletics Department should put more emphasis on addressing consent since it is crucial for both students and coaches to understand.

“Maybe there would be more understanding overall when it comes to making sure everyone is okay with what you’re doing. Because making sure what you’re doing is appropriate is having a conscience and making sure you are doing the right thing, and I think that happens in a lot of scenarios, and that’s something that would be nice to be brought into sports because making sure that everything’s all good with your players is a big part of [consent] too,” says Haack.

As demonstrated throughout culture, academics, P.E. and Wellness curriculums, clubs and sports, sexism has managed to infiltrate the various components that construct ETHS. With the intersection of these collective elements, navigating a high school setting as a female-identifying student is inherently riddled with adversity. As in-person instruction begins to return, female students are obligated to confront aspects of a misogynistic culture that were temporarily alleviated as a result of remote learning.

Although immediate modification to systemic and societal sexism is unrealistic, a dimension of understanding towards the challenges of female students is not only plausible but impactful. Observation of sexist subtleties, in combination with intervention, is a constructive method of challenging institutionalized misogyny. To work towards a safe atmosphere for all ETHS community members, recognizing gender-based discrimination is essential. Through furthering the conversation, policies and programs in all areas of ETHS, the sexist environment, which has long been upheld, can be dismantled.

Vivien Bissell • Apr 27, 2021 at 9:58 pm

I wouldnt say that just because teachers are male means that they cause discomfort, speaking as a girl. it shouldnt matter.