Stress and substances: the supports in place for students in Evanston

Teenagers are living in an entirely different reality. Despite sarcastic connotations that may frequently accompany that phrase, research suggests that it may be true in some ways. Dopamine, sometimes referred to as the “pleasure chemical,” is a mood-enhancing chemical in the brain that influences various aspects of one’s everyday functioning—including judgment, motivation and attitude. Dopamine is released when the brain anticipates or receives some kind of reward. Research indicates that baseline dopamine levels are lower during adolescence, but in turn, the chemical is released much more. As this neurological reward system intensifies in teenagers, their susceptibility to risk-taking and addiction does the same.

When humans indulge in thrilling behavior, the brain releases dopamine and other chemicals as a protective response. Consequently, teenagers are driven to seek out exciting, risky and experimental activities. This information helps to explain why, in a 2018 study conducted by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, it was found that 164.8 million people aged 12 or older in the United States had reportedly used a substance (tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs, etc…) in the past month. Aside from gravitation towards experimentation, various other causes behind teenage substance use exist as well.

“There’s a lot of reasons why kids use substances, and it could stem from trauma, it could stem from low self esteem, it could stem from mental health [struggles], and it really could just stem from boredom. Boredom is a big one,” explains Kaylaa McGinnis, a Community Relations Coordinator at Rosecrance, an organization with over 60 behavioral health treatment centers in the Midwest.

When analyzing the different reasons why teenagers may use substances, it is essential to consider the external factors that influence decision-making. A central force that can play a role in adolescent drug experimentation is school-related pressure.

“We have a lot of kids in high pressure schools … They [feel like they] have to get an A plus plus plus and get a 5.0 [grade point average, which] doesn’t exist, so they’ll start to utilize stimulants, maybe cocaine, things of that nature,” McGinnis expounds, going on to describe a different type of pressure teens may face, “Some [teenagers start using substances due to] peer pressure; they’re underclassmen, and they want to fit in. They’re at a party, and someone’s drinking beer, and they don’t want to be the guy that doesn’t do it. [Let’s say] Johnny’s drinking a beer, and it works for him. It makes him social, and all of a sudden, he is funny. He liked that attention, [so] next week, he’s doing the same thing and the following week, the same thing.”

Hyperrationality refers to the tendency of placing a greater significance on the positive outcomes of a certain action as opposed to the potential risks. Hyperrationality is more frequent in teenagers due to the structure and functioning of their developing brains and is exacerbated by the presumption that a teen’s peers are monitoring their actions. As reported by Centerstone, a non-profit organization that provides mental health and substance use disorder treatment to over 140,000 people each year, about 90 percent of teenagers have reported enduring some form of peer pressure, a statistic that undoubtedly includes some pressure to use illegal substances.

Regardless of what may drive adolescents to begin using substances, this age group is much more vulnerable to addiction as a result of increased dopamine production that occurs during adolescence; the same dopamine production that enhances the likelihood of risky behavior. With the use of an addictive drug, a surge of dopamine is released in the brain. However, when that drug is no longer in effect, dopamine levels plummet. As a result, the brain begins to crave this surge of dopamine again, which can create an addictive pattern of substance use. Since teenagers produce more dopamine on average, an adolescent’s brain is more likely to develop addictive behavior. As such, recognizing the risks of addiction early on is vital for the prevention of dangerous behavior.

“Most people who experiment with occasional cannabis use or alcohol are not going to go on to develop a substance use disorder. There’s kind of two pathways that happen. [The first one is] someone who has no risk factors, no family history, no genetic kind of contribution, no childhood trauma. They’re experimenting, a little partying with their friends, but they’re keeping up with their grades, they’re still socializing [and] they don’t have significant other mental health issues. Most of them grow out of it, [either] after college or before,” describes Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral science at University of California, Los Angeles Dr. Kate Wolitzky-Taylor. “But, there is a sizable percentage [where that isn’t the case], so people really need to ask themselves, ‘Do I have any of these risk factors? Because, if I do, I could potentially be setting myself up for a really big problem, and it’s much easier to deal with it now than it would be to deal with it in like 15 years from now.’”

Despite the perceived sensibility of getting help in the early stages of addiction, actually obtaining adequate and appropriate support is much more difficult than it may seem. There is a huge stigma surrounding substance use in teenagers. This stigma is even prevalent in healthcare. It stems from negative feelings held by many people that those struggling with substance use disorders have only themselves to blame for their addiction. When even healthcare professionals believe this huge misconception, it is made extremely difficult for those actually struggling with addiction to find reliable and trustworthy places to get help.

“Students definitely have a fear of being punished, because if you don’t trust your social worker or counselor, then you’re not going to open up and be honest,” says Wellness Education teacher at ETHS, Montell Wilburn.

Trust is the biggest factor in a successful recovery, Wilburn and others suggest. If one does not trust the help they are getting, then the recovery will not be successful. Working to dismantle the stigma around addiction and substance abuse is the best way for students to gain trust in authority figures around them so they may reach out for help.

“Breaking that stigma…isn’t something that happens instantaneously, so when we take action to normalize [seeking] out help for mental health, small little actions can create big change…I think outside of Evanston, it’s becoming a little destigmatized, but that change is gradual. It won’t happen overnight, but we’re making some progress.” Wilburn asserts.

Mental health has long been a sensitive subject, with adults and teens alike dodging discussions about its harsh reality. Experts and organizations, such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Adminstration, agree that drug abuse is, and always has been, a disease. It is not the fault of the user, but of the drug, designed to addict. The more that this message can be spread, the easier, safer and more comfortable students will be to reach out for help when they feel unsafe with their substance usage. If work is not put in to change society’s perception of drug use to one that acknowledges the difficulties of dealing with addiction as opposed to placing blame, young adults will never feel good about seeking help. A culture that perpetuates this stigma is a culture that is actively harming teens, whose brains are hardwired to experiment and who need easy access to non-judgemental, knowledgeable resources who can help them overcome their substance issues.

“I used to have this mentality that, if I’m dealing with something, I can handle it myself,” Wilburn recalls. “It was kind of toxic, but that’s what type of mentality I had until recently. I can’t remember what specifically, but when I was dealing with [personal issues], I normalized going to visit my psychologist. It feels normal to me; it doesn’t feel like I’m weak for doing it, it feels like I’m stronger…Maybe because of what I teach in wellness, and I’m exposed to so many different organizations and so much information about prioritizing mental health, it’s normal. It has helped me, and it has helped my students, because they know that it’s okay to seek out help and to not handle problems alone.”

The more that students have positive associations with getting help, the better off they will be. Stigmas, such as this one around drug usage in young adults, are deeply rooted throughout generations and cannot be dismantled overnight. It takes energy, time and commitment to change a culture, but it is worth it. Otherwise, young people will feel more inclined to continue on with risky behaviors, putting themselves and their peers in unnecessary danger.

ETHS’ substance abuse supports:

Teenagers undergo a lot, especially during this current moment that added a pandemic on top of the regular stresses of student life. One cannot experience modern teenagehood without endless feelings of stress—either from academia, peers, social culture or personal-self. According to the American Institute of Stress, “Gen Z has higher levels of stress compared to other age groups” and “34 percent of students” anticipate their anxiety will worsen in coming years, reports the American Psychological Association. As young people find themselves increasingly more derailed by stress, some may resort to poor coping mechanisms, including substance use.

At ETHS, this fact is not unknown.

“Student mental health [is] the underlying factor of why people abuse drugs. . . People use drugs for several reasons, [but] all of [those reasons relate back] to stress,” says Wilburn.

To confront this reality, ETHS requires all students during their sophomore year Wellness class to take the Drug Education Unit. The course proactively engages teens in drug and addiction content, attempting to show students the destructive consequences of substance abuse.

“[The Wellness teachers] use a document called the Science of Addiction, which guides the curriculum; from there, we focus on the science of why people abuse drugs. We really focus on marijuana, nicotine, vaping, prescription drug[s], alcohol and cocaine,” says Wilburn. “We talk about basic information about [each of the] drugs but [also] explain [that] the underlying factors of why people abuse drugs is stress management. [We explain] how [some students] destructively cope with stress by using drugs.”

Crucial to the Drug Education Unit is transparency and vulnerability. Wilburn acknowledges the success of the class depends on students’ comfortability discussing the personal subject matter. To foster a sense of community, Wilburn often shares experiences of his own to his classes.

“October 9, 1989. [It’s] a day I’ll never forget. That’s the day [I] found out my cousin overdosed on heroin and died.” Wilburn proceeds to share that several of his family members have an adverse relationship with substances, “My cousins have been in and out of prison for selling drugs, a lot of my uncles abuse drugs, I have cousins who are functioning alcoholics. Drugs in general have definitely affected my life and the people around me, and I share some of those stories with my students. . . [because] I want [them] to find better ways to cope.”

In addition to sharing stories, Wilburn has incorporated what he calls “the universal language of music” to transform students’ understanding of substance abuse. In his class, students are tasked with writing and performing a “drug rap,” in which students parody popular songs and tweak the lyrics to discuss the repercussions of substance abuse.

“I think a lot of them respond well to [the drug rap]. There’s something about music that really does it. There’s an emotional connection … because I have my former students send me emails about how they still remember that song, and their rap or their verse from their song. So it definitely has a greater impact on students, whether they remember what retention of content is, it’s important because they can listen to the song and they can recall the song in their head.”

Paired with informative classes, like the Drug Education Unit, is treatment—an incredibly important component in tackling substance abuse. Within ETHS and the Evanston community, there are several places teens can reach out to if they identify that they are struggling with substance use.

The most approachable support within the school begins with accessing the ETHS mental health staff.

According to the ETHS website, “[The] mental health staff [includes] social workers, psychologists and counselors [who] are committed to continuing providing mental health services to students [whether in-person or online].”

Social workers are assigned based on students’ grade level and can be contacted by parents either by calling the Social Work Office, 847-424-7230 or by calling their student’s social worker directly. Social workers specialize in “providing services for students who receive special education services, students in need of assistance with substance prevention and intervention, students who are expectant parents or parenting and students returning from hospitalization,” according to the ETHS website.

Psychologists are also assigned based on students’ grade level and can be contacted by visiting the ETHS Student Services webpage. Psychologists differ from social workers in that they deal specifically with student mental health challenges.

Counselors are the third component to ETHS’s mental health staff. Although counselors typically deal with nurturing students’ transcripts and post secondary plans, they can be a useful resource if students need help. Counselors can be located via phone call, email or by visiting E125.

Outside of ETHS, teens can reach out to We for Wellness, an ask-me-anything provided by a subcommittee of the Evanston Mental Health Taskforce. We for Wellness provides a supportive and confidential space for discussions and questions about mental health and substance use. The column provides a space for teens to ask questions, gain useful information and connect to resources.

The AMA lists several spaces that teens can reach out to for help such as health clinics, family doctors or primary care physicians, local mental health organizations such as the Evanston Care Network. There are also free online resources like the Crisis Text Line (text HOME to 741741), the National Suicide Prevention Helpline (800-273-8255) and free quitting resources like This is Quitting (text DITCHVAPE to 88709). “And remember, if there is ever a situation where you are worried for your safety, reach out to a trusted adult who can help, or call 911,” one past response read.

Another option outside of ETHS is PEER Services. PEER Services is a program that provides the Northshore with drug and alcohol treatment and prevention services.

“We offer services ranging from a comprehensive medication assisted treatment program for opioid addiction and withdrawal, intensive outpatient services that include therapeutic services and also support and education based services. Our prevention team also provides a range of services to different populations in Evanston free of cost,” explains prevention specialist Ria Kataria. “We are a non-profit organization with a sliding scale payment, which means that people without means to pay are still given an opportunity to seek treatment,” she says.

Kataria describes the process of how to contact a representative from PEER Services.

“A first step to starting a journey with PEER is to definitely reach out with a phone call. After [teens] leave their name and phone number, a member of our adult and adolescent team will call them back and chat with them about the process. Teens also start working with us through school referrals or their parents reaching out first. We then bring in the student for an evaluation and see if they could benefit from services. We might recommend a few sessions of early intervention counseling or long-term individual counseling [if they need it]. . . We do offer both in person and telehealth counseling services currently to make things as accessible as possible,” she says.

Teens or parents can email the PEER services prevention team at [email protected].

Although several supports exist within Evanston, people who struggle with addiction have a long-standing history of inaccess to the help they need.

“On average … 10 percent of those people [who need treatment for substance use] actually engage in treatment. That’s a very, very, very low number,” shares McGinnis.

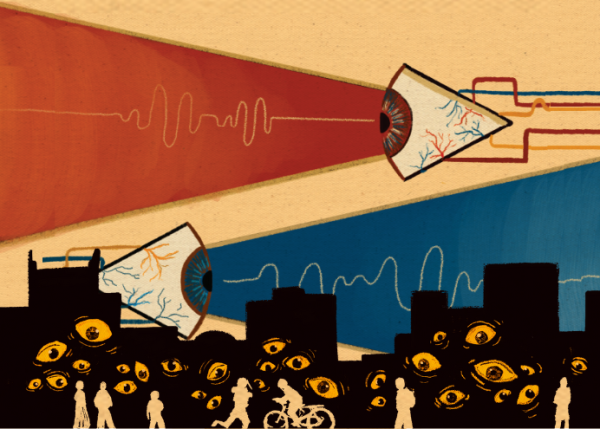

One reason why adolescents may not receive the help they require is because students may feel deterred from accessing these supports due to stigma. Kataria believes the stigma is a by-product of how normalized addiction is in our society.

“There is a definite stigma around substance use and teen addiction,” Kataria says. “I think it’s because of how addiction is portrayed in communities or social media or on TV. You [also] have massive industries like big tobacco at play trying to get teens hooked onto their products. You also have big pharmacies that benefit greatly out of selling opioids. Drugs and alcohol have become integrated into our social lives [without a full understanding of how dangerous they can be].”

Stigmas surrounding drug use are often deepened by the lack of science with conversations about addiction. Neurological factors and age can play a huge role in addiction but often goes unrecognized in favor of blame.

“A lot of people still don’t know that addiction is a disease that develops in your brain. It’s all the chemistry that does it. That’s still something that is not widely spoken about or widely known, and that definitely leads to more stigma.”

The science behind addiction is complex, especially in teenagers, which can establish widely accepted misunderstandings of substance misuse cases. Dr. Wolitzky-Taylor speaks to some of the nuances of teen addiction and how substance use can manifest differently in their behavior.

“You might have adolescents [struggling with addiction] who are kind of acting out, cutting class, getting into fights [or] being the perpetrators of bullying,” Wolitzky-Taylor explains how people typically identify teens battling addiction. “Then, you also have kids that [may be] on the receiving end or may be experiencing peer victimization [or] marginalization … When you look at the literature, you see that those kinds of experiences also put someone at risk for substance use problems, [because] it’s likely through this pathway, where they start to develop these internalizing symptoms: they’ve been bullied, and now they’re feeling socially anxious or depressed. A lot of times, people [then] turn to substances to cope with those feelings, because it can numb those feelings in the moment. But of course, it contributes to this vicious cycle of feeling bad and using more substances.”

Communities at large tend to disregard the complexities of substance misuse, which creates a misinformed perception around the issue. Not only is information surrounding addiction limited, but certain hurtful parlance can lead to further stigmas that include victim blaming and a degrading of those who are struggling. This is why terminology is evolving into a more accurate, progressive way of addressing the one grappling with addiction.

“The health and addiction field is moving to use different terminology surrounding substances,” Kataria states. “So, instead of saying substance abuse, which stigmatizes drug use and treatment, by using the word ‘abuse,’ which has a negative connotation attached to the user, we are shifting to use alternatives like substance misuse, or substance use, or dependence or addiction,” This shift in language also hopes to regulate the issues in dealing with drug misuse and addiction without degrading the user.

Eliminating the stigma that surrounds drug misuse and addiction is by no means an easy task. Perceptions and the damage those perceptions can have are not so easily erased, but through education, meaningful discussions, open mindedness, other individual and community efforts, stigma can be dissolved. Whether they realize it or not, parents, guardians and other family members can have a great impact on how a teen views and interacts with drugs. Whether family members have open conversations about drugs, and if teens believe they will be punished, can influence whether use, intervention or support will be sought out. If a teen feels that their guardian may have a strong, visceral reaction to topics regarding drugs, they may be afraid to bring up the subject or seek help and the problem may be magnified.

“I think for a lot of parents, realizing that needing external help is important and it’s not something that you can just fix at home can also be super important,” explains Kataria. “I think something that I once heard in a webinar was the L.O.V.E acronym, and that’s what we often tell parents to use is the ‘Listen Offer Validate Empathize’ acronym, which I feel like applies to everybody. But parents, especially where they actually listen nonjudgmentally and offer—not offer advice or scare tactics—but offer their opinion, validate what the teen is saying or sharing with them and empathize with their experience instead of judging them or going against them without really understanding how they’re feeling.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Nashville in November 2025, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.