Technological troubles in teaching: how mobile devices affect education, ETHS

Phones helped students stay connected during the pandemic. Now, teachers grapple with how to get students to connect in real life.

Over the past 15 years, they’ve sparked controversy in classrooms, made board meetings into battlegrounds, and permanently altered long-standing policies in schools worldwide. The pandemic only increased their hold on students, leading to more intense crackdowns than ever. What could possibly influence the education system in such a way? The answer is simple: cell phones. According to Common Sense Media, teen screen use increased 17 percent over the past two years. Now that in-person school is back in session, teachers and administrators are struggling more than ever to keep students off their phones in the classroom.

“Phone addiction exists. It’s a lot, because teachers are in the trenches with the students every day, to continually reinforce that [idea of] let’s just be together and be present as a community,” English teacher Liz Shulman explains.

Many ETHS teachers share this feeling, and concede that phones in the classroom are a notoriously difficult issue to tackle.

“Last year, I tried to remind my kids to be mindful, to be present, to be in class, stay engaged [and] don’t rush the work, maybe go back to the work if it seemed like it was rushed through. It seemed like [with] the phones, [it] was like, ‘Oh, as soon as I’m done, I can be on my phone,’ which I think harms the depth of writing, research and thinking that students can actually do. It never hurts to just sit and think awhile sometimes,” says Sara Young, another English teacher.

The years following the pandemic saw a large uptick in students’ addiction to technology, specifically cell phones. Technology had been one of the only things that allowed people to connect with each other even when everyone was stuck at home, and many teachers have noticed the increase in technological use that students endured remotely has translated into the classroom setting.

“I think the teenage brain is wired for being social, and [phones are] really the mechanism that students use to be social and to connect with one another. We all really crave connection, and the way to connect, especially during the pandemic, was through technology,” Technology Integration Specialist Mina Marien explains. “Just like anything else, making connections is a skill, and you get good at whatever skill you practice. Students have really practiced using phones to connect with one another on social media, just by text [or] playing different games, and so I think that is really what students want to do. They want to feel connected and involved with their peers, and [they] don’t want to feel like [they’re] missing out. If everything’s going on online, then you want to be part of that action, even if you’re not fully participating in it, you want to be on board, so I think that’s why a lot of people like phones, and [this is] especially prevalent for teenagers, because that’s the phase of brain development that students are in at that time.”

In addition to acting as a vehicle for social interaction, phones can also be a tool for students to turn to when they experience anxious thoughts, which was another aspect of phone usage that was amplified by the pandemic.

“A lot of studies show that students relieve anxiety by having coping mechanisms and sometimes that is using the phone. Obviously the pandemic was pretty anxiety causing, so having the phone as an attachment is sometimes a way that students tried to [cope with that anxiety],” Marien continues. “The problem is that [phones are] not helping the kids learn. As much as I accept that there are good uses for the phone that helps students, I think that we need to go back to trying to find other ways to help relieve anxiety that’s not just being tied to the screen. I do think [student phone usage has] gotten worse [since the pandemic], but I hope that we can continue to try to find more productive strategies for helping students engage and be comfortable at school.”

The primary way in which ETHS is attempting to combat phone usage is a new phone policy. The ETHS Pilot states that phones need to be out of sight and not used during class time. Violation of these guidelines can result in a call home or a dean referral and allows for an ETHS staff member to potentially search through a student’s phone. The policy also prohibits the use of earbuds and other electronic devices. This is vastly different from last year, when students frequently used their phones during class, even if the teacher was explaining something important. In light of this stark transition to a new policy, ETHS staff and students have expressed mixed opinions regarding its purpose and efficacy, many of which are positive.

“We’re here to learn, so I guess it is good that we focus on learning and put the phones away,” says Chris Fargo, an ETHS sophomore. “I think it actually helps me because I stay more focused. I don’t know about some people, they’re not that distracted by their phones, but for me, I get distracted pretty easily by my phone, so it’s really helpful for me.”

Many teachers have reinforced this viewpoint that the phone policy helps to eliminate distractions in the classroom, yet some teachers still think there is more work to be done.

“I think it’s a great start. We have all the data and the research that shows that students are distracted on the phone,” says Shulman.

Some teachers, like Sujud Ottman, a biology and urban agriculture teacher, have implemented creative strategies to thwart phone use.

“If I have to tell [a student] a second time during class period to put their phone away, I just give them this envelope, and it explains my phone policy, and what they have to do is take their phone, they put it in the envelope. The envelope stays with them, but they’re not allowed to take it out until the end of the class period, and not even on breaks,” she explains.

Active enforcement of the phone policy hasn’t been noticeable or a positive change for all students though.

“It just doesn’t really seem to be doing anything in terms of [stopping] kids [from] actually using their phones, and even if it is enforced, it doesn’t seem to be doing anything. I don’t really see it [working], it just seems to be adding more stress to students and teachers,” says senior Sachin Clark.

While the new phone policy seeks to help students focus and maximize their learning, for some students, it may be more distracting than helpful. The long classes of the block schedule have students focused for longer periods of time than with previous schedules, which can make phones especially appealing.

“I think the new phone policy, in addition to the block period, is not great, because it’s already really hard to focus for that long and retain so much information, and I like to use my phone to take breaks sometimes in class,” says Clark. “I don’t think that being on your phone in class is great, because it’s distracting you from learning. At the same time, it’s also an hour and a half of learning, so most of my classes offer breaks during that time.”

Having students learn to self-manage their phone usage is also a concern. As students graduate high school, they will have more independence and will have to be more responsible for their own time.

“I don’t actually think phone policies help. It’s teaching the opposite of self reliance. It has you depend on other people to decide when you should be paying attention. If we’re trying to prepare for college, we need to learn to do that for ourselves,” says Kathryn Zehr, an ETHS sophomore.

One of the other popular counterarguments to the phone policy pertains to students with disabilities or mental disorders. It’s often said that cell phones help these students stay focused in class and work more efficiently. According to the Council for Learning Disabilities , “A mobile device can be considered as assistive technology (AT) for some students with disabilities … Due to its ubiquitous use among middle and high school students, students with disabilities are more likely to use a mobile device and feel less stigmatized than if they were carrying an AT device.”

Technology use in the classroom could help many students who may often feel overstimulated or ostracized in school environments, yet the phone policy holds no exceptions for students with an Individualized Learning Plan (IEP) or 504 Plan.

Despite the benefits to an individualized method of considering different students’ needs when it comes to phone usage, many ETHS staff members view a consistent and unified phone policy to hold important benefits as well.

“It’s becoming a school-wide culture shift with the phones…because when it is left up to the teachers, there’s just so many varying philosophies and ideas,” Melanie Marzen, another Technology Integration Specialist, explains. “[Phones] really get in the way, from a teaching standpoint, of social-emotional development in the classroom, classroom connection and being able to do what you need to do to make the class work efficiently and appropriately. If teachers are doing different things in the classroom [in regards to phones], then it kind of pins one teacher against another.”

Nonetheless, this inconsistency regarding phone policy enforcement still persists across classrooms.

“Some teachers are more lenient, some teachers are really strict about it,” Fargo shares, in reference to fulfilling the phone policy.

This lack of cohesion can not only be frustrating for students, but it also creates a wavering communication line between students and their guardians. Phones are the primary source of contact between parents and students during the school day, and eliminating that direct messaging system can have significant consequences. After the lockdown last year, many students feel a sense of security with their phones as both a source of information to follow current events and a service to immediately connect with others.

“See, my wellness teacher keeps saying the phones should be kept outside of the classroom. I think that’s ridiculous. Phones shouldn’t disturb class, but they should be kept on, they should be able to be kept on your person,” Zehr explains.

Nevertheless, many parents have praised the new phone policy with the hope that it will minimize phone addiction among their children.

“I just wish kids would realize how much their phone is taking away from their actual potential to be in the present moment,” ETHS parent Annie Lesch states, “Or how much happier they are when they have had a break from their phone and how they actually feel after not being on their phone. I feel like it is a maturity thing.”

While there are many different angles to consider while analyzing the phone policy and its usefulness, it’s important to keep in mind the fact that the ETHS community is still reeling in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the lasting effects could take years to shake.

“It’s really hard to talk about [phones] without talking about remote learning and the pandemic. All of us were on the phones all the time when we were on Zoom or Google Meets, adults as well,” shares Shulman.

Role of Technology

Aside from solely mobile phones, technology as a whole has assumed a significant position in schools across the nation, which has stemmed benefits and drawbacks regarding the educational impact.

“I think technology can take on a lot of roles within that [educational] space. I think one of them is providing students with additional ways to express themselves and to explore ideas, [and it] can also be [used in] additional ways for teachers to be able to engage with their students,” explains Dr. Marcelo Worsley, an assistant professor of both computer science and education and social policy at Northwestern.

Worsley expands on the way in which technology’s progression allows for teachers to approach their curriculum in more creative, individualized methods.

“I think technology can also be a way to give teachers more direct access to creating the types of learning artifacts and types of learning experiences that they want there, that they want their learners to engage with.”

Despite the seemingly limitless powers of technology, teachers still question whether technology’s current application in education is appropriate.

“I think [this] generation is going to have a lot to reckon with, because I think [this] generation, more than any other, is digitally dependent, and what are the implications of that?” Shulman asks. “If teachers are working very hard to create the lessons that we push out through Google, [because] Google has infiltrated every classroom in America, technically, do they own the creative work and lesson planning that teachers do, because it’s all through Google?”

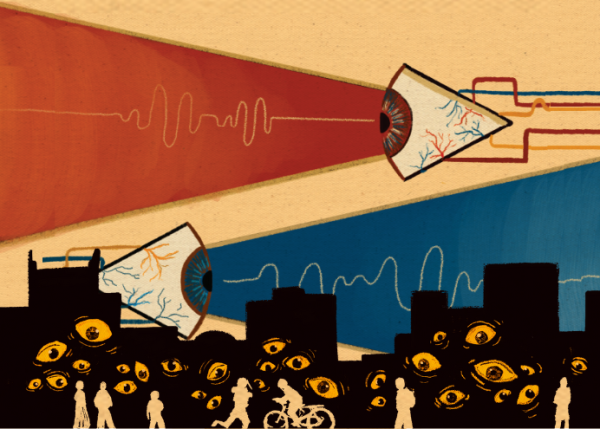

Shulman raises important questions that indicate the degree at which technology micromanages the educational system. School software systems contain a pool of personal data, which makes schools particularly vulnerable to security threats. Data breaches can result in the release of sensitive and confidential information regarding students, staff members and parents, or as Shulman articulates, data archives could grant companies overwhelming control over the creative and intellectual property of teachers and students.

“Having any kind of technology that is recording anything about students and teachers in the classroom can be highly problematic if not done in ways that are ethical and really provide students with direct access to their data and make sure that the models that are used are transparent and not overly biased,” Worsley explains.

Following security concerns, technology’s ubiquity across learning environments can also serve as an obstacle to student focus and interest.

“There’s ways that students have to be accustomed to being able to have access to that kind of technology” Worsley notes. “When I was in school, we had Texas Instrument graphing calculators, [and if] you walked into any class, you’d see a handful of students playing Tetris or one of the other games. Those same kinds of things can happen within the existing context of people being on their computers or being on their phones, and ultimately getting distracted from the learning experience.”

Essentially, technology possesses a paradoxical nature within an educational setting: tools that are intended to promote learning can also be the largest distractions in achieving this goal. The pandemic highlighted this theme as schools across the country struggled to establish a school year that functioned primarily off of technology.

“[Technology] has completely changed education, and I don’t think that we can effectively talk about it without talking about the pandemic, because [through technology] was the only way that we could connect with our students. I’m so grateful that we were able to, but it was done in very isolating ways,” Shulman shares.

However, Shulman continues to explain how the pandemic’s learning system, while unideal, was able to bring to light new ways of considering technology as an instrument to cater to different learning styles.

“I still have some students who miss it. I have students who wouldn’t necessarily speak when we were on Zoom, but they would put a lot in the chat or [participate] all the time when we were in small groups in the breakout rooms. I put students into 25 different breakout rooms, so that I could conference with each one of them, and I was like a frog jumping from one room to the next, and you don’t have that in [the physical classroom],” she elaborates. “It definitely was a different way of communicating, so I think it brings up the question of how do we integrate that? We can’t go back, we have to figure out how to go forward.”

In the spirit of moving forward, many have recognized that the pandemic has permanently shifted the way in which technology is used and perceived, and the biggest change is the amount of time spent using technology. According to a study conducted by the Pew Research Center, 40 percent of U.S. adults reported using digital technology in ways that they hadn’t explored before the pandemic. Schools are no exception to this pattern, through digital platforms, including Zoom, Google Drive and Classroom, Flipgrid, Padlet and more, teachers and students have learned various new ways of connecting digitally.

“I think there are aspects of [the pandemic], where people now see that we don’t actually have to do everything in person. We can do things more remotely, we can find ways to give students more autonomy over their own learning by having them do more asynchronous activities,” Worsley explains.

However, this dependence on digital resources for curriculum elicits inequity and exposes disparities regarding access to technology.

“[During the pandemic], we also saw the ways that those opportunities were inequitable. You had some students who were able to really take advantage of [their technological resources], and they grew a lot academically during the pandemic, and others who didn’t have access to the same types of resources [didn’t learn as much].” Worsley notes. “People were socialized differently during the pandemic, and they’ve been socialized into a different way of thinking about [and] engaging with learning . . . I do think people are starting to really consider the ways that we used technology during the pandemic [and] which aspects of that we want to maintain [and] which aspects we want to forget about.”

Dr. Worsley highlights a long-standing struggle within the education system of the exclusionary effects that technology presents. In an attempt to provide students with the same access to digital learning tools, ETHS, following a national 2010s trend, administered a Google Chromebook to every student in 2016—a policy that has continued for every year since.

“When I was teaching, we didn’t have Chromebooks,” Marien begins. “Everything is different [now], because the computer is completely essential to all learning at ETHS. It really has transformed how we do school and the things that are possible. I think it has been powerful in personalizing learning, and really letting students explore more diverse passions and perspectives than we could have when it was just the teacher teaching. Now, we have the teacher and the entire internet at our fingertips, and with thoughtful instruction and planning, I think teachers really harnessed the power of the internet to make learning deeper for kids and more personalized.”

Despite this learning shift, ETHS is still one of many schools nationally that faces concerns regarding technology and inclusion.

“Anytime someone does a PowerPoint presentation or does a slideshow, and you have a student in the class who may be blind or low vision, and they don’t have direct access to that document, [for example], maybe people have not included alt text for the images or even as they’re giving a presentation, they’re not describing what is on those slides, [then] you’re already making for a less inclusive experience. A lot of the web content that’s out there is not designed for people with disabilities in mind,” Worsley shares. “Perhaps you have a fine motor impairment, [and you’re] not able to type as well, but if you’re able to use a speech based interface to help [you] as [you’re] trying to write a paper, [you can be more successful]. Even beyond that, and this is something I do in most of my classes, [is] allowing people to submit their assignments in other forms. It doesn’t have to be a two page to three page document, they can submit a recording of a conversation, they can submit a drawing, they can submit a comic, [so] that there can be a variety of ways that people can demonstrate their knowledge, even within the sort of traditional classroom setting.”

Significantly, the improvement of technology is an effective solution to diminishing some of the inequities that digital learning has revealed. As technology continues to progress, schools are constantly considering the most beneficial ways to implement these tools into their classrooms, because regardless of contradicting opinions surrounding technology’s place in education, one thing is for certain: technology is here to stay, and its presence will only continue to enhance.

“There’s something called the SAMR model, which is substitute, augmentation, modification and redefinition, and those are the levels of how learning can be changed through technology,” Marien clarifies. “I don’t know that every single use I see for technology is in the redefinition phase, but more and more, I’m seeing teachers redefine what learning looks like with their technology. It’s personalizing [education, and] it’s really building in choice and skills that kids are going to need after ETHS. All that is happening, so I do think we’re definitely seeing a lot of redefinition of what learning looks like.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Nashville in November 2025, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.