Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

Just a 30-minute cab ride away: An inside look at North Cook Young Adult Academy

Students found eligible for expulsion following Pilot violation can opt for alternative school education.

December 16, 2022

Jian Kramer couldn’t remember how that pocket knife even got there in the first place.

Could he have found it somewhere and decided to toss it in his backpack? Had someone used his bag and left it in there by mistake? Perhaps he needed it for some project and forgot about it all together.

But, now, it sat in the palm of the safety officer’s hand, staring Kramer back in the face: a mindless error that would change the course of his entire high school education. He didn’t expect anything to come of it when the safety officer began searching his bag. He knew he was already in trouble for the vape cartridge that had prompted the search, but he also thought he was a non-threatening kid; he didn’t have anything else to hide.

When the safety officer pulled out the pocket knife, Kramer was promptly given a choice between two options, the first being to appeal to the school board and potentially face expulsion.

“[The administrator] was making it very clear that I had no chance of succeeding [with an appeal], and I would be kicked out,” Kramer recalls. “[The administrator said if I did appeal], I’d probably have to take a year down due to disciplinary reasons, I’d have to find another school and there’d be a huge gap in my transcript. But [the administrator] kept it very light, assuming that [my parents and I] would go with the other option.”

The ‘other’ option was to pursue an alternative education at North Cook Young Adult Academy (NCYAA), and that’s what Kramer chose to do, with no idea of what lay in store. At 7:00 a.m. every weekday, he’d watch a taxi turn the corner onto his street, always hoping it would just blow past his home and always met with disappointment as the car rolled to a stop out front, waiting for his arrival. He’d saunter down his steps and find himself slouched in the backseat of the school-ordered cab for upwards of thirty minutes until he would be dropped off at his school for the day. Upon arrival, Kramer would join the line of his fellow classmates to enter the building.

“They would bring us in one or two at a time with metal detectors, and the principal and the vice principal would be there with metal detectors,” Kramer’s peer Luke Jackson*, who attended NCYAA around the same time, recalls. “We’d take off our shoes, they’d first scan our shoes, and then we’d put those to the side. Then they’d scan our bodies, and then we’d have to go like this”—Jackson lifts his foot off the ground and points towards the sole of his foot, which was pointing toward the sky—“and they’d scan the bottom of our socks.”

The students then habitually held out their phones and jackets so the faculty could confiscate them and lock them up until the end of the day. Backpacks were prohibited unless they were transparent.

As he reflects on his time there, Kramer takes a deep breath before collecting his thoughts. “We weren’t treated as people; we were treated as threats,” he says. “We had to do what they said, or they got rid of us.”

The Origin

In 1995, Illinois Public Act 89-383, also referred to as the Safe Schools Law, established the Regional Safe School Program (RSSP), declaring that “Disruptive students typically derive little benefit from traditional school programs and may benefit substantially by being transferred from their current school into an alternative public school program.”

Today, there are about 80 locations across Illinois that offer curricula under the RSSP, NCYAA being one of them. According to the law, these sites must be located “far away from any other school buildings or school grounds.” The act was passed, in part, to provide aid to students who are unproductive in a traditional classroom model. The second component was to manage classroom disruptions and maintain safe learning environments by removing students who pose threats to a constructive educational experience—the latter being a particularly important issue to parents and guardians in the minds of the lawmakers at the time.

“Parents of school children statewide have expressed their rising anger and concern at the failure of their local public schools to provide a safe and appropriate educational environment for their children and to deal appropriately with disruptive students, and the General Assembly deems their concerns to be understandable and justified,” the law continues.

However, this statewide attempt to enhance the classroom atmosphere for most students is often at the expense of “disruptive” students, as the law refers to them, and their education.

The Offense

In order to begin to understand the operations of these alternative learning programs, it is essential to recognize what qualifies a student as “disruptive.” According to the NCYAA website, RSSP works with students who are either at risk of expulsion or have received multiple suspensions at their respective schools.

There are a multitude of offenses that could warrant a suspension, or even an expulsion, at ETHS. However, recently, there’s been an increased focus on violations related to weapons and student safety.

“I think the event on December 16”—the lockdown that occurred last school year after two loaded guns were found in the school—“gave us an opportunity to be reflective of our practices and policies and how we respond to them,” explains Associate Principal for Educational Services Keith Robinson. In addition to reexamining physical components of the building, such as fences, bushes and entryways, ETHS has also tried to limit the amount of weapons that are brought to school—both efforts with the goal of monitoring safety. “We really began to promote and market what students should not bring,” Robinson continues.

The ETHS Pilot states that the possession of any weapons on school property, including “firearms, ammunition, knives of any kind, tasers … mace, dog spray and pepper spray” may warrant up to two years of expulsion.

The Process

If found in violation of ETHS policy, a trip to the dean’s office is the first step. Then, the dean outlines the given consequence for the offense. If a student is dissatisfied with their consequence, they may choose to appeal to Robinson, where they may either be given a less severe consequence or receive the same penalty as before. A student may continue to appeal after this, next speaking with Assistant Superintendent and Principal Taya Kinzie, then Superintendent Marcus Campbell if they appeal once again. The final decision to appeal comes in the form of a school board hearing. Meaning, any of these stops along the way have the jurisdiction to terminate the possibility of expulsion, with Campbell having the ultimate authority over whether or not a student is presented in front of the board for expulsion. If he does not believe a student should be expelled, he maintains the right to not bring them before the board. If the student does find themselves appealing to the board, the decision is ultimately out of the control of ETHS faculty all together. Any student who faces the possibility of expulsion must undergo a board hearing, and the board is the sole authority over whether or not the student will be expelled. This leaves many students facing the same choice: either risk their chances with the board or enroll at NCYAA.

Earlier this year, Mayra Bazan Gonzalez, a female senior, went through several different stages of this process when she was found with pepper spray at an ETHS home football game during a bag search prior to entrance. At first, she was given a 10-day suspension and a recommendation for expulsion. After appealing the first time, she was given the option to attend NCYAA as an alternative route.

“When I looked [NCYAA] up, it was very scary to think that I could be going there, because I didn’t think that I aligned with what their mission statement was, which was serving students who had multiple suspensions or [an impending] expulsion. I didn’t see myself as that type of student or person, so to have that be the repercussion of my actions was very terrifying,” Bazan Gonzalez recalls.

Fortunately for Bazan Gonzalez, she received strong support from her peers and the surrounding Evanston community throughout this process. Soon after the initial incident, a petition,** titled “End Mayra’s Suspension & Potential Expulsion from ETHS,” was created and read “She brought pepper spray because she had to walk home that night, and wanted to protect herself. Now, Mayra will most likely be suspended for 10 days, put on social probation and recommended for expulsion.” Underneath, bolded words read, “Mayra is a woman of color. She also has no criminal record and is an active community member and student.”

The petition garnered over 2,700 signatures, and after a third appeal, Bazan Gonzalez was ultimately penalized with a three day out-of-school suspension, four day in-school suspension and three days to work on a restorative project with her dean. She was also placed on social probation until the end of the first semester, but she would still be able to attend her extra-curricular activities. Although Bazan Gonzalez was ultimately able to continue to attend ETHS, many students in similar situations do not have the same social resources to back their cases.

When Ashley Williams* came to school last year with pepper spray, she had no idea she was even breaking school policy. ETHS policy equates pepper spray and firearms despite the fact that, according to the Vision Eye Institute, pepper spray does not cause any permanent damage to vision or the eye.

“As a girl, I feel like you should be able to carry mace around, especially, because I was working at the time, so I walk home from work. I get off at nine or 10 [p.m.], so I feel like I should be able to bring that for my protection and for my safety,” she expresses.

Williams shares that she was first sent to the dean’s office because another girl she was with at the time had “smelled like weed.” Once she arrived at the dean’s office, the dean explained they had to conduct a search. When the dean asked Williams if she had any weapons on her, Williams explained that she carried pepper spray on her keychain.

“I never knew that you couldn’t have mace [at school], because I really would never have had anything [like that if I’d known], but I never knew you couldn’t have mace,” Williams emphasizes.

Williams was provided with the same choice as Kramer—either try to present an appeal against expulsion, which the administrator stressed was likely to be unsuccessful, or attend NCYAA for the rest of the semester.

“Expulsion by law means that you can’t go to ETHS, and you can’t go to any school in the state of Illinois, for a year, and sometimes it’s two years you can’t go. Our board’s and my philosophy is, ‘Who would want to keep a kid out of school for a whole year? Or two years? If so, it would need to be pretty egregious,” Campbell says.

Williams did not want to risk her chances with the appeal. So, her punishment was to spend the rest of the year at NCYAA on top of social probation, meaning she could not attend any ETHS events, including dances and home games. Despite her choice in the matter, she still felt dissatisfied with the result.

“I noticed that everybody doesn’t get disciplined the same. I wasn’t a bad student; I never got suspended at ETHS. That was my first time ever being expelled or suspended or anything my whole high school life,” she shares.

Williams, a Black-identifying student, is not the first to point out the disproportionate disciplinary action within ETHS and across national school institutions.

The Disparity

Altogether, since 2013, Black and Hispanic students have experienced close to six times as many in-school suspensions than white students, and eight times more out-of-school suspensions, according to data compiled by the Illinois State Board of Education. In the 2021-2022 school year alone, 77 in-school suspensions were given to Black students, compared to only 32 for white students. As for out-of-school suspensions, Black students experienced 59 suspensions, compared to only 13 suspensions for white students. These numbers aren’t proportional with the overall demographics of the school, as 45.6 percent of ETHS is white but white students accounted for only 15.2 percent of total exclusionary incidents in 2021.

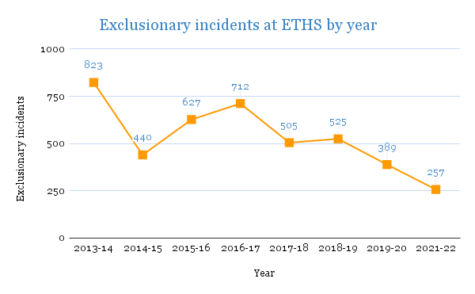

On Sept. 15, 2016, the Illinois State Senate passed Senate Bill (SB) 100, which prohibited zero-tolerance policies of suspensions and expulsions. Under SB 100, out-of-school suspensions and expulsions can only be used if a student’s continued presence poses a threat to the student body. The effects of the bill are visible when comparing data from 2013-2014 to the most recent data. During the 2013-2014 school year, there were 598 incidents of in-school suspension at ETHS and 225 cases of out-of-school suspension. Most recently, in 2021-2022, those numbers dropped to 169 in-school suspensions and 87 out-of-school suspensions.

Although suspensions overall dropped, the racial discrepancy has remained a constant problem. During the 2013-2014 school year, 93.26 percent of all suspensions were given to students of color. During 2021-2022, that percentage decreased to 84.4 percent. This is an improvement, but the fact remains that even after SB 100, students of color are disproportionately affected by ETHS’ suspension policy.

Evanston is far from alone in this trend; school districts nationally have unequally scrutinized and punished their students of color, and administrators are still grappling with how to extinguish this trend.

“Yes, no one is satisfied with [disproportionate outcomes] in discipline. That’s why we continue to do proactive interventions, including restorative practices,” Robinson shares. “Over the last five years, we’ve seen a downward trend, though we are not satisfied, and understand that there is a lot more work to do.” shares Robinson.

When considering the disciplinary rates for neighboring schools, the ISBE suspension and expulsion data makes clear that this discrepancy is an ongoing issue. At Maine East, Maine South, Maine West, Niles North and Niles West, a higher percentage of suspensions and expulsions are accounted for by students of color than the percentage of students of color in attendance of the school. For example, 4.91 percent of students are Black at Maine East, yet in the 2021-2022 school year alone, Black students made up approximately 23.86 percent of total incidents for in-school suspensions, out-of-school suspensions and expulsions. That same year at Niles North, Black students accounted for 54.84 percent of total incidents despite Black students making up 9.02 percent of the total student population and at Maine West, 44.87 percent of students are Hispanic or Latinx, but Hispanic and Latinx students made up 65 percent of all incidents. Despite intentional efforts across Illinois to close this gap, the statistics still evidently show disciplinary differences between white students and students of color for many of the schools the In-Depth team looked at for this article.

Two of the key factors that lead to the continued marginalization and punishment of students of color more than their white counterparts are profiling and implicit bias. For senior Amira Grace, there was a day when a safety officer approached her and told her she had to go to the dean’s office.

“The safety officer never disclosed to me what I was doing wrong. [They] just led me to the dean’s office and said it [was] time for [me] to be searched. They did not tell me what I was in trouble for. They separated me from my friend, and I was searched first. They went through every little part in my bag and didn’t find anything, because I didn’t have anything,” says Grace, who is a mixed, light-skinned Black girl.

“Considering what I know about implicit bias, I definitely think that it was racially charged, especially considering [that the security officer] was white; also considering times when I’ve seen groups of white girls in bathrooms doing what they please, talking really loud, maybe doing stuff that isn’t allowed and nothing happens at all, when me and my friend were just talking.”

Grace’s experience is just one of many that illustrates a larger trend of profiling within ETHS’ disciplinary system.

“Most of the people that I talk to about getting searched by safety are students of color,” Grace says. “When I do talk about my experiences and other students of color’s experiences, white people that I tell [always say] ‘What? I did that exact same thing and nothing happened!’”

Profiling remains a complicated issue for a myriad of reasons, one of which being the internal, and often subconscious, factors that influence which students are being targeted.

“It’s hard to address that kind of implicit and explicit bias [within faculty], because it’s so individual, and it’s so everyday, and it’s so normal. How do you get a person to think about, ‘Who am I watching and why?’ Some people aren’t even aware of it,” Campbell says.

Another contributing element that perpetuates the cycle of profiling is the lack of reporting around these incidents.

“I haven’t had students directly report [being profiled]. That doesn’t mean that students aren’t experiencing [profiling]. If they are, I’d like to know. We’d love to talk with them, understand their experiences [and] think about how else we need to structure and provide that support,” Kinzie says.

However, the reporting process can be more emotionally taxing than it might seem, which can explain why many students may choose not to file a report with the administration about the profiling they encounter.

“In my experience, talking with administrators, even those [who have a reputation for being] more empathetic, I still feel attacked,” Grace shares. “There’s definitely charged language, but that’s always how I feel. There’s always this power dynamic that’s so extreme between the two of us, which leaves room for them to belittle your intelligence without consequence.”

All of these biased disciplinary tactics bleed over into the demographics that appear at NCYAA, an institution that serves as a disciplinary consequence for students. NCYAA partners with an assortment of schools in Northern Cook County, including, “Niles, Rolling Meadows, Buffalo Grove, Des Plaines/Maine Township and Glenbrook,” according to Lisa Fornwald, the director of NCYAA. Demographically, Cook County is approximately 26 percent Latinx and 23.7 percent Black, and Fornwald shares that NCYAA is comprised of mostly male students who identify as either Hispanic or Black.

The Experience

Upon discovering their impending enrollment at NCYAA, many students feel a sense of shock knowing that they will no longer attend ETHS. However, the difference between going to school at ETHS and NCYAA is a lot more than just a different location and name.

Once in the school, several students recalled a police presence, especially when a conflict arose within the school, which contributed to the feeling of being treated as a “threat.”

“It creates a state of fear. I mean, you’re living in anxiety like, ‘Oh, I gotta stay in line’ … You [have] to worry about all the rules, because you’re afraid of the consequences constantly,” Kramer shares.

It wasn’t just the atmosphere and sense of freedom that was different. The curriculum and academic resources available at NCYAA also varied greatly from those at ETHS.

“It was a lot different going into that kind of learning environment as opposed to ETHS,” senior Krish Anderson*, who was sent to NCYAA after vandalizing school property, explains.

One large difference between NCYAA and ETHS is that the former is an incredibly small school, with only a few classrooms and around 10 kids in each class. In fact, many of the classes are conducted online, with minimal homework.

“[The curriculum] was just what you needed to do for credit completion,” Anderson says of his classes.

At NCYAA, the curriculum is designed specifically for credit recovery and improving overall student behavior. With NCYAA’s smaller size and more specific academic focus, not all academics will be necessarily similar to those a student was previously taking at their original school.

“We don’t have all of the academics that the public school does, so we try to give comparable assignments or comparable classes. If a student is taking…culinary at Evanston, well, that’s something we don’t have. We will have to give them a different [class] while they’re here, but for all of their basic core classes … we offer comparable classes,” says Fornwald.

This more basic curriculum proves to be helpful for some, but fruitless for others.

“It was like going back to an eighth grade science class,” Jackson describes.

With simplified classes paired with the sense of constant surveillance, the entire learning experience is worsened for many students.

“Looking back, it felt demoralizing because of the level of academics. I felt like I wasn’t really working towards my future. I would say there was a melancholy mood in school. It felt like all the kids just wanted to get out of there, and it felt like the teachers didn’t really care,” Jackson recalls. “It was just very cramped, very small; you didn’t really get to see the outside … It was a lot like prison.”

This different experience in contrast to what most ETHS students are used to in regards to their schooling can have significant mental impacts.

“My mental health got pretty bad during that time. Some of it was outside factors, but I think just being in that very boring, nothing happening, ‘do what we say’ kind of environment, it takes a lot out of you,” Kramer expresses. “I remember, near the end of the year, I was just like a soulless drone, kind of just going through the day…. I don’t know if I’d say it was traumatic, but it definitely has lasting impacts on me.”

Beyond academic frustration, the school can also be very socially isolating for students who try to stay attached to the ongoings at ETHS. Students who are sent to the RSSP at NCYAA from ETHS are not allowed to attend any school social events, and they’re only allowed a limited amount of contact to ETHS per week.

“I never experienced something like this, being away from my friends,” shared Williams, whose main obstacle was struggling to make friends at NCYAA.

The Return

Upon returning to ETHS at the beginning of this school year, these students were, again, faced with a completely new routine than that which they had been accustomed.

“[You’re coming from an environment] where everything was just handed to you. You didn’t have to think much, you just had to do, but now you have to learn how to be your own person again, day to day,” Kramer says.

In addition to the internal readjustment that must occur when returning to ETHS, there is also a lasting effect on the external reputation that can be hard to shake. Not only can attending NCYAA affect your future going forward, with the school earning a spot on one’s permanent record, but the social effects can persist as well.

“For these kids coming back to their school, they’re kind of like an outcast,” Jackson describes.

“I get treated different sometimes, and I’ll see my friends from alternative school, the people that I was interacting with a lot, and they’re usually sticking together, not with their own previous [friend] groups,” Kramer shares. “There is a reputation that comes with an alternative school.”

Despite the various challenges that students face throughout all steps of this discipline process—whether that be before, during or after attending NCYAA—the RSSP can still hold value for some students, including a return to ETHS with a more focused lens on their academics and behavior.

“I couldn’t fathom how important school was until they put me in a situation where I couldn’t take advantage of it,” Jackson explains.

For this reason, NCYAA is deemed effective when considering reintegration; after experiencing NCYAA as a consequence, proponents would argue students will be less likely to repeat such actions that landed them there in the first place.

“For the most part, if you’re looking at the recidivism rate for students who make egregious errors, there is a significant reduction because of the targeted supports offered,” Robinson shares. “All behaviors are typically a symptom of something else. Those may include academic and socio-emotional challenges. In the case where students express a need for more intervention, there are some opportunities for students to receive credit recovery, more mental health support and to have more fluidity and connection in their school.”

Deciding to send a student to NCYAA is not an easy choice to make, but for administrators, it can be the best choice. School systems across America have felt the pressure to keep their schools physically safe, but these increased safety measures can come at the cost of students’ emotional wellbeing. Meeting all of the educational, social and safety needs of students can be a difficult juggling act, and administrators are still grappling with the best way to approach this task.

“Having good relationships with students [helps] them be seen or understood, [so that] they don’t want to act out if they’re having conflicts,” says Campbell. “Those are the things that keep schools safe; it’s relationships.”

The inherently difficult aspect of forming relationships between students and faculty at a school like ETHS, is the size. With over 3,600 students, the discipline process can sometimes appear to lack empathy and a sense of humanity.

“Once [the administrator] processed me, [they] moved on. It felt very impersonal, I just felt like another ticket, you know? Another form to fill out,” Kramer explains.

Due to the size of ETHS, precautions that are taken to make school a physically safe space can be at the expense of the mental safety for some students, and students, like Kramer, are calling for more conscientiousness when it comes to discipline.

“I was also going through a lot before I got kicked out of school, and my actions were a result of how I was feeling, and the actions [I experienced] in that school made that worse,” Kramer explains. “If [the faculty] would’ve taken into account students’ lives, like mine for example, I probably wouldn’t have gone through as much.”

Editors’ Notes:

The Evanstonian doesn’t condone any violations of the Pilot.

*We have changed the names of certain students and identifiable details in order to protect their privacy.

**The Evanstonian wants to acknowledge a conflict of interest when it comes to reporting this story, as Executive Editor Meg Houseworth created the petition mentioned in the article.