Cycles of shame: How culture, family, social media influence dietary mindsets

February 7, 2023

Family Influence

Food: for many, it’s a typical part of everyday life. For others, however, it is so much more than that; food can represent culture, inspire people and connect families.

Unfortunately, despite all of this, society has stigmatized the simple act of eating food. Generational cycles, social media and pressure from others have caused many, like ETHS student Lucy Littenberg*, to struggle with eating. Littenberg recalls sitting at meals, surrounded by extended family, listening to them complain about their weights. She absorbed the comments they made, the diet regimens they bragged about and the warped standards they strove to uphold. Those words began to replay in her head whenever she looked in the mirror; questions about her own body began to burden her endlessly.

“In some of my extended family, other girls were very conscious about their weight…since they were obsessed with their [eating habits], I became obsessed with mine,” she says.

Eating disorders, by nature, are competitive. Details of disordered eating frequently fuel and worsen someone else’s relationship to food, and as a result, an unhealthy perception of eating and body image plagues multiple generations. According to CNN, 61 percent of adolescents have experienced “body dissatisfaction,” and one factor is often overlooked: family. Even in environments where family members only comment on their own weight, their statements can perpetuate societal standards and create a dangerous awareness of calories and food.

“I know people whose mothers are constantly body checking or don’t get buns with their burgers because they’re afraid of the carbs or just [engage in] negative self-talk,” ETHS student Stella Scott* explains.

Oftentimes, people try to avoid certain foods to lose weight. While this can be a beneficial practice if done safely and with the correct information, many foods have become stigmatized due to their portrayal in media and within families. Relatives making offhand comments such as “this is too many calories,” or “I’m going to need to work off these carbs” plant detrimental seeds in others’ brains. Suddenly, it might seem like too much to have another roll at Thanksgiving or to order a side of fries with a favorite meal. These small thoughts, these moments of deliberation, can lead to much larger issues.

“Even if you’re not saying it to your daughter or son, but if you’re just talking about yourself negatively in front of them, they kind of take your ideas and use that as their expectations for themselves,” Scott continues.

Young people often internalize many of the things they hear, especially from trusted figures in their lives such as parents and guardians, mentors or other relatives. From comments on their own bodies, saying “I can’t eat that, it’ll go straight to my thighs,” to eating miniscule portions of food, children can be very aware of how their parents interact with and talk about food. While these comments may not cause adolescents to develop unhealthy eating habits, they can completely alter their perceptions of certain foods. They can also enable self-deprecating thoughts. Without parents realizing it, their seemingly harmless comments and habits can determine the subconscious outlook their children have both on food and their bodies.

“I think I’ve talked to a lot of people and a lot of my other girlfriends can relate that moms from a certain generation have a skewed way of looking at food and things like that. The way that my mom used to talk about herself [and] about the things that she ate [in a restrictive way,] influenced me to think those same things,” says ETHS student Diana Diggs*.

Unfortunately, comments aren’t the only way family makeup can contribute to abnormal eating patterns. Eating can be a very social activity and not having the structure that eating with others may provide can make eating a full, nutritious meal seem less important. As students grow older and become more independent with increasingly hectic schedules, there are less structures in place that promote healthy and consistent eating habits. With age, students have more autonomy over what they eat and when: they may become responsible for packing their own lunches, making their own breakfast or cooking their own dinner as opposed to having their parents or guardians complete these tasks for them. With less supervision, it leaves room for students to skip meals without any parental intervention.

“We don’t really have family dinner every night or family breakfast. So I think neglecting to bring people together, not holding people accountable and not being able to see what they’re eating can contribute. I mean, I would tell my mom I ate breakfast when I very clearly did not eat breakfast,” Scott, who has struggled with anorexia, explains.

Due to the diversity in every family routine, many families don’t sit down and eat meals together. However, it’s still important to check in on family members and strive towards eating together whenever possible. Family routines and meal norms can also be dependent on that specific family’s culture. Some people eat at different times, serve different courses and consume different portions. Food is cultural, and culture determines values. A family’s relationship with food often determines how an individual regards food and navigates their diet.

“Indian families and many other families around the world are huge, and so they also have a strong belief of not letting food go to waste. They’ll push family or friends to just eat their food because they don’t like the idea of food being thrown out when there was so much hard work and love poured into it,” Sammy Joseph, an Indian sophomore, explains.

Despite this, Joseph admits to having small disputes with family members over food. Sometimes, the intentions behind certain comments are unclear, which can create miscommunications.

“There was a point where I definitely took it the wrong way. I just thought she wanted me to stuff myself and I [would tell her,] ‘No, I don’t want any more. I’m satisfied with how much I ate.’ But over time, I eventually grew to understand that it wasn’t coming from any place of rudeness. She just wanted me to be well-fed,” Joseph describes.

Many factors, such as culture, connect family to food in ways that can be both negative and positive. However, it’s been found that families aren’t the only thing that can influence relationships to food—so can actual genetics. According to the National Library of Medicine, eating disorders have become increasingly linked to genetic factors. Originally, as the report states, they were solely caused by sociocultural factors. However, as humans have evolved, their neurochemical makeups have changed, leading to generational cycles of eating disorders. This study also found that age and developmental differences can contribute to these issues. It’s stated that in groups of 11-year-olds, there seems to be no genetic contribution to eating pathology and attitudes towards food. However, in the group of 17 year olds, over 50 percent of variance in eating patterns can be attributed to genetics. The theory is that “these findings may reflect an activation of etiologic genes during puberty.” Etiologic genes are essentially genes that can contribute to the contraction of a disease. While genetic makeup can absolutely be a factor, it’s important to keep in mind that anyone can suffer from an eating disorder, and family relations are not the only contributor.

Societal Influence

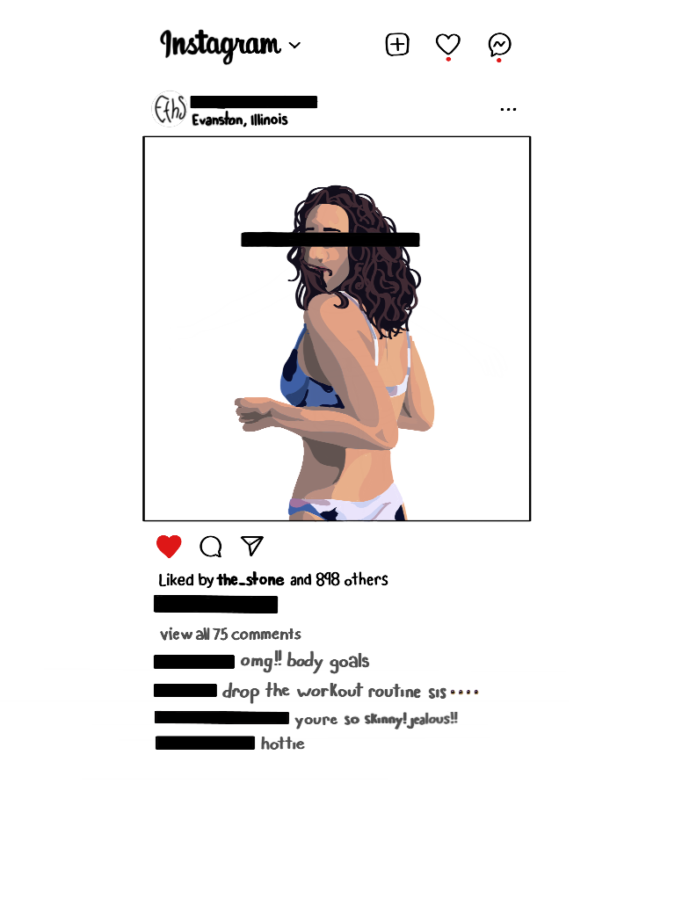

Videos explaining how to diet, showing off flat stomachs and thin figures fill student Stella Scott’s For You Page. With the right angles, lighting and the ability to edit out any perceived imperfections, social media posts, working alongside algorithms that push the kind of content that users show interest in, surround Scott, causing a downward spiral of comparisons with the “perfect” person constantly plastered on their screen.

“You’re seeing these videos, because they’re catered to you, and if you’re liking videos, with small girls who are so beautiful, dancing in bikinis, or you’re liking a video that’s like, ‘Oh, I didn’t eat today,’ then you keep getting these videos of these girls that are eating [less]. It’s just putting you in a worse and worse place than you were before,” says Scott. “I downloaded the app yesterday, and I had to delete it again.”

In addition to the consequences of social media algorithms, advertisements flood today’s world and target people’s interests very specifically. While advertisements were previously targeted to adult consumers, there has been a gradual shift toward reaching younger and younger audiences. Ads targeting teenagers can be incredibly harmful if they promote unhealthy habits to such a vulnerable and impressionable group. The media’s emphasis on diet culture and the push to appear a certain way conveys the idea that there is one way to live and look to teenagers who just want to fit in.

“I think [diet culture] used to be pushed more towards middle-aged women, but with the growing presence of social media in younger kids’ lives, I think they’re just exposed to way more than they used to be in the past. I definitely didn’t grow up with TikTok and seeing people dancing around in swimsuits, but I can imagine that has terrible effects for how an eight-year-old girl can view her chubbier body. I think it’s shifted from older [women] to teenagers,” says Scott.

This social media bombardment and constant media pressure to conform to the beauty standard confronts students at all times, even during breaks in the school day meant to serve as a way for them to de-stress. There is truly no way to avoid societal pressure when on a cell phone, and students are faced with the consequences of this endless cycle. In Wellness classes, which are intended to help students understand their own bodies and learn how to take care of themselves, students are still constantly reminded of how their own bodies compare to those of others.

“I give my kids in my classes, a five-minute social wellness break. It is absolutely silent. Nobody talks to each other. There isn’t any conversation. It’s right to your phone, so [the classroom environment has] changed. If I were to give my classes a five-minute social wellness break five years ago, it would be nothing but talking. Now we’re constantly, I mean multiple times a day, comparing ourselves to other people,” says Frank Consiglio, an ETHS Wellness teacher. “When we go on Tik Tok, or we go on Instagram, [and] you’re seeing the best version of people. Not just for young people, but teenagers and adults too, it’s hard to separate what’s real and what’s not real.”

Outside of social media, society begins to infiltrate a students’ relationship to food before they open up their phone. Fellow students and toxic relationships can worsen one’s view of food and exacerbate any food-related issues that may already exist. A student who may be self-conscious about their appearance or a student who has an eating disorder may find themselves constantly reminded of their internal battles and how others perceive them by the way their peers interact with them. Even unintentionally, the comments of other students can leave long-lasting impacts on struggling students or catalyze unhealthy relationships between someone’s body and food.

“I think that the biggest thing that I want people to know is that any compliment on someone’s body can be harmful, even if it’s something that you perceive as a compliment, like telling someone that they look good. You have no idea what kind of relationship they have with their body. I think a lot of the times when… I would go without eating for days, someone would tell me that I would look good. To me, I would equate that with, I should keep doing what I’m doing and so, I think people should never comment on how someone’s body specifically looks,” Diggs explains.

Comments with negative impacts aren’t always unintended, though. Bullying has not disappeared, and peers can be the most hurtful to one’s self-esteem and body image, especially when their comments are intended to harm another.

“I’ve definitely been called fat like many times,” says Scott. “I believe, if I never met [certain people], my relationship with food would be 1,000 times better.”

Regardless of the driving forces behind disordered eating, the most important stage to an eating disorder is the last, and sometimes hardest, step: recovery.

Support & Healing

With one hand on the door and the other holding her keys, ETHS student Kelly Kirk* was about to head out for the night when her mom stopped her. Eyeing the way the waist of Kirk’s jeans sagged loosely around her torso and her once tight-fitting shirt now hung limp around her ribs, her mom had no idea that her next words would cause Kirk to burst into tears.

Her mom saying that she looked ‘extremely skinny’ was the breaking point. For months, Kirk had been grappling with her anorexia on her own, but now she knew she needed support.

According to the South Carolina Department of Mental Health, only one in 10 people who are battling eating disorders receive support. This means that millions of people struggling with everyday eating, are left helpless. Without support, it is almost impossible to change day-to-day habits. However, building up the courage to say something and actually seeking support can be just as strenuous.

“I haven’t really ever sought support, but it was kind of just given to me. But I think it’s good to seek support. I also think the support ended up being good. I was just embarrassed and scared to be vulnerable,” says Littenberg.

Despite support being inherently ‘good,’ the journey to get there can often be limited by the stigma that often surrounds disordered eating. Dismantling this societal perception begins with education and awareness.

“I think that there could definitely be more [awareness] about misconceptions [accompanying eating disorders]. [For example], a lot of what people hear about is just anorexia, and they think people only eat less because they want their bodies to look better, which isn’t the case. It’s easy for people to jump to that conclusion, so I think there could be definitely more awareness about other types of eating disorders,” shares Rena Reed*, a student at ETHS.

Not only is misinformation regarding eating disorders common, but falsification about eating habits alone is also potent throughout modern culture. In recent years, students have criticized the Wellness curriculum for upholding negative stereotypes regarding calories and nutrition. Now, Wellness teachers aim to reverse this trend, reworking the way they approach content involving nutrition.

“I think people focus too much on calories. Whenever somebody hears the words calorie and fat, they think of it as a negative term. That’s not just [at ETHS]; that’s really everywhere,” explains Wellness teacher Frank Consiglio. “I think what we need to look at is how food works as fuel. If that’s the focus of our teaching, then I think that some of those misconceptions can be managed.”

Well-thought-out, comprehensive education regarding both the process of eating and eating disorders is essential because many of the driving forces behind disordered eating are rooted in cultural mindsets and societal perceptions. However, educational precautions and interventions are not the only tools that are available to students struggling with disordered eating.

Following her mother’s confrontation, Kirk began regularly meeting with doctors and nutritionists in order to regain a healthy relationship to food.

“I would get weekly visits, and they would weigh me, and I had to pee in a cup for them. Then, I had to get tested for all of these different sensitivities that I could have possibly gotten because I couldn’t eat anything without feeling sick at that point, so they drew a bunch of blood from me. I had to try and gain weight, and I didn’t always do it, because it’s just hard to get your body to work again.”

There are several resources and centers in Evanston with a similar approach to eating disorder recovery. While seeking support from a doctor or medically trained professional is crucial for health factors, it can also be a difficult process for patients and may feel impersonal. Consequently, connections and relationships with loved ones are also integral in recovery. Friends and family have an element of personalization that people in healthcare settings don’t possess.

“My friends really got me through a lot of it, because they checked in on me but they also still treated me like I was normal, which made me feel more human than I felt when I was at these doctor’s appointments, because the only thing that mattered [to the doctors] was my weight,” Kirk notes.

Just like personal relationships largely influence the formation of eating habits, intimate friendships can inversely serve as sources of nourishment toward recovery, and if there’s one common theme amongst the emergence and recovery of disordered eating: the little things go a long way.

“I think a lot of my friends knew about the things that I was going through. It was easy for the people really close to me to encourage me, and they continue to invite me to go places, getting lunch and stuff like that. Having my closest friends invite me [made me feel] more comfortable eating in front of them and made me not worry so much about how I look in front of them,” Diggs reflects.

Valued friends are a key component of healing, and for many people, it’s easier to confide in a friend than a parent. However, it’s essential that family members act as a source of support as well.

“My relationship with my father was really helpful. My dad was really looking out for me and would check in. Once he realized there was an issue, he would check in all the time to make sure I wasn’t like falling down that path again. He really supported me a lot. He was so aware of what was happening, and he cared so much about me. He’s such an awesome man,” says Littenberg.

Whether it’s a trip to the doctor’s office, a hug from a good friend or eating together as a family, support looks different for everyone. If you or someone you know is struggling with disordered eating, the national eating disorder helpline is (800) 931-2237.