2,580 miles away from her home in Medellin, Colombia, Maria Gomez stepped into ETHS for the first time in 2021, a junior in high school. As Gomez made her way through the unfamiliar, winding hallways of ETHS, surrounded by students that had known each other since freshman year, she couldn’t help but feel out of place.

Gomez wasn’t just 2,580 miles away from her home; she was 2,580 miles away from her culture, family, friends and even language. Feeling disconnected from her community, Gomez sought out a space at ETHS where she could engage with people who shared a similar background with her.

It was while in her math class—GANAS Algebra 2 for self-identified Latinx students—that Gomez finally experienced that sense of belonging.

“I felt like I belonged in that class and that I had more connections, in terms of culture,” Gomez said. “ I wasn’t the only one that was in my situation, so that was also good, because you get to meet new students that are also speaking in Spanish or that are also Latinos. There were people that didn’t speak Spanish, but they had our same roots. And that wasn’t a problem at all, because we are all part of the same culture. We felt like a family.”

Unlike a typical section of Algebra 2, GANAS is listed under the course selection guide as “intended to support students who identify as Latinx.” Students learn the same material and explore the same concepts, but the class is composed exclusively of students and a teacher who identifies as Latinx.

“My personal hope in teaching the GANAS courses is that I am able to provide opportunities where my students feel empowered and motivated as well as creating a space where students can show up as their authentic selves,” Raquel Lopez, who teaches GANAS, said. “I hope that in having Latinx specific math lessons that include real world data, we can have conversations where students feel seen, validated and appreciated as Latinx folks.”

GANAS Algebra 2 is just one of the six racial affinity classes that ETHS offers for Black and Latinx students. Superintendent Marcus Cambell explains that the combination of them—GANAS Algebra 2, Precalculus and AP Calculus AB for Latinx students and AXLE English 2, Precalculus and AP Calculus AB for Black students—were developed in an effort to relieve performance anxiety for students of color in white-dominated spaces and create a pathway to AP-level courses.

“A lot of kids of color talk about feeling very isolated. And so we think, ‘How can we provide an opportunity to reduce performance anxiety and follow the research on stereotype threat and provide a different, more familiar setting to kids who feel really anxious about being in an AP class?’” Campbell said.

In recent months, these courses have sparked national controversy and discussion, even becoming the subject of an editorial by the Wall Street Journal entitled “Progressives return to the days of ‘separate but equal’ education.” People have hid behind computer screens on Facebook groups and Twitter threads to compare these classes to modern-day segregation, resulting in pressure on the school to discontinue the practice. However, ETHS continues to stress the importance of classes like these in creating safe spaces for students of color.

THE EXPERIENCE

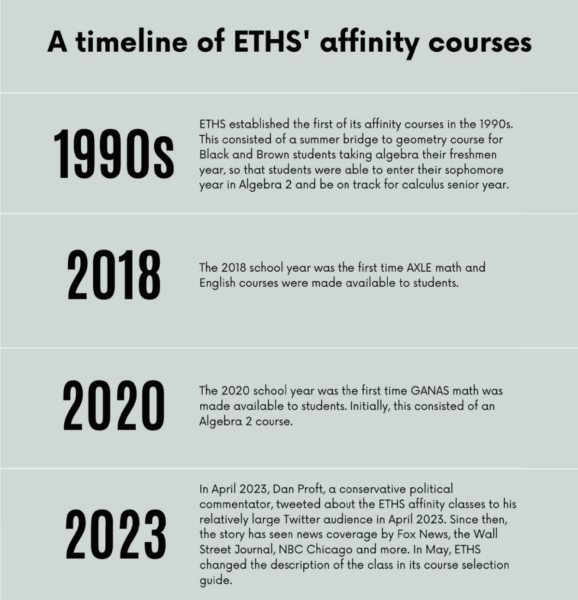

Despite only recently making their way into mainstream news, affinity classes are not a new concept at ETHS. Over two decades ago, in the 1990s, an Algebra teacher noticed a pattern among the freshman classes: few Black or Brown students entered the high school in Geometry, preventing them from taking AP Calculus before graduation. Recognizing the importance of AP Calculus as a gateway to college, this teacher, alongside ETHS administrators, established a summer geometry program for Black and Brown students going into their sophomore year.

“If you come to ETHS taking Algebra as a freshman, you take Algebra, Geometry, Algebra 2, Precalculus and that’s it. So, by virtue of the tracking situation in District 65, we had very few Black and Brown students who were ever entering the high school in Geometry, which is kind of a key to getting access to the AP Calculus math class,” Assistant Superintendent of Curriculum and Instruction Pete Bavis said. “So, that was the origin story: a teacher noticing a pattern, saying this isn’t cool, picking up a phone and creating a sound program.”

Today, more than 20 years later, teachers continue to play a large role in the development of these courses. In 2018, Abdel Shakur, who teaches AXLE English 2, took on the class in hopes of fostering a supportive community that could academically and socially challenge Black males.

“From my experiences as a student and as a teacher, I know that there are barriers for Black males to be involved in all aspects of an academic class, and the idea that we could create a space where all those spaces we’re going to be open was really exciting to me,” Shakur said. “When I think about this particular class, which is a writing workshop class, a big piece of it is a focus on writing, writing identity, writing skills and also writing community. So, that idea of being able to establish a writing community that was really supportive and really challenging to young Black males excited me as a writer, as a teacher and even as a parent. That’s what got me going,” he said.

Shakur’s intention to push students is present in his approach. Junior Omar Pryor, who took the class sophomore year, felt Shakur made an effort to challenge young men who might have otherwise been overlooked by the education system.

“There were more of the kids that maybe some teachers may have just like ‘Oh, I guess they’re just not going to get this. This is the type of student they’re going to be in that class,’” Pryor said. “Mr. Shakur didn’t really accept that; he pushed everyone to make changes and be the best possible student that they could be.”

Similarly, GANAS, the Spanish word for ‘a desire,’ was named to encourage students to have a desire to be better versions of themselves—a message Lopez, who teaches GANAS, relayed from the first day of now-senior Sophia Robles’ GANAS Algebra 2 course her sophomore year.

“She explained what the class was for as well as what the goal was, and she actually told us she named it GANAS because it means a desire,” Robles said. “So, in her explanation, this class is for you guys to have a desire to do better, to say more and be more than what you’d normally be in other classes. She also said that this was a safe environment for us to get to know each other, as well as learn the same math that everyone else was learning.”

Another key element of the affinity classes is a strong line of trust between families and their student’s teacher. During the course selection process, teachers take the time to personally call and email with prospective students and their families—sanctioning clarity and connection before the year has even begun.

“I think that it’s important to establish trust with the students, and especially with families, when we’re taking a different approach to the way we’re constructing our class communities,” Shakur said. “So, I need everybody to understand why we’re doing it and what exactly we will be doing. So in the end, it kind of makes all of our jobs easier if we’re connected and we understand what’s happening.”

Had it not been for the phone call Lopez made to Robles’ mom freshman year, Robles would have never found herself in the class community she now refers to as “her closest friends.”

“Ms. Lopez personally called all the kids that she thought would be interested in the class. She basically explained the class as sort of a shared space with students who identify as Latino, Latina or Latinx. And I thought it was a pretty cool opportunity,” Robles said. “Two years later, GANAS has been a really positive influence in my life. I’ve made so many new friends, and I have a teacher that I can go to in any situation.”

While some AP classes have historically fostered an unwelcoming atmosphere for him, graduated student Evan Berrato, who took AXLE English 2 and AP Calculus, felt the AXLE space was refreshingly inclusive.

“A lot of the time AP classes are not inclusive at all, and it was good to have a higher level of education within my community,” Berrato said. “I have been in these spaces where they’re not very welcoming or inclusive at all.”

In Berrato’s experience, there was no need to draw attention to the fact that they were in an affinity class—the sense of camaraderie was present from day one.

“It wasn’t something that we had acknowledged because we didn’t have to,” Barreto said. “We had already looked around and saw ourselves in our classmates and been able to build community without having to mention why we’re all here gathered in this room because that’s how our culture works. We are able to just relax around each other, and we didn’t have any need for a statement.”

Other students shared a similar sentiment with Berrato; the affinity spaces felt less like a classroom and more like a community.

“When you go to a normal class like English, you go there just to learn. When I go to this class, I feel excited to learn. I don’t feel like I am being forced to learn,” senior Wendy Morales, who has been in GANAS Algebra 2 and Precalculus, said. “I feel like I have the privilege to learn and be surrounded by people that share a common identity with me and can understand what I’m going through on a different level.”

While learning the curriculum is the main priority of the course, both the teachers and students make an effort to recognize and embrace the cultures present in the classroom.

“They wanted to get to know us better, and we would talk about things that we had in common, like that our families do or foods that we eat,” graduated student Rowan Luzzi, who took GANAS Algebra 2 and Precalculus, said. “So, it was easier to connect with the teacher and other students, and it was very clear that they cared about us. Everyone seemed excited to be in a class, even if they didn’t like the subject because we all got to be in a space that was created for us.”

With that recognition of culture also came a recognition of struggle.

“It was different from a regular English class. We were able to talk about problems in the Black community, but it was also a good English class in terms of the actual subject,” Pryor said.

“There was some understanding of the difficulties that we face in the school system as Latinx students,” Luzzi said. “So, I think our teacher was better able to talk to us and like to work with us to learn math and like to get past problems.”

Due largely in part to their shared identities and experiences, affinity class teachers are able to simultaneously act as mentors to their students. From lunches to class celebrations, these teachers take the time to connect with their students on a personal level.

“The teachers don’t just teach us math. Like any teacher, they go over the class work and host AM support and all of that, but I’m also having lunch with them, and I was still going in to meet with my teacher from last year,” Morales said. “I still turn to my teachers for help when I need it, even when they’re not my teachers anymore. They are connecting with us on a different level; they’re telling us about their family, their journey and what it means to be Mexican-American in a field like math that we’re often excluded from.”

Again, this deeper level of connection appears when recognizing one another’s joint struggles.

“These teachers, they were in your shoes once, so from their mistakes and their struggles, they can give you tips on how to continue on even when things get hard—when you feel segregated, when you feel discriminated against, when you feel insulted,” Juarez said. “And so, I feel not only do these classes teach you, they push you to go after that harder class that you really didn’t think you could do or take this AP exam that you just didn’t think you can do, or go after this program during the summer that you didn’t think you could do. They’re just another support system that is at school.”

Students whose first language is Spanish especially benefit from the shared identity with their teacher. By being able to ask clarifying questions in their first language, these students are able to gain a deeper understanding of the material that wouldn’t be possible in a typical classroom environment.

“At the beginning, I didn’t speak English in a professional way, so I spoke with the teacher in Spanish, and she responded to me in Spanish, but then she changed to English,” Gomez said. “And that’s crucial when you’re learning math because I need to know what’s going on, and having someone that can explain to me in my language was really helpful.”

While Grace Juarez had historically been in English-only math classes, the ability to switch between languages brought about new confidence in her skills.

“I just felt comfortable in that class. English is not my first language, and having the option to ask questions when I couldn’t think of how to properly state it in English brought more comfort and more confidence within my abilities,” senior Juarez, who took GANAS Algebra 2 and Precalculus, said. “I noticed, after a year went on, how much confidence I was having with questions, my strengths and my weaknesses. It’s an environment that feels like home.”

Juarez is now enrolled in GANAS AP Calculus, but before participating in her first affinity class, she never even considered the possibility of taking that class in high school.

“If these classes weren’t to exist I know I wouldn’t be able to believe in myself as I do now. These classes opened my mind so much, they brought so much knowledge and so not only growing academically, but with these classes, if they didn’t have these classes, I wouldn’t be taking the harder AP classes that I would be taking,” Juarez said. “I never thought that I would be taking calculus, but I wouldn’t be pushing myself more to take it if I weren’t to have this class or these teachers.”

THE RESEARCH

The experience of solidarity and safety within affinity classes isn’t exclusive to student accounts–there is also a significant amount of supporting research proving the benefit and occurrence of these experiences. Like in any academic field, research in education policy shapes data, and data shapes decision making. Decisions then shape norms, and norms shape the way we behave. This behavior is represented clearly within classroom environments, where peer behavior then shapes the learning experience for all students.

Dr. Terrell Morton, an assistant professor of identity and justice in STEM education in the department of Educational Psychology at the University of Illinois Chicago, highlights how these peer norms translate outside of the classroom and into society.

“Peers play a really big role in how a person understands who they are; in terms of how a person understands their own value, in terms of a person understanding their own intelligence, because peer pressure, peer groups and peer norms are really big for how people move in societies,” he said.

In addition to peer behavior, Morton recognizes content (what students are learning), power dynamics (teacher versus student), and variance of experience (socioeconomic and familial backgrounds) as other key components of the classroom experience.

For many students of color, at least one of these components works against their success in traditional classroom settings.

The content learned is generally produced through a westernized lens in which narratives are told through a eurocentric, white perspective and exclude the experiences of people of color. The traditional relationship between a teacher and student is authoritarian and does not center on the fact that every student in a classroom experiences the world differently depending on their backgrounds and identities. This variance of experience can pose social and educational challenges if the classroom space is not systemically built to accept and accommodate a wide range of students.

These classroom challenges can then lead to students experiencing performance anxiety, a feeling that they don’t belong or academic underperformance. TaRhonda Woods, ETHS teacher and advisor for Students Organized Against Racism (SOAR), elaborates on how affinity spaces are supposed to combat this.

“We need to think about what it means for a Black student to be in these kinds of higher level courses and to not feel like the teacher really sees them as being capable or competent. One of the things that I’ve heard students who have been in that [affinity] space say is that, ‘She gets me, she understands me, she allows me to be myself but then also has high expectations of me, that pushes me to be able to be the thinker and the learner that I know I’m capable of being,’” she said.

Part of the reason this structure is in place is because, when developing ETHS’ current GANAS and AXLE courses, Campbell and Bavis drew from previously established research and precedent.

“We use the research from Claude Steele, who writes about performance anxiety and stereotype threat, and Sian Beilock, who writes about performance anxiety,” Campbell said. “A lot of schools have experimented with what would happen if we put a group of similar identifying people together to bring that performance anxiety down.”

One of these school districts Campbell took inspiration from—the Tucson Unified School District of Arizona—implemented a Mexican-American studies program in 1997, with the goal of decreasing the dropout rate for Latinx students. Immediately, the district saw significant increases in standardized tests and graduation rates for students in ethnic studies courses, but this didn’t stop the controversy. In 2012, the program was cut after the Arizona state government threatened to take away $14 million dollars of the district’s funding; pushback to racial affinity classes is nothing new.

Dr. April Warren-Grice, CEO of Liberated Genius, which offers “current relevant pedagogy professional development for equity and justice” investigates the history of research regarding affinity spaces within educational settings in “A Space to be Whole: A Landscape Analysis of Education-Based Affinity Groups in the U.S.”

“Affinity in schools is not new. We are structured to operate in affinity relative to grades and subject matter. Racial affinity can support all teachers and educators in understanding how they have been harmed by racial oppression, how to heal from that harm, how our systems are designed to perpetuate that oppression, and how their racial identity connects to what actions they can take to transform systems,” she writes.

Through her research in association with the National Equity Project and the Black Teacher Project, Warren-Grice emphasizes the importance of affinity spaces not only for students of color, but also for educators of color and the communities that schools serve.

“By focusing on the needs of educators of color, racial affinity groups generate positive results such as increased retention rates (Education Trust & Teach West, 2019). Racial affinity groups also affirm participants’ goals, values, racial identity, and humanity. They provide informal and formal mentorship, create community and supportive relationships, and in some instances compensate educators financially for engaging in professional development (Bristol, 2016),” reads the study.

Within academic research, affinity spaces are often referred to as “counter spaces,” that, as Morton explains, are designed to “counter” the dominant classroom narrative where students of color are often underrepresented.

“This counter space is being intentional to bring people of that identity together so that they are not only in the numerical majority, but they can begin to understand commonalities and experiences, both the successes that they have, but as well as the challenges they face. They can begin to develop and identify specific resources and navigational skills as they learn how to cope with the different stressors that they may face in those dominant, normative spaces,” he said.

Woods also highlights how affinity spaces counter traditional educational norms via building legitimate connections through culture and student validation.

“When we think about what education has done and how it has functioned, and the ways it has been designed, there have to be some acts of dismantling and disrupting those narratives…It is essential for students of color to have spaces where they are seen, where they are heard, and where they are validated,” she said.

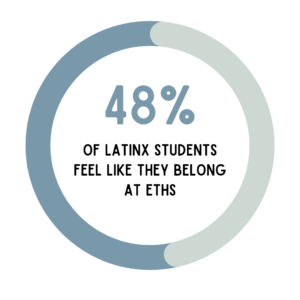

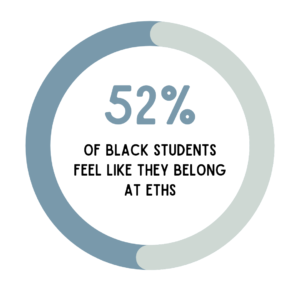

During the 2021-22 school year, according to the ETHS Wellbeing/Climate survey administered in February 2022, only about 52 percent of Black students and 48 percent of Hispanic/Latinx students felt a sense of belonging at school.

For Pryor, the sophomore English class for Black men offered a sense of belonging that was difficult to find in his other classes.

“There was just a huge sense of community; it was a lot of fun,” he said. “It was different from regular English classes, and we were able to talk about problems in the Black community…there was a real brotherhood.”

THE CONTROVERSY

The first educational affinity space dates back to about 1878, when Black teachers in Georgia asked their administration for the same pay as their white counterparts–this controversy sparked the formation of organizations specifically for Black educators to advocate for their rights and strategize the support of their communities. Dr. Vanessa Siddle Walker’s 2018 book, “The Lost Education of Horace Tate,” identifies three main pillars of affinity spaces that grew out of these first initiatives started by Black educators: aspiration, advocacy and success.

These initial affinity groups created the framework for classroom affinity spaces, which have also been around for many decades, but didn’t begin to gain popularity until the early 2000s and saw even more growth later in the 2010s. Essentially, affinity spaces and their guiding principles are not new, and their goals have not shifted since the creation of Black educator affinity groups in the late 19th century.

But beginning in 2023, 145 years after the formation of education’s first affinity group and more than 20 years after the first affinity class was offered at ETHS, the media took notice of ETHS’ use of affinity spaces within the yearly course request guide. Headlines from historically right-wing news sources include “ETHS and Race-targeted Math Classes” and “High School Accused of Offering Race Segregated Math Classes Slapped with Civil Rights Complaint.”

Articles comparing the use of affinity spaces to segregation demanded that ETHS remove affinity courses from its course offerings. News outlets from as far away as the UK, such as The Spectator, suddenly expressed strong feelings in the language used to describe the courses, referencing the italic text underneath each affinity course description which read “this course is restricted to students who identify as Latinx,” or “this course is restricted to students who identify as Black males.”

Following the harsh pushback, ETHS did end up removing the term “restricted” from their course descriptions, replacing it with “while open to all students, this option section of the course is intended to support students who identify as ‘latinx’ or ‘black.’”

“That changed because what was written doesn’t reflect the practice..It’s just not restricted. The courses are open to everyone. If push came to shove and you look at the master schedule, and a kid needs calculus that period and there’s nothing else that works and that kid is white, of course we’ll put them in the affinity class,” Campbell said.

For ETHS senior Sophia Robles, the initial language used to describe the course seemed easy to misunderstand, and she expressed relief that the course guide was edited.

“I thought [the news] had probably misunderstood the class,” she said. “I think the wording of the [original] description made it hard to understand. I don’t think the class is modern segregation or whatever was said in the article, just because we all chose to be in the class.”

Olivia Catayong, an ETHS senior who was a student in the all-women’s engineering class her sophomore year, expresses similar feelings to Robles.

“What was the pushback even for?” she said. “I don’t know why people are so mad. You’re choosing to be in that space, right? It’s not segregation, because segregation is forced. That just seems so clear to me.”

For many students, this—students choosing to be in these spaces, not being forced to be—seemed to be the primary misunderstanding between conservative media and the true purpose of the affinity classes. Students are choosing to be in these spaces, and no one is forcing them in or out of the class.

While graduated senior Nasir Sims chose not to enroll in any affinity classes during his time at ETHS, he has participated in other affinity spaces outside of the classroom and recognizes the value of being comfortable in your space.

“I personally didn’t take an AXLE classes,” he said. “It just didn’t feel like something I needed. I have felt very fortunate and comfortable throughout my high school experience, but there are people at ETHS who don’t go through the same thing. I think it’s important that ETHS opens the door to this kind of positive experience for other people.”

“We choose to be there. So, for me, and I know for a lot of students, things sometimes go wrong, and we literally fight to be in these classes,” Juarez said. “During the course selection, we have to be chasing after our counselor, just to make sure that we will be in that section, because it has impacted us so much. We’ve created so many bonds with other students. That’s where most of our friendships come from, so it’s not felt as segregated from other classes.”

News sources have voiced concerns over the difficulty of the curriculum, but from Juarez’s experience, the GANAS section sometimes tackles harder concepts than other sections of the same class.

“I’ve had conversations with friends that are in the non-GANAS sections of our class, and sometimes our section is taking it even further. We’re learning the harder stuff. Our teachers talk about how we have to, as minorities, push even harder to get to these same levels as other people,” Juarez said.

Berrato feels that these complaints are eerily similar to attacks on critical race theory.

“I mean, for the most part, I see a lot of attacks coming for critical race theory. It’s kind of random and funny because, [in affinity] classes, it’s not going to be critical race theory at all…we just had like a short mention of ‘hey guys, like we’re all Black.’ Those types of attacks on classrooms and curriculums are so uneducated,” he said.

Dan Proft, a conservative political commentator, tweeted about the ETHS affinity classes to his relatively large Twitter audience in April 2023. The tweet references the language used in the course guide describing affinity space calculus. “Neo-segregation is the absurdity of identitarianism taken to its logical end,” wrote Proft.

‘Neo-segregation’ is a term referenced by many right-wing critics, implying that affinity classes are perpetuating a level of discrimination within schools.

“I’ve heard people say it’s reverse discrimination. I’ve heard people say it is reverse racism. I heard people say it’s new forms of segregation I’ve heard people say that it causes other people, not of those identity groups to feel shamed about their stories. And my response to all of that is, if we’re truly invested in having a society in which all people feel welcome, in which all people feel empowered, and in which all people believe and have access to the resources to be successful, then we, as a country, have to account for, for our very problematic history,” Morton said.

“I believe people make those arguments because affinity spaces require additional resources. And one of the things that I’ve learned both through my research and just through life is that people who have a lot of power and people who have a lot of resources don’t like to give up their power and their resources. So they’re making these arguments so that they can keep their power so they can hoard all of the resources. What others are trying to do is say, ‘Hey, that’s not fair.’ How do we actually disperse power? And how do we disperse resources?”

Despite the controversy fueled by conservative media, ETHS affinity classes continue to function on their guiding principles and foster spaces of learning and solidarity.

“That solidarity is important when we start trying to challenge our ideas and perceptions of the world. It’s not solidarity to just agree about everything, but solidarity as a sense of safety to know that we’re exploring here to lift each other up and not necessarily be competitive or criticize each other,” Shakur said. “We know what we’re doing, why we’re doing it, and we are continually reflecting on it.”

‘THESE ARE MY PEOPLE’

After hearing stories about the joy and community found within affinity classes from past students, ETHS junior Sally Beckley decided to register for the GANAS Pre-calculus class. Beckley’s choice to enroll in the class reflects a wide array of her values; beyond connecting with her Puerto Rican culture at school, she is hoping to increase Latina representation in the STEM field post high school. She looks forward to walking into class on the first day of school and feeling the sense of belonging and connection that her friends had described when reflecting on their experiences in the space.

“It’s not like I have had a harder time in these classes where I see less Latinos, but it is definitely going to be a better experience to be with all Latinos,” Beckley said.

“Like, oh my god, these are my people. We all have something real, we have a connection and now we have an empowering space.”

David Berman • Dec 14, 2023 at 1:49 pm

A question: can the Evanstonian obtain data on AP test performance for GANAS and AXLE students in comparison with their peers?

It would be interesting to know and might diffuse a lot of the heat that’s been generated.

David Berman • Dec 14, 2023 at 12:29 pm

Alum Class of 1969 and Evanstonian reporter and Managing Editor.

I can’t believe we’re going backward on the promise of a high quality integrated education for all.

While I welcome the improved sense of belonging and academic success participants experience the further disintegration it inherently produces will accelerate the decline of the American experiment.

James • Nov 26, 2023 at 2:38 pm

You spelled Colombia wrong…not a good look considering the subject matter…

Leah Piekarz • Sep 6, 2023 at 2:50 pm

This story was excellent. Well done, Evanstonian!