Eyes on safety

Senior Gabi Burnett was just nine years old. It was 2014, and she was at the St. Joan of Arc annual carnival, running around with her cousins as the sound of children screaming on rides echoed in the background, when a cop stopped her and cursed the group out.

“I’m shaking, I’m nervous, I’m sad; I don’t like being talked to in an aggressive tone, and he was cussing me clean out,” Burnett said, reflecting on the event. “I’m still a kid.”

This wasn’t the first time Burnett had experienced an abuse of power at the hand of law enforcement, but as the cop continued to grow more and more aggressive, it was the first time that she truly felt like her livelihood was in danger.

“There’s certain things [police officers] really can’t do being in a position of power— especially being in a position of power—where they’re able to defend themselves, and I can’t. If they feel like somebody is threatening [their] livelihood, [they] can handle it; I wouldn’t be able to at the age of 14, 13, 12, nine,” Burnett said. “I understood at that age that if they wanted to, they could end me, if they felt like they were within their rights. But, being a Black kid in America, I was definitely scared of that when I was younger, so when they used to talk to us like that, I just couldn’t do it.”

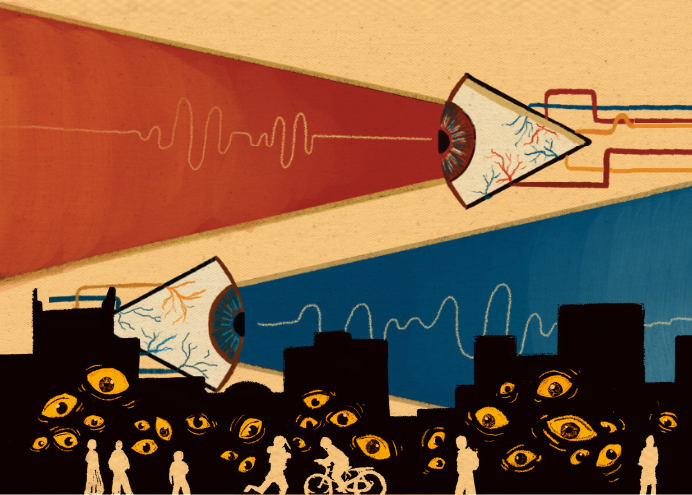

Nearly ten years later, that police presence continues to be a constant source of anxiety for Burnett, both in the community and even while at school. The over-surveillance and disproportionality in the power of law enforcement is present in every aspect of her life—whether a result of SROs roaming the hallways at ETHS or cops questioning her on the street.

“There are a few police officers that I have the utmost respect for, but with the establishment as a whole, my heart drops wherever I see a police car,” Burnett said. “Even if I’m not even doing anything, if I’m walking down the street, no matter what, I’m going to flinch. Is that a good thing? No, but it is my sad truth.”

Burnett isn’t alone. Police brutality and misconduct has always been an issue in America, but since 2020, there has been a movement both nationally and locally in Evanston to reevaluate the role of police and the methods in which residents of a city are kept safe. COVID-19 saw the rise of youth gun violence in the community, and for marginalized students, discipline practices often feel like a gateway to prison. Making their way through day-to-day life, ETHS students are forced to constantly be aware of the intersection between their identity and safety—at the school, in the community and during any interaction with authority figures.

On May 25, 2020, as ETHS students opened their Chromebooks to yet another day of Zoom classes and quarantine, three words changed the trajectory of not only the next few hours, but years to come. That day, following 46-year-old George Floyd’s arrest over the falsely-suspected use of a counterfeit $20 bill, Minneapolis Police Department Officer Derek Chauvin pinned Floyd down and knelt on his neck for nine minutes, as Floyd called out “I can’t breathe,” urging Chauvin to recognize his humanity. Five minutes later, Floyd was pronounced dead, and footage of the video was released for the world to see.

“In some ways, [George Floyd’s death] made me look at things differently, and in other ways, it didn’t, just because, from a young age, I had that conversation with my dad about how to act around police and what it meant to be a Black kid in this world,” ETHS alumni Aidan Wright* said. “But, it was the first time I actually saw that level of abuse happen.”

“[Floyd’s death] opened my eyes to the actual violence people experience,” Black senior Aliyah Washington* said. “I knew pre-2020 that there was this thing called police brutality, but I had never seen it before.”

While police presence was always a source of injustice for the Black community, the combination of much of the population being at home during quarantine and the increased prominence of social media as a tool to spread information rapidly sparked a movement both locally in Evanston and nationwide. In that moment, the injustices that had too frequently been swept away from the public perview were on the screens of nearly every American.

According to the Pew Research Center in July of 2020, of Black social media users, 76 percent felt the use of these platforms helped give a voice to underrepresented groups, 77 percent felt it highlighted important issues that would otherwise not receive a lot of attention and 82 percent felt it was effective in creating sustainable social justice movements.

“[The protests during 2020 were] a very interesting time, because everybody was chronically online, and that’s where most people got their media from. So, most of the information that I got was from social media, and I’d see how widespread the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests were. And then, at the height of them, a lot of people around me were going to the protests, so I had joined a few of them,” Washington, who was in eighth grade at the time, said.

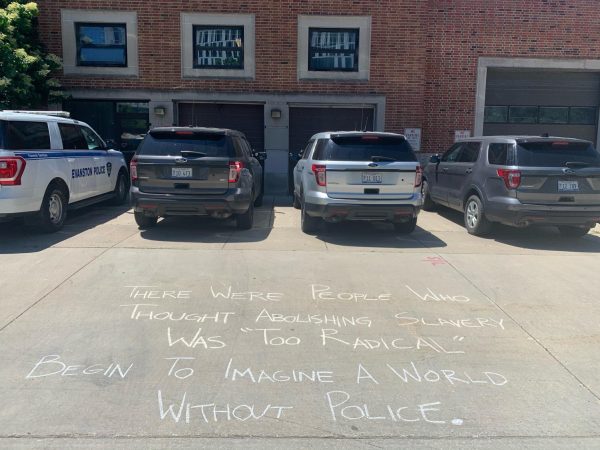

Over the following months, the streets of downtown Evanston flooded numerous times with protestors that sought to demand justice for those that had died at the hands of law enforcement. Signs reading ‘I can’t breathe,’ ‘No justice, no peace,’ ‘To serve and protect who?’ and other phrases became catalysts to demand change and advocate for reform. Just as these protests occurred in Evanston, they took place across the country.

“It felt weird to not have much of a say when I was seeing so many other Black people getting hurt,” current junior Dhaymian Price said.

During this time period, tension between protests and law enforcement skyrocketed. When Burnett was skateboarding through parts of Evanston in June, she went past an area blocked off for a protest. Burnett wasn’t a part of the protest—she didn’t even go into the area—but this still resulted in another verbal attack by police.

“Police were blocking off this part of Evanston, and I was skating by and got yelled at because there’s a protest going on. I was just skating,” Burnett said. “I just don’t have a good history with police.”

Later that year, in August, the movement struck even closer to home after Jacob Blake Jr., a lifelong Evanston resident with deep roots in the community, was shot seven times by police officers in Kenosha in front of his children and left paralyzed.

“This is 2020. And for you to think that shooting a young man in the back seven times is working for Kenosha’s police department, it is not. But I also don’t want you to think this a rogue officer, either. See, this is where the systemic [part] comes in,” Justin Blake, Jacob Blake’s uncle, told the Evanston Roundtable on Oct. 5, 2020.

In Illinois, the Safety, Accountability, Fairness, and Equity-Today (SAFE-T) Act from 2021 offered new standards for police force, expanded the use of body cameras, created a statewide decertification process for officers, required training on topics including crisis intervention, de-escalation, use of force, high-risk traffic stops, implicit bias, racial and ethnic sensitivity training, emergency response and more.

“With the SAFE-T act and the state mandates, there is an abundance of training that’s mandatory, and I think that’s a good thing, especially towards reform, accountability and transparency,” Schenita Stewart, who was instated as Evanston’s Chief of Police on Oct. 10, 2022, said.

Within Evanston specifically, the police department focused their attention on the intersection between mental health and crime.

EPD Commander Ryan Glew reflects on the ways in which the department has grown in its response to the criminalization of individuals going through crises.

“There was not a conversation 10 years ago, where a law enforcement officer was sat down and said to them, ‘You’re going to get a mental health crisis foisted upon you; prepare. Here’s the training; here’s the money.’ Instead, we got the problem, and we didn’t get everything else. We didn’t get the training,” Glew said. “And here we are, in today’s day and age, and there is a lot more contact with people suffering from mental illness on the street than there was before. It also came to be in the forefront of people’s minds around in the wake of the George Floyd instance.

“It’s hard to untangle, so as an agency, like many law enforcement agencies across the country that have people suffering from various mental health crises on the street, we are looking to see how we can evolve our organization, our response to better be prepared, maintain traditional police services and serve that community. We want to effectively learn from past mistakes, learn from best practices and go forward.”

Rather than reflecting on the events of 2020, Stewart instead looks at the department’s performance over the past year in terms of deterring crime and emphasizing community outreach.

“I don’t live in the past; I’m all for the future and what I do as a leader. What I will say is, I evaluate every position in the organization to see the relevance and the importance to the community, and we’ve shown improvement for this past year,” Stewart said. “We’ve seen our impact not only on the high school, but the surrounding community and businesses around the high school. And so, if I were to get to the conclusion of this first year in office, and there were some issues that need to be addressed, I would have addressed them, but thankfully, I didn’t have that situation.”

Stewart also feels that more people need to take the time to recognize the work of individual officers.

“I think sometimes, just in society, we tend to look at a lot of negative things that happened in the past, and I’d rather appreciate what’s happened in the last year or look at what we’re getting done in the future,” Stewart said. “I am our cheerleader for my officers, and I’d appreciate it if sometimes people in the public would sit back and say, ‘Man, I really appreciate this, this and this that those officers have done,’ and not think about a time when everything was negative.”

Before Stewart began her tenure, as local police departments began to implement new procedures and practices, the city began to look at the justice system from a restorative lens. After instating its Reimagining Public Safety Committee in August of 2020, several ordinances were passed to keep residents out of the court system.

“We have moved to make local ordinance violations for certain felonies and for certain state laws, and that allows us to locally adjudicate those issues rather than sending it out to the traditional court system, which, again, I can’t say that the city has been great at restorative justice, but bringing those changes allows in the future, and even now for us to start to enact more restorative justice practices, particularly for younger folks by having these local violations that mirror state law,” Eighth Ward Councilmember and Reimagining Public Safety Committee member Devon Reid said.

Furthermore, the committee wanted to keep the number of traffic stops to as few as possible—prompting them to evaluate the need for interaction with police officers after minor infractions.

“There have been a number of changes, recommendations that have been put forward, some of them are coming down the pipe now,” Reid said. “One of them early on was that we need to change the way that we conduct traffic stops, and that, for traffic stops that are minor violations, such as a tail light being out, that the officer would let the person drive home after the stop anyhow. We decided that we can just mail these out to people or figure out an alternative way to help folks and to alert folks.”

Despite these efforts to change police practice in Evanston, students continue to experience profiling at the hands of law enforcement.

“It’s not surprising anymore when I’m at 7-11 [with my friends], and a cop pulls over, or rolls down the window, to ask us what we’re doing,” Wright said. “I never see it happen to any of my white friends, but whenever it’s a group of Black dudes, it’s like they get an alert to go check us out. We’re never doing anything, and I have to think—no, I know—that if I wasn’t [Black] I would probably be left alone.”

Thus, Wright never can allow himself to be off guard while in the community; there’s always a worry that he could be at the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong police officer.

“It’s something I always have to think about. I can’t get away from the assumptions people have. I don’t wear stuff that draws attention, and I try to seem as less Black as I can when a cop is talking to me,” Wright said. “People are saying that we have Black cops, so it’s fine, but even Black cops have bias. Even I have bias, and [the police] being Black doesn’t change the system around us.”

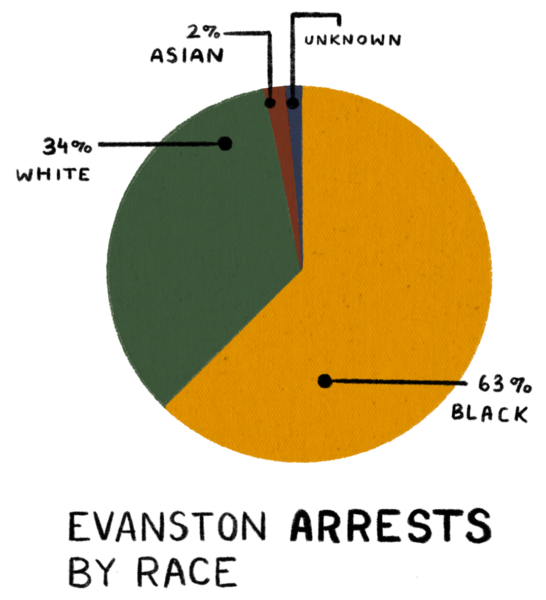

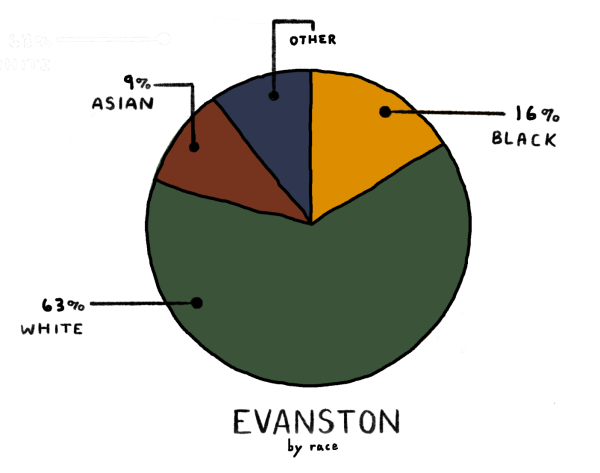

Wright’s experience is backed up by a plethora of disparities demonstrated in the City of Evanston’s self-reported data, which was collected and published publicly up until 2021. According to this data, between 2016 and 2021, Black individuals made up 63 percent of all arrests, while white individuals made up 34 percent of arrests, in a city where only 16 percent of its residents are Black. At the nationwide level, the FBI’s 2019 crime stats find that 26.6 percent of arrests are of Black individuals, while 69.4 percent are by white individuals, with 13.6 percent of the country’s population being Black—meaning the disproportionality in arrests is even more exacerbated in Evanston.

By ward, between 2016 and 2021, the fourth ward has the most arrests at 965 out of 4,250, making up 22.71 percent of total arrests, while the sixth ward has the least arrests at 86 out of 4,250, making up 2.02 percent of total arrests. Within the fourth ward, the area that has the largest concentration of police presence in Evanston, a total of 372 arrests took place right at the area by the Davis St. train stop.

In between those two extremes of the sixth and fourth wards, the eighth ward makes up 18.75 percent of arrests, second ward makes up 17.79 percent of arrests, the fifth ward makes up 10.8 percent of arrests, the third ward makes up 9.25 percent of arrests, the ninth ward makes up 8.68 percent of arrests, the first ward makes up 6.31 percent of arrests and the seventh ward makes up 3.69 percent of arrests.

In the eighth ward specifically, Reid believes that this influx of crime can be largely attributed to the community’s proximity to Chicago and the disenfranchisement of its residents.

“I am happy that Chicago is our neighbor. I am happy to be the councilmember that borders Chicago rather than the councilmember that borders Wilmette, so I am very pleased with who my neighbors are. But, certainly, Chicago is a big city, and we are a big little city, and that means that both of us have our complexities,” Reid said. “There have been decades, if not over a century, of harm that has been perpetrated against Chicago communities that has led them to be disenfranchised. And when you have disenfranchised communities, that leads to an uptick in desperation, which leads to higher rates of crime. So, certainly, bordering Chicago, we’ve had our incidents that have occurred here in Evanston as a result, but I think we’ve had a good partnership between the Evanston Police Department and the 24th district, which is the district that represents the north side of [Chicago] that borders without incident.”

Fast forward to present-day, largely in an effort to curb the disparity of arrests by race, the city continues to roll out new initiatives that work to change the culture of policing.

At the Human Services Committee meeting on Aug. 17, 2022, several council members introduced the possibility of a community responders model that would divert lower-level 911 calls to non-law enforcement for the first time. Overseen by the Law Enforcement Action Partnership (LEAP), these calls include barking dog complaints, verbal disputes between neighbors and individuals with mental and behavioral health, panhandling, vagrancy and other non-violent concerns. However, the model wouldn’t require a new hotline; residents would still dial 911, but the person on the other line would be responsible for transferring the call to the appropriate responder.

Dr. Lionel King, a program specialist for LEAP who conducts qualitative research with 911 calls and manages the recommendation for the Evanston community responders model, explains how LEAP analyzes the narrative of these calls differently from a typical system.

“An incident happens, someone picks up the phone, calls 911 and they receive a call taker on the other line. That person takes notes and gets context of what the call is about. From those notes, the calls are then categorized into what we call call types. So, the person takes notes, and maybe it’s ‘I hear my neighbors arguing. It’s loud, and it seems to be escalating’. So, that call may be categorized as a verbal domestic altercation,” King said. “So what LEAP does, instead of just looking at the call type and saying, ‘Oh, these calls would most likely be community responder eligible,’ we actually look at the call narrative, the notes that were taken, because, from those, you get a lot of clues and context.”

As people with backgrounds in social work, the community responders model does not eradicate the need for police presence in Evanston. Rather, it creates a partnership in which both groups respond to the calls in which they have individually received intensive, specialized training.

“If someone is sleeping in a parking lot, there may be a loitering crime that they have committed, but are the police the best response for that person?” King said. “Would that person not benefit from someone who has expertise in case management, who will be able to connect that person with the type of housing services, mental health or substance abuse services that will be beneficial to them? So, it’s not about right or wrong, but the most appropriate responder.”

While police have historical precedent in being the group responsible for varying levels of calls involving safety, whether mental health related or not, King argues that, under this model, all safety professionals will be regulated to their area of expertise—for police, it’s any form of violence, while for community responders, it’s primarily crisis intervention.

“Police are definitely the appropriate responders when someone has a weapon, has committed an act of violence or has been physically harmed. But, for example, police are not the best responders when there’s a fire, because we need someone with the expertise to put out a fire; police are not the best responders when an individual has gone into cardiac arrest, so we need EMTS,” King said. “Police may not be best as community responders that are trained in mediation, training and conflict resolution and de-escalation in order to resolve that call.”

The community responders model is not a one-size-fits-all solution. For the upcoming months, King, alongside other experts, will continue to research the 911 call narratives to make a tailored recommendation to the city.

“Right now, we’re looking at what sort of training the responders will go through. So, to name a few, conflict resolution, de-escalation, mental health, behavioral health, substance use, first aid and restorative justice practices,” King said. “It’s a variety of training, but it’s also the training of how does this person arrive on a scene without putting themselves in danger. Also, training on the 911 Dispatch protocol, so that they can know how to call for backup in case a situation becomes more unsafe.”

To Reid, who is on the Reimaging Public Safety committee and an active part of the development of this model, by having non-law enforcement in charge of non-violent calls, the city is stepping that much closer to a reformed policing system.

“We have to realize that there has been a flaw in policing since its inception, so I think this community responders model is important for all communities,” Reid said. “I just see Evanston as, because we are a progressive, forward thinking, equitably minded community, it makes sense that we would be one of the first communities to adopt this.”

King, who has seen this model in action in communities across the country, is confident that the model could help curb some of the imbalances in arrest data.

“Evanston has a large minority population. We definitely look at the responder model as a racial justice issue, due to the amount of interactions with the police department between Black and brown residents,” King said. “It gives people the opportunity who may be afraid to call the police, to get that public safety response, so that’s the perfect demographic benefit.”

When developing what the model will look like in Evanston, both LEAP and city officials are examining the ways in which it has already been a success in similar communities. Eugene, Oregon’s CAHOOTS program has diverted behavioral health calls to medical and crisis intervention professionals since its inception in 1989—taking roughly one fifth of the total 911 calls away from the police department.

Mayor Daniel Biss feels that learning from other communities is one of the most important things a city can do when it comes to revitalizing its safety response.

“We love learning from other communities. I think that [safety] issues are really constantly evolving, and there’s always a lot of opportunity for improvement, and therefore a lot that we can benefit from learning from our peers,” Biss said.

In Eugene, the safety of the community responders has rarely been in question; only 0.02 percent of cases have required them to call for back-up from the police department. However, in those few instances where a community responder is unsuccessful in deescalating a situation that turns violent, an officer is no more than a radio call away from stepping in.

“They’re looped in with police dispatch radio, so now they have the ability to call for backup as well as they actually have the notes from the calls narrative,” King said.

This research and recommendation process also includes input from the police department.

“The police department must be involved as a partner in public safety,” King said. “My idea of community responders may not be the same idea of the four branches of the public safety response, which is fire, EMTs, police and community responders working together in conjunction to supply the best and most appropriate public safety response for the citizens of Evanston and eventually the citizens of the United States.”

Stewart feels similarly; the police department is supportive of the initiative, no matter whose jurisdiction it falls under.

“The EPD will be involved in being supportive of however the community responders model turns out. I think successfully as a city, we can’t do this as individual departments. I’m going to be supportive of however that is. I do believe that some sort of community response program can assist the city; we have a lot of people that may need resources and may need help that’s not going to be punitive in nature or criminal in nature,” Stewart said. “And so, I work with my city manager, I work with the mayor, to ensure that I support whatever program we come up with best fits the needs of the city. And in the end, that’s all that matters to me—what’s best for this city. If I’m not involved, or involved from a distance, I’ll still be supportive if it’s what’s best for the community I love that I’m a part of.”

Due to the cutback in calls that police are responsible for, Eugene has saved approximately $8.5 million per year in taxpayer dollars that would have otherwise funded the city’s police presence. While the proposed model in Evanston is still in the early stages of being researching and seeing a tailored recommendation made, Reid believes that a portion of the funding for the program will have to come out of EPD’s annual budget.

“Chief Stewart plays her role, which is to advocate both for public safety but also for the men and women who are in her department, and so Chief Stewart has certainly had some pushback to diverting resources away from the police department,” Reid said. “So, for example, we’ve had about 20 vacancies for some time now, and there are discussions about potentially leaving either all or a portion of those positions vacant and diverting those resources to the new community responder model, and Chief Stewart has shared opposition to that.”

This wouldn’t necessarily mean that the amount of funding diverted to the community responders model would be proportional to the amount of calls taken away from law enforcement’s jurisdiction.

“I personally believe that at least a portion of the police department’s budget will have to go to supporting the community responder model. We can’t remove a significant percentage of the calls that the police department would respond to from their department and not reallocate at least a portion of the resources,” Reid said. “I don’t think it has to be one for one; if we divert 40 percent of their calls away, we don’t need to take 40 percent of the budget. I don’t think that is the case one bit.”

Stewart feels otherwise; in her mind, leaving positions open would harm the community.

“We serve a community. We have nearly 80,000 residents here in this community. We have a number of individuals that come through and come into this community every day. So, I am trying to fill all my vacancies so we can deliver the best service possible to this community. I have not had a conversation with any councilmember, but my stance as the chief of this organization is to fill my vacancies and provide the best service to this community possible,” Stewart said.

By decreasing the number of positions open to law enforcement, Stewart has concerns about the morale and retention of officers.

“I think we’ve been doing pretty good with our recruitment and retention. It’s important in retention to hold on to people that have worked here and make them want to work here and want to be in a very positive environment. And that goes to the morale again, where they don’t fear that individuals will speak about vacancies being taken away from officers. That’s not something I want my officers to think has happened. We have officers that have been working for a very long time short staffed and have still undoubtedly provided unbelievable services to this community,” Stewart said. “I just did the state of the Evanston Police Department, in which I was able to speak upon our impact in fighting crime, the impact on gun violence that we’ve made over the time of my tenure, and how many firearms we’ve been able to take off the street, so we are doing a very good job proactively trying to provide a service and that’s from just having good people, even a mere short staff that want to do that.”

On Aug. 26, 2023, the City of Evanston hosted a gun buyback event in which about 70 firearms were recovered by the police department. For each gun turned in, residents were given $100, with $25 offered for BB and ammunition guns.

“I think the worst thing you can ever do is think that safety is unimportant. One thing I do as the Chief of Police is ensure that that’s a conversation we’ll never want to have with someone’s loved one or a victim of crime,” Stewart said. “It’s important for me as a chief, but it’s also important for me, who’s been impacted by violent crime and lost loved ones to it. So, I just don’t blatantly throw out it’s not important to have staffing. I think it’s extremely important to justify this with the residents and the individuals of this community that really want the police and want more police to keep them safe.”

While city officials and the police department are still in discussion of what the community responders model will look like and where the funding will come from, presentations have been held at ward meetings to communicate its purpose to community members.

“At one of our ward meetings, we had a new staff member who is working on the reimagining portion, and she shared information, and the community members seem to be very much on board with having a community responder program,” Ninth Ward Council Member Juan Geracaris said. “They agreed there are certain calls that don’t need an armed police officer responding to them.”

Sticking with this theme of relationship-building and outreach, another important aspect of the community responders model is the responders’ engagement and regular interaction with Evanston residents.

“What’s important about community responders doing this is that when they hear John Doe, who’s called in every week because he refuses to take his medicine, they know how to engage, and they know how to deal with that,” King said. “They understand how to de-escalate him, because they have gotten to know him. Furthermore, when he has a relationship with the community responders, more information can be had to help.”

This precise model, in which the responders are active members of the community, fits Reid’s view of an ideal public safety response.

“If we had community responders who were out and visible on the streets, talking to neighbors, engaging with community members, maybe even going door-to-door knocking on doors and introducing themselves to folks, that would be the ideal public safety regime—a true community policing model,” Reid said. “Certainly, there’s a place for armed law enforcement, but I think that place, more and more, needs to be diminished. We need folks who are actually out getting to know people in the community, knocking on doors, talking to people, getting the necessary intel.”

When Stewart first entered office, one of her top priorities was to have her law enforcement engage with the community in the same way that Reid described. A year later, Stewart feels that she has largely succeeded in said priority.

“It’s been officers showing up at events, being positive, having those positive engagements and just showing a mutual respect for each other. I made that a focus, too,” Stewart said. “I work a lot of hours on purpose, because there are a lot of events going on—from a block party to a street naming, to maybe an event at the foster senior club. It’s important to be present, and I’ve been told by a number of people in the community and students that they appreciate our officers being present.”

Similarly, Biss finds that this level of interaction is important in reframing how people view law enforcement.

“I think that bad relations with police are an inevitable outcome of you’ve only ever interacted with the police in a negative context. And I’m not saying if you want to ask the police when they are doing something wrong, I’m just saying, if you’re only ever interacting with them when they’re there to discipline, correct, punish, it’s not going to feel very good,” Biss said. “And so I see the police department also moving in this direction and just being present in the community being positive, seeking opportunities for positive interaction. And that doesn’t change the fact that there will be the need for some negative interaction. That’s inherent to the role. But that shouldn’t be the only or even the primary context for police resident interactions.”

Officers can be found at the First Fridays, school block parties, resource fairs and other city-wide events. Because they’re still on duty, many of the officers have the dual responsibility both to keep the event safe and create a partnership between the community and department.

“For law enforcement to just truly understand what’s going on in the community, you have to know the community,” Reid said. “You have to know who the actors are in that community, but, also, it’s to build trust between government and the folks that the government is here to serve. And we know law enforcement is one of the most well financed portions of local government and, maybe sometimes one of the only points of contact that folks have with a local government official. “

After a homicide took the life of someone in the area surrounding her neighborhood, junior Delone Anyang recalls experiencing that sense of community from law enforcement first hand.

“The police were just knocking on all the doors, just asking people how they were doing and if they knew anything,” Anyang said. “It was actually, surprisingly, a very positive and welcoming experience. [The officers] greeted us nicely; they didn’t enter without permission or anything. I left feeling good about it.”

Not all students share the same sentiment as Anyang. To Wright, the prominence of police in the community feels like an attempt to “trick people into thinking they aren’t that bad.”

“Sometimes, I’ll be at those days in the park where they have free food and play basketball, and the police are there. Even if it’s just like them saying, ‘Are you staying out of trouble?’ they wouldn’t say that to a white boy,” Wright said. “Police see us for our skin, and no matter how many football games they go to, it won’t change that. It’ll just make me not want to go either.”

Washington agrees with Wright; it’s difficult to discern between the officer and the human behind the badge.

“Having them be there feels weird to me because, yeah, they might be nice to you now and chatting you up now, but when they’re on duty, it’s a full 180,” Washington said. “Their job is to look for threats, and Black people are targeted and predisposed as being a threat.”

Outside of a relationship with the community, the police department also cultivates a relationship with the city staff.

“It is important, and one of my expectations by the city manager before taking the job was to work jointly with all and any relationships that weren’t strong and make them strong. When I got to the office, I heard that the police department didn’t have a really strong relationship with the schools, so I made it a focus of mine. That’s why you see me; that’s why I’m always around, because I want to ensure that we continue a positive relationship,” Stewart said.

Geracaris recalls that the communication between the city and police has allowed him to become aware of the level of effort that Stewart and the department puts into keeping the community safe.

“I would say [the city council and the police department] have a good working relationship. I came into this as a private citizen. There is a lot more as a city council member that I’m aware of going on in the police department. One of the things that I think is sometimes hard when you’re on council is when there’s a victim or there’s an ongoing threat, we find out from our police department and the city manager almost immediately. We need to know those things,” Geracaris said. “We’re briefed daily on what would be major incidents, so, for me, there’s been a heightened awareness of what’s going on and happening there. I found that Chief Stewart has been really responsive when there is a public safety concern. Just in the last couple of days, we’ve had the bomb threats at the public libraries, which is really concerning, but they’ve been very quick to let us know what’s going on and help the city staff navigate those things.”

Ultimately, the EPD is working to balance cultivating a restorative, equitable space, while still focusing on promoting public safety.

“There are times where we have to make arrests; not every youthful indiscretion can be handled through restorative justice, but whenever possible, we don’t want youthful errors and judgment to be something that somebody’s got to grapple with for a long period of time. So, restorative justice is a priority for our people, for the city, for the department and for the community at large,” Glew said. “That’s been evidenced by the way society has also gone, where expungements of records, especially juvenile records, have become almost automatic. When I first started law enforcement, the age to be charged as an adult was 17, and now it’s 18. So that’s the direction that society has gone, and we filed suit. As a department, we have a very good sense of where our efforts fall into providing safety and guidance for our school and community.”

While city officials, the police department and community members were having conversations about what police reform could look like at the city-wide level in 2020, ETHS administrators were having similar conversations for the school district.

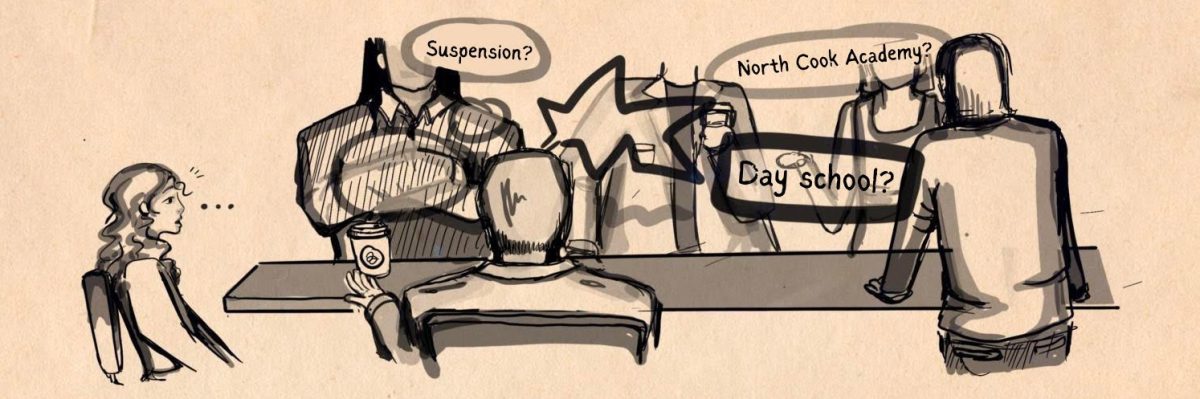

“If I reflect back three years ago, and it was obviously during COVID-19, we were heavily engaged as a discipline committee in reflecting on what our current practices are—understanding, and even sending out surveys to students to families to staff, really digging deep on the ‘let’s understand, what is our position about how our students experience the community,’ but also the conversation about SROs had come up right as a component of that significantly,” Associate Superintendent and Principal Dr. Taya Kinzie, who was the school’s Assistant Principal of Student Services at the time, said earlier this school year. “So, we spent a lot of time really considering who we were asking, and who we were inviting to the table. How can we do that better? Making sure that we’re inviting our transition house into the conversation, our day school into the conversation, all of our off campus students and making sure we’re including everybody in that perspective taking.”

At the time, Superintendent Dr. Marcus Campbell was ETHS’ principal and working alongside Kinzie to have these conversations and explore whether there was still a need for SROs at ETHS.

“The first thing that comes up is, of course, about SROs. So, there’s been a sequence of things that have happened at the national discourse; George Floyd and Breonna Taylor—they get murdered by police, and we begin to talk about policing reforms and should police be in schools, all of the conversations that we should be having,” Campbell said during an Evanstonian interview in the 2023-24 school year. “So back then as principal, I was having conversations with current students, alumni who are reaching out.”

When SROs were first introduced into the building in 1968, ETHS was in the one percent of schools that reported their presence on campus. From Campbell’s perspective, somewhere in the 90s, the SRO partnership shifted from being an integral part of a community policing philosophy to a system defined by surveillance—a status he worked to change throughout his tenure.

“Somewhere in the 90s, it became more about surveillance and policing and zero tolerance than it did about partnering,” Campbell said. “So, over the years since I’ve been here, SROs have not been a part of any kind of surveillance structure. At some schools, they give detentions, some schools they monitor the halls, and we have very explicit criteria. If you get the SROs involved, you pretty much take it out of the schools hands; the SROs don’t break up fights and stuff like that, because you’re calling the police.”

Although the main role of SROs is to protect the school from external threats, prompting them to always be on alert and in communication with the EPD, SRO Officer Willie Hunt explains that another important aspect of their position is bridging a gap between the school district and police department.

“Being an SRO starts with bridging a gap between the police and ETHS, whereas we’re seen in the building, and we’re not just seen in the building when there’s a problem. So, it shows consistency with us being around students, and it allows us to build relationships so we can be those mentors for the students in a building,” Hunt said. “On top of that, we will also be first responders. ETHS is a very big school, so without having officers in the building It’ll be difficult if there was an emergency or a police officer off the street coming in and navigating the school.”

By being in constant communication with the police department, this bridge also allows Stewart to be aware of any safety concerns both in the school and broader community.

“I’m never more than a phone call away. I might normally see one of the SROs before they go to the high school, and once or twice a week, they stop in the office, and we keep each other aware of anything that’s going on nationally or anything that could affect the high school or students related to safety,” Stewart said.

In order to maintain a relationship with the school, the SROs are constantly making an effort to get to know the students. At almost every school event—football games, block parties or dances—both officers are seen in the crowds, talking to students and acting as community liaisons.

“We have conversations with them that don’t involve us interviewing them about something that happened; we’re laughing and joking with them, talking sports with them,” Hunt said.

In her role, SRO Officer Grace Carmicheal wants to build relationships with kids and offer support or guidance.

“[Hunt and I] are authority figures—we’re different adults that can actually listen to what a kid has to say instead of just going, ‘Oh, you didn’t do it, right?’ That’s helpful,” Carmicheal said. “For me, that’s just my personality—I’m a professional auntie.”

For Campbell, the relationships described by Carmichael are often part of the reason he sees officers taking on the role of SRO.

“I believe that what the SROs get from working with [ETHS], I think for some of the ones that I’ve worked with, it’s why they went into policing—they get to work with youth to prevent them from being a part of the criminal justice system,” Campbell said.

However, no matter how much time the SROs dedicate to building relationships and connecting with students, many students of color still attest to their presence contributing to a negative learning environment.

“[The SROs} make me feel uncomfortable because we understand they need to keep the school safe, at any means necessary. I’m never going to hold you for that, but I’m still afraid that if something goes wrong, how would they handle it? If a student is stimming, would they think it is a threat? How would they handle that as police, and they’re trained the way they are trained?” Burnett said. “I think of all the different circumstances that could have happened for the police to end up being in our school and doing exactly what the police have done to minorities. The school is filled with minorities, so it seems a little tone deaf to have police officers in a school full of minorities when you know that the school-to-prison pipeline is so prevalent. It’s doing nothing but scare tactics.”

For Wright, SROs serve as a reminder of police brutality during the school day, a time when he expects to be protected and safe.

“I don’t know who in their right mind thinks it makes sense to have cops in schools,” Wright said. “What’s the point? We already have safety staff. I looked at them in the hallways while I was at school, a place I went to for learning, and it was like I saw George Floyd, and I saw Breonna Taylor, and I saw Jacob Blake, and I saw what could be me if I run into a cop on a bad day, and it was like, ‘I’m at school. Can I get a break from being a target for once in my life? Why are you here?’”

While Campbell understands the impact that having SROs can have on a student’s wellbeing, for him, it’s about creating a balance between ensuring safety and supporting those students.

“We certainly know that Black and brown students can be negatively impacted by the presence of police in a learning environment,” Campbell said. “That’s the conversation for us. And how do we balance that out, along with the potential when you have 5,000 people in a building every day? How do you balance the public safety element to that?”

One way in which Campbell and the EPD has worked to make the SRO presence less triggering for students is through their uniforms. In the past, the SROs would be at the school in a typical police uniform, with a bulletproof vest on, but, now, SROs can be seen around the school wearing a simple ETHS t-shirt.

“We’re going to [move SROs] away from uniforms that may be what we stick with forever,” Glew said. “There may be things that change that we have to do. Right now, it’s a softer appearance, not having that more authoritative uniform.”

Glew also feels that by having SROs in the building, students are less likely to view police in a negative light.

“I’m not an SRO, but I would say an important part of the SRO is kind of pivoting back to in the wake of George Floyd and some of the negative outlook on law enforcement,” Glew said. “Having the SROs in the schools and having that relationship building is important. I think in the wake of those societal changes that have a large impact on people, especially people that are younger. If you are in seventh, eighth grade and all you’re seeing for a whole summer, a year and a half, is a lot of negative [police coverage] whether it be warranted or not.”

In 2019, District 65 got rid of their SROs, and since then, no more arrests were made on campus—prompting many to believe that their presence contributes to arrests being made in situations that don’t warrant police. For Reid, D65’s removal of SROs raises concerns about the effectiveness of their role in the first place.

“You look at particular numbers for arrests and other interactions with law enforcement that could have been avoided and could have potentially been better handled by the district and by parents,” Reid said. “I think it makes sense that we don’t need law enforcement officers standing inside of our schools, particularly in our elementary schools and our high schools.”

But for class of 2024 dean Nichole Boyd, SROs serve as a vital support to the ETHS safety staff and dean’s office—especially during incidents involving guns and other weapons found on campus.

“Some of my colleagues have had to deal with students with [guns]. I have not, thank goodness, but knowing that [the SROs] are down the hall is a relief, because I will be a little freaked out,” Boyd said. “So, just the reassurance that they have relationships with kids, kids come talk to them about the things that happened in the community over the weekends, if there’s a situation that is escalating, or when it becomes a police matter and then the school has to back off.”

As one of the largest high schools in the country, ETHS safety staff—deans, SROs and safety officers—are constantly in communication with one another to ensure that all concerns are being approached effectively. This translates to weekly meetings with the entire staff and morning check-ins with the SROs.

“We share information. We have to have each other’s back. The [safety staff] are boots on the ground; they’re right in the forefront. They hear the rumblings in the cafeteria, they see the stuff pop off in the hallway. So, we’re always supporting one another,” Boyd said. “There’s 5,000 people in this building, and I know we’re talking about discipline, but we also have a responsibility to keep everybody safe. As deans, we can’t do that; we have 1,000 kids in each of our classes, so with the safety staff and the SROs, we have to be a team.”

For the majority of safety concerns—fights in the hallways, drug usage, verbal disputes and other matters that don’t pose a threat to the security of the building—the safety officers are ETHS’ primary responders.

“Safety handles 97 percent of the things that go on, from kids having outbursts in class and we go talk to the dean to any number of things,” Carmichael said. “If there’s something where crime has been committed or is being committed, and it’s something that the school wants the police to handle, we have those things.”

The safety officers, positioned throughout the day at every entrance and spots around the school, are there to ensure that students, staff, and visitors are where they need to be and are supported in the case of an incident or emergency.

A large portion of the safety staff at ETHS were students here themselves—providing them with a unique perspective of the student experience.

“Back in the day, I used to be one of those rowdy kids; I used to be a little louder,” safety officer Anthony Jones said. “So, I used to get in trouble and visit Dean Soriano often, but I did have someone show me a path of good and bad habits, and I was definitely on a wrong path when I was younger, but I did get it together. That’s what I’m trying to do; I’m trying to show to kids that you can get better.”

Despite the connection that many students have with safety, some see them as an extra level of surveillance. For Washington, while she has not had poor experiences with safety staff, she has seen her peers targeted in the past.

“Coming into lunch, and leaving the school, I haven’t really had any negative experiences particularly, but I do notice safeties, especially with monitoring students in the hallways, they do target certain groups of students like me,” Washington said. “I am a person of color who exists at ETHS; in particular, I’m not targeted, but there are people who are targeted. Like when safeties will stop them in the hallway for not having a pass or like being in the hallway for literally 30 seconds longer than the bell.”

Safety Carnell Ingrim, known by students as ‘Unc,’ feels that students often perceive him and his colleagues as threats.

“They see these orange shirts, and they think we’re a threat, and half the time, all you do is talk to us, and you’ll find we’re some of the coolest people you know. It’s not the majority of students, but it’s enough that we can feel the animosity from certain students, for whatever reason,” Ingrim said. “But I think the relationship between the safety and the students is good, it could be better than what it is. It’s not to my satisfaction, but I’m just one person.”

To work toward a better relationship between students and safety staff, Ingrim makes an effort to level with students and see scenarios from their perspective.

“I try to talk to you, not at you. I try to talk to you and try to show you a different way. I’m also the type of person to play devil’s advocate with students. When I see you do a certain thing, I give you a scenario, good and bad. So, I play the devil’s advocate to show you the error you made or what you could have done differently,” Ingrim said. “When I approach the students like that, that actually works out a lot because a lot of times we, the adults in this building forget we were teenagers too. We forget we used to be you, and sometimes, you all forget we used to be you.”

On Dec. 16, 2021, ETHS was put on hard lockdown after two loaded guns were found in the backpacks of two students. Following the lockdown, community and school conversations were amplified, and questions were raised about how safe school really is for ETHS students.

Hunt, who has been through an extensive amount of city and active shooter training, explains how every incident—whether the lockdown at ETHS or a shooting in another state—is a learning experience for the police department.

“It is always a learning experience because everything is not going to go ABCDEFG, so things may start off with E and we have to go back to D. So, when we deal with a situation like this, our commander sets up a debriefing, and we have those conversations of how we can do better. It’s not that we did anything wrong at that point, but it’s always improving,” Hunt said. “Since the first shooting, we’ve had all these other situations and every situation we have, even with what just happened in Uvalde, and other active shooter situations; it is always a learning experience.”

While the school is primarily looking at the lockdown to figure out ways to make the school physically safer, Reid argues that the conversation should examine not only how to prevent students from bringing weapons to school, but also finding the underlying cause of why students feel unsafe enough to bring these weapons, and how the school and city can partner to better support them.

“I think it’s an unfortunate reality that there are folks who come from certain socio-economic backgrounds and cultural backgrounds where gun ownership is prevalent, and illegal gun ownership is prevalent and folks feel as though they need to carry a firearm to protect themselves,” Reid said. “And that is not the world I want to live in, but unfortunately, it is the world that we live in. And so I think those situations require intervention in a way that is thoughtful and considerate to folks whose background is the reason that they might carry a firearm. I think we can deal with that, particularly for high school students who are doing this. I think even more of that could be diverted outside of the traditional criminal justice system, and more into a restorative justice system.”

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, Evanston saw a dramatic increase in youth gun violence. ETHS students lost friends, family and neighbors as this violence touched every corner of the community—The McDonald’s on Dempster, Clark Street Beach, the Mobil Gas Station off of Green Bay Road—places that were once for casual gatherings morphed into dark reminders of those lost. Wright was one of the many who lost a close friend through a recent act of gun violence.

“I think [the shooting] was in some ways a wake up call,” Wright said. “I don’t know if that’s the right word, but it was the worst thing I’ve gone through–and it was worse for the people there and his family, but, god damn, he was a brother.”

Reid, councilmember since 2021, recognizes the connection between the uptick in gun violence and the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Youth gun violence over the last few years has seemingly increased in Evanston, in part, because when there’s an economic downturn, people get more desperate, people are in more need,” Reid said. “I think this is a direct response to the pandemic and the economic hardships that the pandemic cost—plus, you lay on top of [the pandemic] mental health issues that were caused by the separation that occurred during the pandemic.”

In recent incidents of youth gun violence, all victims were young Black men and boys—a demographic already disproportionately impacted by police and gun violence, in parallel with the disparities represented through the City of Evanston arrest data.

“Many of the kids that we’ve buried in this town have been Black boys in special education,” Campbell said. “Over my life, I’ve seen kids die. I’ve seen kids get locked up. And these were my friends; these weren’t ‘bad’ kids. I see myself through all of this. I remember as a kid growing up wanting to be a teacher because I wanted to save the lives of my friends. That’s why I’ve got an education.”

Now, Campbell signs his name at the end of mass D202 emails with the subject line “Sad News: A Time for Support,” when another student is lost to community violence. “I’ve been here for 20 years; I’ve said it as a superintendent: we have to do better.”

Within Evanston, there are groups aiming to do better—to not only lessen disparity, but to prevent violence as a whole. The My City, Your City, Our City (MCYCOC) initiative works to strengthen community bonds—through informative resources, engaging programming and access to a network of support, the initiative aims to prevent youth gun violence across Evanston.

Jeremy McCray, the City of Evanston’s Youth and Family Services Director, helped to organize the MCYCOC ‘First Friday’ event, which has taken place annually each summer since the pandemic.

“This was brought to us by past shootings in Evanston that took some lives and set us back,” McCray said. “And we wanted to see how much we can help the City of Evanston as a department, bring something back to the community where people can come in, enjoy a safe space and just have a good time. So, with that, we asked the community what they would like to see; they wanted to see more block parties, family events, people being together, people enjoying each other’s company. So, we came up with the First Friday idea.”

MCYCOC is a part of The Collective—a group of local youth-serving organizations, including the James B. Moran Center for Youth Advocacy, which provides “community-based legal, mental health, and restorative services for youth and families.”

Pamela Cytrynbaum, a Restorative Justice Coordinator at the Moran Center, emphasizes the connection between youth and the mission of the center.

“Our attorneys are working very hard to support and defend and get the needs met for young people who are profoundly marginalized and isolated,” Cytrynbaum said. “And our restorative processes—all of us are working deeply with our community partners, and [youth].

Exposure to violence can affect every aspect of a student’s experience, both on and off the ETHS campus. Students carry their experiences with them, and the school day may be difficult for those experiencing violence and trauma outside of the building. When an incident of gun violence occurs in the community, District 202 works to make connections with those involved and determine student needs from there. Following the Clark Street Beach shooting in April of 2023, meetings were held between school and city officials in order to make a plan to best support those students involved.

“There are all of these mental health supports, support groups and the deans who really get involved to to support kids who’ve been impacted,” Campbell said. “Either they knew someone that was killed or shot, shot at, that whole continuum, and we have very, very intense support for the kids. And since these [incidents] have occurred in the last year, we’ve gotten the city involved. So now, and I’ve been calling these meetings where it’s been ETHS, District 65 and the City of Evanston and [sometimes] the Chief of Police, the [D65] superintendent, city manager, the director of Parks and Rec—we have all been in the office at the same time talking about, ‘Hey, listen, we need to be coordinating our efforts together.’ Because what happens at Clark Street Beach has an impact on all of us sitting here.”

After Burnett witnessed the Clark Street Beach shooting from just a few feet away, a friend referred her to the ETHS social work office.

“The social worker was great,” Burnett said. “I talked it through, and they gave me clarity that I wasn’t going to have to talk to the police unless I wanted to talk to the police.”

Recently, the Handle with Care model has been discussed for possible implementation at ETHS in conjunction with the preexisting SRO program. In practice, the model involves a law enforcement officer at the scene of a violent incident (whether that be firearm-related, abuse, neglect or physical altercation) identifying that a child has been affected by this trauma. The child’s identifying information is then sent to their school, along with a three word message reading “Handle with Care,” with the intent of informing the school of the child’s recent exposure to a traumatic event.

“It’s very regulated,” Glew said. “But that model seeks to release what information can be released proactively just to alert school officials and administrators that something has happened in this kid’s life. They can’t necessarily share what it is, but in essence, handle the student with care.”

Along with the possibility of adopting Handle With Care, ETHS practices the Acknowledge, Care, Tell model. This model includes three steps outlined on the D202 website, as well as on other school communications.

“Acknowlegde, Care, Tell is a statement that came from prevention, both for homicide and suicide, and that’s how we apply it, so we’re all looking out for each other,” Kinzie said. “What we’ve seen—especially when students are having their own experiences and have knowledge of violence—is that it’s critical that families continue to reach out, and they do. Sometimes, they reach out to us and not even the police.”

For Boyd, as senior dean at ETHS, the model can help to diffuse the conflicts brought to her office before the situation escalates.

“We are really big on Acknowledge, Care, Tell,” Boyd said. “When students share information with us, we can get ahead of things. Sometimes, people are just triggered when they see someone, and it’s just happening in the hallway. Other times, students come to talk to us first if they’re about to get in a conflict…so to the extent that we can, we do want to meet with students to be able to get ahead of [conflict], like in situations of bullying or fighting. Students are really good about coming to talk to us and their desire to be anonymous, and we honor that.”

Both the SRO program and Acknowledge, Care, Tell model are based upon building connections between the school and community and are a working effort to bridge safety on and off campus. For these concepts to work most effectively, students must have trusting relationships with ETHS staff and administrators—as well as with law enforcement. Problems may arise, however, when that trust is brought into question.

Preparing to walk through the bag check at an ETHS football game last September, then-junior Jamie Davis*, a woman of color, began unzipping the smallest pocket in her bag. Often having to take public transportation after school and after games, Davis kept a small pocket knife in her bag—just in case she had to use it for self defense on her way home. Knowing the possession of a knife was clearly against state and school code, Davis was ready to hand it to the safety officer sifting through the line just a few feet away.

“The safety staff asked me if I had any weapons or anything I knew of in my bag,” Davis said. “I was really open and honest. I told her that I had a small pocket knife in the smallest part of my bag–and so she took it out, and she told me I was good to go.”

Davis then joined her friends in the stands to watch the game; she had figured that being honest and surrendering her pocket knife at the gates would ensure she wouldn’t get in trouble, especially considering the reason for her possession of it. But 10 minutes later, she was pulled from the stands by a safety officer and administration staff.

“[The staff members] came and got me from the stands and told me that I needed to leave. I was like, ‘Why do I need to leave?’” Davis said. “They said it was because I was endangering everyone. I understand the [no weapons] policy, but I was confused because I was being really honest about [the pocket knife], and they had already taken it away.”

Davis was then escorted out of Lazier by the police, with what she felt was little explanation or discussion as to why. She was taken across the street, off campus, and told to either go home or stay off campus for the rest of the night. Davis, who didn’t have a ride until around 10 p.m., sat on the curb of Church Street for two hours waiting for her mom to get off of work—despite the fact that she had explained to the officers that she had nowhere safe to go until her mom was available.

“They made a big deal about it,” she said. “It gave me a lot of anxiety. I have really bad anxiety, and it was really overwhelming, so I started crying.”

As Davis sat in the dark waiting to be picked up, she had no idea that this incident would end up shaping the trajectory of her education—recommended for expulsion following the incident, the rest of Davis’ high school career was suddenly at risk. She had brought a weapon on campus, and despite its usage or intent, she would face the consequences outlined in state and school policy.

Through the school’s tiered discipline model, Davis was given three options: she could appeal the recommended expulsion, attend an alternative schooling program on the west side of Chicago or attend North Cook Academy. After a long process of appealing her expulsion with the help of specific ETHS teachers and a Moran Center attorney, Davis ended up spending four months at North Cook during the winter of her junior year.

When bringing her pocket knife onto school grounds, Davis violated the ETHS family and student handbook, the Pilot, which outlines the protocol and policy involved with everything from reporting absences to the possibility of an active shooter on campus. In parallel with state law, the Pilot states that “no weapons, firearms, ammunition, knives of any kind, tasers, or other dangerous instruments or articles of any kind are permitted on school property.” Further, the Student Behavior Code ensures that all ETHS policies are followed while on campus, at activities, and while traveling to and from school.

Currently, the ETHS safety department uses three resources that allow students to report incidents that occur both on and off campus: the ETHS Safety Crisis Line, Text-A-Tip, and a general incident reporting form. Combined with other safety supports such as the Acknowledge, Care, Tell model and the presence of SROs, these reporting tools work to prevent situations from escalating or remaining unknown to the appropriate department.

“The importance of keeping a safe environment is paramount,” Associate Principal of Educational Services Dr. Kieth Robinson said. “Everything is aligned in our policy books. Everything is a step-by-step process, and we follow that.”

Following the December 2021 lockdown, Robinson prioritized communicating these expectations and policies more clearly to students and visitors.

“There used to be this generalized thing of ‘Don’t bring weapons to school,’ but we have now been way more specific about what not to bring and [through that specificity] really try to lift up school policy,” said Robinson.

Along with the emphasis on pre-existing policies following the lockdown, ETHS had the Facility Engineering Association (FEA) produce an in-depth evaluation of safety on campus. As a result of the FEA findings, ETHS made several changes to the way safety procedures operated beginning at the start of the 2022-23 school year. These changes included structural improvements to doors, fences, and windows, new policies on ID scanning, safety officer presence and an improved staff training program.

“Most of what we put into place were things that were on our radar for implementation anyway, but some of which were recommendations from the FEA about scanning and [and other safety practices],” Kinzie said in a past interview with the Evanstonian. “We are taking into consideration those recommendations as we look at moving forward. [The FEA assessment] was a really comprehensive audit of our entire facilities, inside and outside.”

Despite the improvements made to safety policies following the audit and the work done by the ETHS safety department, a significant number of students still report feeling unsafe at school.

Each year, along with many other Illinois public schools, ETHS administers the 5Essentials Survey to students and staff in order to measure five indicators determined to improve student success. Through a series of questions surrounding student perspective both in and out of the building, ETHS is able to determine not only successes, but also disparities within the core ways in which school-wide policy functions.

In the context of a supportive environment at school, the 5Essentials survey defines safety as when students feel safe both in and around the school building, and while they travel to and from home. Within the safety portion of the survey, students were asked to report how safe they feel in certain areas of the school (classroom, bathroom, hallways, etc), and within the areas outside the school. Available answers range from not safe to very unsafe, and responses are then used to determine how well the school is performing on safety based on a score produced from a scale of 0 (very weak) to 100 (very strong.)

In 2022, survey results showed that ETHS fell in the range of 40-60, which is categorized as neutral by 5Essentials. However, when the responses are categorized by race, significant disparities are revealed. On average, the responses collected from Black students at ETHS score at almost 10 points lower than the score produced by responses from white students. This places ETHS’s safety performance score within the “weak” threshold for Black students compared to the “neutral” score across all races.

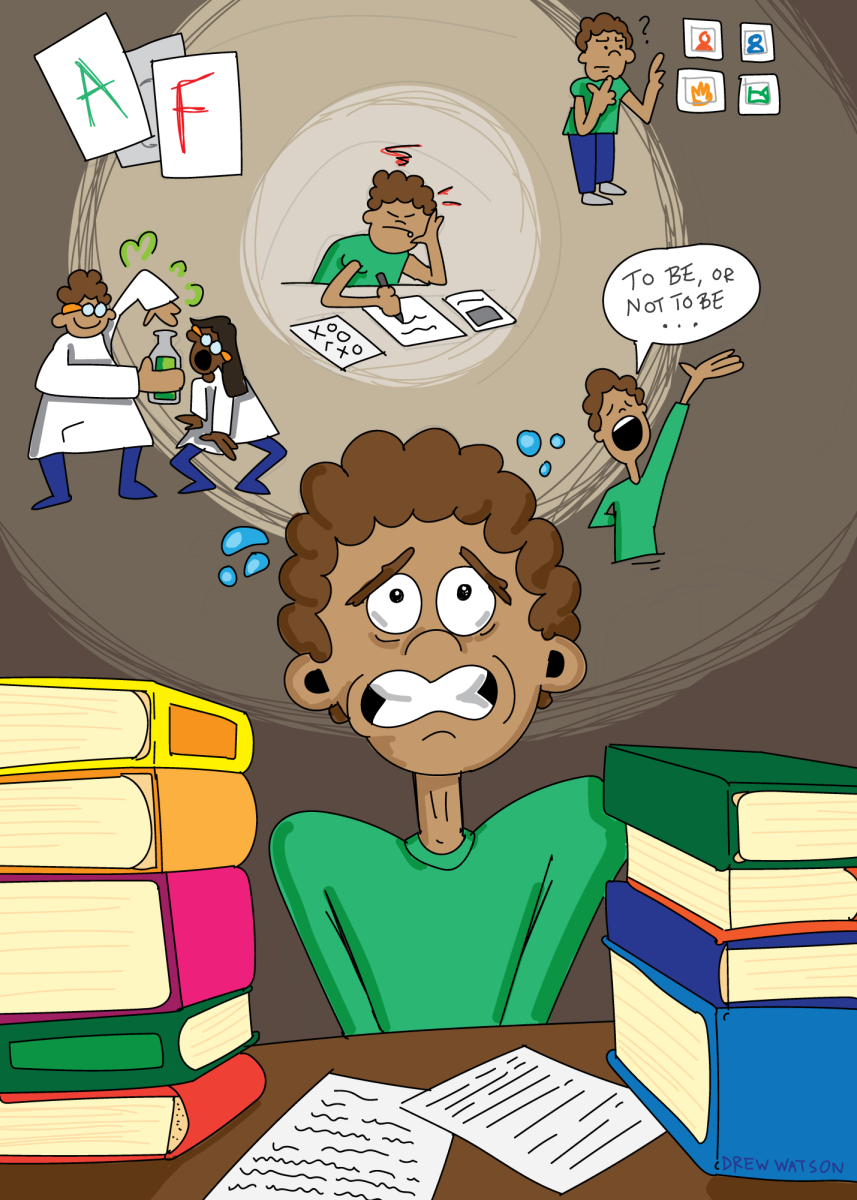

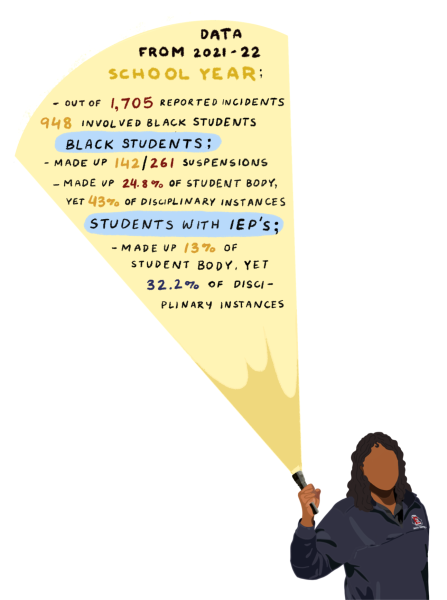

And in addition to Black students being disproportionately disciplined, those with IEPs (Individualized Education Plans) are also heavily affected by disciplinary practices at ETHS. While students with IEPs make up 13 percent of the ETHS population, 32.2 percent of unique disciplinary incidents involved students with IEPs.

When thinking about school safety, Director of Special Education Amy Verbrick identifies a sense of belonging as the most important factor in keeping students safe—and feeling safe.

“Ultimately the biggest factor is—I get emotional about this part—kids need to feel like they belong,” Verbrick said. “And how do we do that? We have to take the time to listen. Everybody deserves to belong. Feeling a sense of belonging at school is a foundation for being ready to learn.”

For students with IEPs who have physical, mental or learning disabilities, the ETHS Day School offers an alternative environment for learning that may feel safer than the traditional campus.

“When decison-making issues, issues of safety, or mental health is a concern, that’s when we consider the Day School,” Verbrick said.

With a core curriculum parallel to that of the traditional ETHS curriculum, students are able to learn in a smaller, individualized environment.

“But we always broach the subject—what at the main building could meet your needs, and [what] do you have readiness for so that you can be with your gen-ed peers, so that you can have access to your school?” Verbrick said. “It’s your school community. So, some students find that safety at the day school and that it’s their school community.”

Beyond offering a safer environment for students whose needs are not met on the main ETHS campus, the Day School also serves as space for students whose behaviors may be disruptive or unsafe in a traditional classroom or school environment.

“The need for discipline comes from behaviors that are disrupting school or preventing school success.,” Verbrick said. “And so we have to look at it from a safety perspective for that individual student and for the school community. So [enrollment at the Day School] wouldn’t be a disciplinary response per se, but it would be a response to meeting a student’s well-being needs in order to be successful in school”

On page 70 of The Pilot, the student behavior code section begins with the district’s discipline philosophy. In alignment with ETHS’ equity and vision statements, the philosophy is guided by the rights of students as individuals, restorative practices, the acknowledgement of an individual’s identities and background and a collaborative effort between students and staff.

For Boyd, the discipline process and her work as a dean is all about relationship building.

“Relationship building is at the heart of my work—getting to know students and understanding their stories and perspectives, trying to teach behaviors and reteach behaviors,” Boyd said. “That’s the hard part. Some students struggle with perspective taking and see things only their way, their side, their opinion; how they grew up, their family values. So trying to get students to understand other people’s agendas, that’s a challenge.”

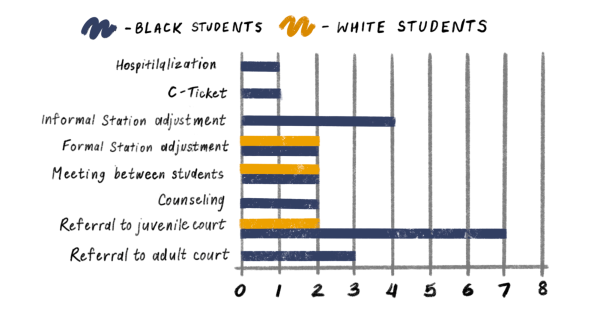

While many staff members work to build those relationships and center equity in the process, the 2021-22 discipline report found that, despite Black students making up 24.8 percent of the ETHS population, 43 percent of students involved in disciplinary incidents were Black. Out of the 1,705 incidents reported during the 2021, 948 of them involved Black students–and with 261 out of 1,705 incidents resulting in student suspension, 142 of the students suspended were also Black. These numbers, for Campbell, aren’t a recent development.

“[These disparities] are an age-old problem at ETHS,” Campbell said. “This is our challenge.”

During the April 17th, 2023 school board meeting, ETHS shared that out of the over 3,000 referrals made to the dean’s office that school year, over 1,700 were escalated into full incident reports.

In response to the rate of escalations and incident reports, school board vice president Monique Parsons expressed concern regarding the connection between this rate and the racial disparities recorded within the discipline report.

“If we see an issue in a classroom with a certain teacher writing referrals where [the deans] don’t escalate it, there’s an issue,” Parsons said during the meeting. “That’s my goal, quite honestly. I don’t want our Black boys being suspended at a record rate, and I get the decline, but it’s still a gap, and they’re still at the top, which means there is still an issue of them not belonging.”

For Wright, the adults in charge of the discipline procedures following several incidents in which he was involved made it difficult for him not only to feel capable of changing his behavior, but to feel a sense of safety and belonging.

“There were some adults in the building where it felt like, from day one, that they knew I was a failure, they knew I wouldn’t amount to anything. So I didn’t amount to anything, and they didn’t expect anything different,” Wright said. “Like, ‘Oh [Wright is] back in the dean’s office again? Same old, same old, because nothing is ever going to change. But the thing is, I could have changed if I had that push, if I had that support. I wish I could redo school all over again and redo those moments and tell myself I can change. There was just this assumption that I was going to fail, and that made me feel pretty damn unsafe and worthless.”

Currently, students who are involved in altercations and violations of The Pilot are given several options moving forward based upon the severity and impact of their actions. For students with multiple suspensions or those pending expulsion, North Cook Academy serves as an alternative schooling option. Instead of attending school at the main ETHS campus, students attend classes and programming at North Cook’s campus in Des Plaines, with the curriculum fulfilling the basic core credits required for graduation.

During the expulsion appeal process following her Pilot violation, Davis attended North Cook Academy.

“It felt like a prison like every morning,” she said. “Every morning, I would have to go in there, and they would have the metal detector scan me, I had to take my shoes off. At the time I phoned in for the whole day and couldn’t get access to the outside. So I was just really isolated, and it just felt really different.”

For Wright, who received many suspensions and incident reports, it felt as though his grade level IEP team was not there to support him through the disciplinary process.

“There was no intervention or whatever,” Wright said.“They didn’t care. I was getting suspended a bunch, and they didn’t care, but they were supposed to be my team. It doesn’t feel like a team when they’re all working against you.”

In order to build these trusting relationships that Wright didn’t feel were available to him and curve the disparities recognized within the data, Verbrick and the Special Education Department work to build individualized plans for each student they work with.

“Each individual’s story teaches us something that we need to know,” said Verbrick. “We can certainly look for patterns, and the patterns then can tell us what we might need to do differently in terms of programming.”

As represented by the data in ETHS’ 2021-22 discipline report and the results of the 2022 5Essentials survey, Black students and those with IEPs are not only disproportionately affected by disciplinary practices—these same students are also the ones who feel the least safe at school.

For Spells, while the primary responsibility of the ETHS safety department is to ensure the physical safety of all individuals on campus, relationship building is a core way to prevent incidents from happening and keep students feeling safe while on campus.

“[Early prevention] is truly relational,” said Spells. “It’s about making certain that every student and staff for that matter feel seen, feel heard, feel connected, feel a great sense of belonging.”

One of the primary ways in which the district is working to curve the racial disparities within discipline and safety is through the implementation of restorative practices—rather than focusing on punitive and traditional methods of discipline, a restorative approach allows those involved to focus on the relationship building and early prevention highlighted by Spells.

As defined by the Moran Center, restorative justice “reflects the reality that acts of wrongdoing do not just violate laws and rules but, more importantly harm people, communities, and relationships…by focusing on repairing harm and addressing root causes, relationships are strengthened, youth have a more meaningful opportunity to grow and learn from their mistakes, and future harm is less likely.”

Through its partnership and conversations with ETHS administrators, the Moran Center is committed to advocating for restorative alternatives to suspension.

“Instead of just suspension or in school suspension, where you’re staring at the wall, what might that restorative experience look like? And again, I would say, let’s look at models of schools that are already doing that, and let’s ask students what would be helpful and let’s have students involved in the creation of those models,” Cytrynbaum said. “We would need a peace room, we would need a place, we would need people trained.”

Once a student returns to the main building from either an out-of-school or in-school suspension, the same stressors that were in place before the student was removed from their learning environment are often still present—often making it difficult for them to readjust to being in school. While ETHS does have a formal re-entry process for students that involves a meeting with their grade-level team, Cytranbaum feels that there also needs to be a restorative process in place.