Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Nashville in November 2025, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

Governmental action on Sand Creek in recent years

Content warning: The following article contains graphic, disturbing descriptions of the aftermath of the Sand Creek Massacre.

February 27, 2023

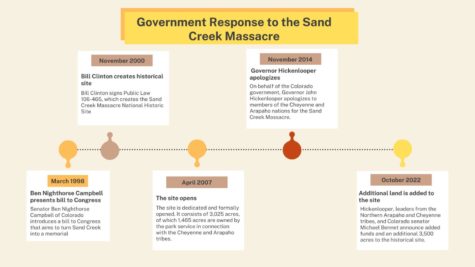

After 149 years of oppression and ignorance from the government, Colorado Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell, the first Native American to ever serve in Congress, created a bill in hopes of preserving the site and Sand Creek. The bill aimed to kindle the memorialization of the site at Sand Creek, protecting the area for the purpose of honoring the many Cheyenne and Arapaho people who were victims of the massacre. Campbell, who is American Cheyenne, was one of Colorado’s representatives of its third congressional district prior to becoming one of the state’s two senators, made the first governmental move toward preserving the historical site, making a statement on March 2, 1998.

Introducing the importance of the Sand Creek Massacre sight, Campbell highlighted the importance of preserving the land as a protected place.

“This bill authorizes the government to preserve such a significant piece of history that I believe is needed to remind us not just of the horrible deeds that took place in this country, but to the native Americans and to honor their memory.”

Campbell then described the atrocious events of the Sand Creek Massacre. Starting with the unsuspecting demeanor of the familiar peace chief, Black Kettle, he described the vulnerable state of the tribes going about their day. With the impending wave of soldiers taking over, Campbell touched on the large difference in scale between soldiers killed from the Colorado militia and the large number of Native Americans brutally murdered. He describes the grotesque forms of torture used on many people and the inhumane actions of such soldiers after the massacre eventually subsided.

“When the skirmish ended, the Colorado volunteers then scalped and sexually mutilated many of the bodies of these people and proudly displayed their trophies to jeering crowds on the streets of Denver while desecrating the Cheyenne heritage,” explained Campbell.

By examining the relentless torture and cultural denigration, Campbell made clear the justice and healing that has yet to become present for many descendants of the Cheyenne and Araphaho tribes. He recounted the lack of reparations or attempts at remembering the tragedies that took place at Sand Creek over the 149 years.

Campbell encouraged the preservation of the site by pointing out the unique opportunity of the government. With the site being sold, there is no better moment to do whatever the government can to obtain the land.

“This action will provide remembrance to the event and allow present and future generations of Americans to learn from our history—including much more glory and grace.”

Sand Creek National Historic Site

In October 1865, the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes signed the Treaty of Little Arkansas, which offered them reparations for the Sand Creek Massacre in addition to access to the lands south of the Arkansas River. Less than two years later, however, the original treaty was essentially scrapped, and the Medicine Lodge Treaty reduced the allocated reservation lands by 90 percent. The promised reparations were never paid or even kept track of by the U.S. government, despite more than a hundred attempts to account for them over the last century.

Efforts to establish a Sand Creek National Historic Site began with the passage of Public Law 105-243, which mandated that the National Park Service determine the exact location of the massacre. Using historical documentation, oral history, aerial photography and archeology, a team of researchers pieced together answers and found the exact locations where the events of the massacre took place. The bill was sponsored by Campbell.

On Nov. 7, 2000, President Bill Clinton signed Public Law 106-465, which created the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. The site was dedicated and formally opened on April 27, 2007. It consists of 3,025 acres, of which about 1,560 acres are owned by the National Park Service and 1,465 acres are owned by the park service in connection with the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. The site, located in southeast Colorado, includes a bookstore, a visitor picnic area and Monument Hill, upon which one can overlook Sand Creek.

“Throughout all of that process, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes were very much involved. Every time they would study at the site, there were tribal representatives here,” Teri Jobe, a park guide at the site, notes. “There were a lot of meetings between National Park Service Representatives, the tribal representatives and also local people from some of the towns nearby like Eve and Lamar.”

Today, through the work of the site, people from all walks of life are educated on the atrocities that occurred at Sand Creek.

“It’s not a conflict that a lot of people know about, and so it’s helpful for people who are even just driving by on the road, they sometimes see the sign and will go, ‘Oh, National Park. Let’s go,’” Jobe says. “Some people have prior knowledge. There has been a movement in Colorado to put this into schools. Some people have studied, and some people have come back many times over the years because they feel a connection to this place. We do not let people go into the site itself where the camp was and where the massacre actually took place because that is considered sacred ground to the tribe today. People can see that site from what we call a monument hill, looking down into the valley and the same Big Sandy Creek, and you can see that area really well from monument hill.”

Another significant change made by the bill was the name of the site itself. Previously, the site had been marked by a red granite headstone, referring to Sand Creek as a battleground. This often skewed public perception in favor of Chivington.

“For about a hundred years, the people living in the territory, and later the state of Colorado, felt that what John Chivington had done, while not great, was justified,” Jobe says, “[because] it helped the state become what it was.”

Steps Towards Healing

Every November since 1999, about 200 Cheyenne and Arapaho Sand Creek descendants have gathered at the Sand Creek Massacre Historic Site to run a 173-mile relay. As they make their way to the Colorado State Capitol, participants follow the route that soldiers took when returning to Denver after the massacre, reflecting on the atrocities that happened to their ancestors more than a century ago, even taking a moment to pause for Captain Silas S. Soule at the intersection of Arapaho and 15th Street in Denver, who told the truth about the military’s motivations during a military court hearing and was subsequently murdered. When they arrive at the building, tribal members engage in tributes and prayers to honor their historical roots. This event is called the Spiritual Healing run, and up until the surge of COVID-19, had been an integral part of the Sand Creek Massacre Historic Site’s programming.

“Before COVID, it was usually a very large event. We could have up to 200 people or more who would come to [the run]. There would be prayers offered by some of the elders of the Cheyenne and Arapaho, and it would be followed by a relay run from the site of Sand Creek to Denver,” Jobe reflects. “Now, I’ve never followed that whole route, and I don’t think it was quite the complete route, but it was large chunks of it. Then a couple days afterward, when the group got to Denver, there would be a further ceremony at the steps of the Capitol building. With the onset of COVID, that has changed a bit for health and safety reasons. Many of the tribes only send a few people to do prayers and ceremonies here at the site just to protect their communities.”

In 2014, then-governor John Hickenlooper took the healing run as an opportunity to finally apologize for the harm he and preceding government officials have inflicted on the native tribes.

“Today, we gather here to formally acknowledge what happened: the massacre at Sand Creek. We should not be afraid to criticize and condemn that which is inexcusable, so I am here to offer something that has been too long in coming, and on behalf of the State of Colorado, I want to apologize,” Hickenlooper said on that day in 2014. “On behalf of the good, peaceful, loving people of Colorado, I want to say we are sorry for the atrocity that our government and its agents visited upon your ancestors.”

Before issuing the apology, Hickenlooper collaborated with former governors to ensure that the speech was coming from an accurate, genuine place.

“That was from the state of Colorado. It wasn’t the federal government that did that, and he spoke on behalf of himself and all prior Colorado governors,” Jobe elaborates. “He’d actually spoken with the previous governors who were still living at the time just to make sure that all the governors that he could speak to were on board with that apology.”

While the apology made strides in terms of government accountability for the massacre, most feel it is merely the first step in making amends for the generational trauma and pain that descendants have endured for a century and a half.

Gale Ridgley, member of the Northern Arapaho tribe, reflects on the long-standing need for the government to do more.

“As an Arapaho person, an educator and former principal, I do believe that politics and power are stories of education,” Ridgley says. “I believe that when I go to Colorado or other places in America, it’s clear that there are still so many people who do not know anything about Sand Creek or other massacres that happen around the country. There is so much that needs to be done to heal.”

The Lawsuit

149 years.

After 149 years of generational trauma, loss and poverty, of broken promises and deception, descendants of the Sand Creek Massacre sought to gain reparations for the United States’ betrayal. In 1865, federal representatives joined Arapaho and Cheyenne tribal members to develop the Treaty of Little Arkansas, which renounced the massacre and promised compensation for family members of the victims. However, 149 years later in 2013, the Sand Creek Massacre Descendants Trust—backed by more than 15,000 identified descendants—filed a class action lawsuit under the belief that little of the money actually made it into the hands of their ancestors.

“First of all, there was a congressional appropriation [following the massacre], so Congress appropriated monies to pay for part of the damages,” explains Dave Askman, the trust’s lawyer and adopted father of two possible descendants of the massacre. “Those monies never made it to the Indigenous people; some of it actually went back into the U.S. Treasury. That may have been because they couldn’t find tribal representatives who wanted to take the money, or they couldn’t find the individuals, or they just didn’t know how to do it. I don’t know what the motives would have been of an agent of a Bureau of Indian Affairs in the 1870, but we know that the monies did not make it to the individuals who are identified in the treaties. We also found that some monies were paid to tribes. That seems on its face to be partial fulfillment of the obligations in this treaty, but paying the money to the tribes is like paying it to the government—you’re not giving it to the individuals who have agreed to get it, and no tribes are identified to receive monies in the treaty. There are individuals identified in the treaty.”

Before the lawsuit even began, the trust ran into a few challenges. Back when the search for reparations started brewing in 2012, Eric Gorski, then a reporter for the Denver Post, published an in-depth look into the case. At the time, there were four different groups all seeking justice, with arguments developing over who would qualify for the compensation.

“I think the number of different groups is a very tangible sign of the divisions within that community and frankly, so many communities,” Gorski notes. “In this case, it involves very profound disagreements—disagreements about which tribes were wronged and about when to stop counting the number of folks who would be eligible for reparations. That’s tough.”

In terms of its legal argument, the team had to find justification to sue. All the way back to the United States’ founding, a doctrine known as sovereign immunity was established, mandating that the government could not be sued without its consent or an express waiver. While no explicit language designated an express waiver in either the Treaty of Little Arkansas or the Appropriations Act that allocated its funds, much of the legislation within the Appropriations Act inferred a statute of limitations—a time limit on how long a person can sue someone for a particular cause. Thus, the trust’s legal team argued that the presence of these statutes implies consent to sue.

Ultimately, the trust’s case was not enough to convince the Colorado court. Their opinion stated that the government had not established an explicit trustee relationship with the tribes, nor was there unequivocal consent to sue in either of the cited documents. Later, in an appeal to Colorado’s Tenth Circuit Court, the lawsuit’s dismissal was upheld.

“The United States unfortunately argued successfully that the treaty did not create what they call a trust relationship between the persons identified in the Treaty and the United States. Now, I just think that that’s a gross miscarriage of justice. I think it’s absolutely wrong, and I think that the United States, when it makes a promise in a treaty, especially [with] tribes it’s in control of, [has to] fulfill those promises. Anyway, a district court decided if there was no enforceable agreement, no enforceable trust created, then the United States didn’t have to account for those monies,” Askman elaborates.

For Askman, the loss was hardly a surprise.

“When you’re a lawyer like I am, who practices Indian law, you get used to cases where you’re absolutely right on the facts, and you’re absolutely right on the equities involved in the case,” Askman says. “You’re on the right side of issues that somehow courts in the United States seem to always rule against, and they sometimes bend over backwards in order to rule against tribes. What it meant was we had to go back to the drawing board and figure out a different way to try to make our clients whole.”

The interests of the U.S. government in a case like this can’t be pinpointed, but it can be assumed that its lawyers will always protect the interests of the country.

“I can’t really speak to their motives, because I don’t know exactly what they are. There are a lot of lawsuits out there where tribes are making claims about violations of the United States trust responsibility to them, and I’m guessing they don’t want bad law on the books that might be precedent in another case. I think that, anytime you’re talking about the amounts of money that might be involved in a case like this, or if you’re talking about the amount of effort it would take to do and accounting for 150 years of mismanagement or non-payment of funds, that’s something they obviously don’t want to do,” Askman notes. “We fully expected the United States to put up a defense, and I honestly believe that, sometimes, lawyers, who are charged with defending the United States, their first reaction is not, ‘Is this right or wrong?’ but ‘How do we defend this case?’ instead of trying to figure out whether or not what they’re doing is correct.”

The battle for reparations isn’t over yet. After the legal team was struck down by yet another loss when the supreme court refused to hear their case in 2016, the plaintiffs sought out other methods to receive justice.

“There are other options available to us. I can’t really talk in detail about all of those because we’re working on them right now, but there are other branches of government. It’s not just the judicial system. If you can convince the legislature that the United States ought to keep its promises, especially to Native peoples, then maybe legislation could solve our problem. That’s certainly possible,” Askman elaborates. “There’s a possibility that an international court may hear this issue at some point. The United Nations is already aware of this case, and they sent an official to take a history from my clients, and they actually came up with the opinion that this was a wanton abuse of human rights in one where the United States really needed to make reparations.”

For the descendants of the massacre, the people that felt a duty to find justice for their slaughtered ancestors, winning the lawsuit would mean more than just money—it would mean finally living in peace.

“They’re not people who have dollar signs in their eyes. They’re not looking to get rich. They are quite the opposite, actually. They are people who are much more concerned with the United States fulfilling its obligations to the tribes and trying to close a chapter in their life which these people feel every day,” Askman says. “It’s hard to imagine, from my perspective, being so affected by events that happened to my ancestors 150 years ago, but that is absolutely the case here. It would bring closure. I know that my clients, the trust itself, would be very interested in setting up educational facilities, tribal lands or lands for persons who are affected.

“It’s now been 159 years, and they’re still looking for justice.”

Continual Strides

On Oct. 5, 2022, Michael Bennet, a Colorado senator and American attorney, joined Hickenlooper and multiple leaders from the Northern Arapaho and Cheyenne tribes in remembering the tragic events of 1864 at the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. Along with live music and multiple speakers from the members of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, Bennet and Hickenlooper proudly announced the additional funds and 3,500 extra acres of land to the site. With them was Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, the first Native American to serve as a member of a presidential cabinet.

“It is our solemn responsibility at the Department of the Interior, as caretakers of America’s national treasures, to tell the story of our nation,” said Haaland at the event. “The events that took place here forever changed the course of the Northern Cheyenne, Northern Arapaho and Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes.”

Bennet and Hickenlooper hoped that by adding land to the site, there would be more access to the public. Creating more publicity will increase the acknowledgement and education of what happened during the Sand Creek Massacre.

“This is a long overdue step to respect and preserve land sacred to the Northern Cheyenne, Northern Arapaho, Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes,” said Bennet. “We will never forget the hundreds of lives that were brutally taken here—men, women and children murdered in an unprovoked attack,” Haaland said. “Stories like the Sand Creek Massacre are not easy to tell but it is my duty—our duty—to ensure that they are told. This story is part of America’s story.”