Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Nashville in November 2025, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

Mourning and loss: the events at Sand Creek

Content warning: This article includes descriptions of the violence that occurred during the Sand Creek Massacre.

February 27, 2023

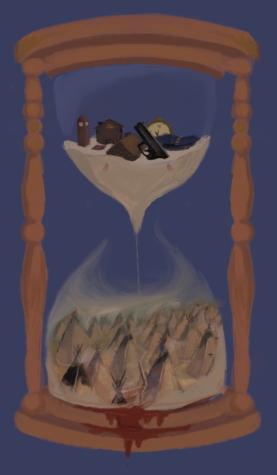

Historically, buffalo have served as the lifeblood of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. No part of the body would go unused—from the bones that were repurposed into tools to the flesh and fur that became covered tipis and lined robes. Providing warmth and sustenance over time, the buffalo has long been a sacred animal representing opportunity and prosperity.

After migrating from the Smoky Hill River to Sand Creek, the village of 750 Cheyenne and Arapaho people hadn’t seen a buffalo since they settled, meaning it had been weeks since having fresh, abundant meat.

On Nov. 29, 1864, when the sun had just begun inching above the horizon, the rumbling sound of approaching hooves abruptly awoke the sleeping tribes. A few village patrons presumptively celebrated at what appeared to be buffalo in the distance. However, the truth of what lay in the distance that morning was far from the hopeful symbol of buffalo and instead grew to be one of the most gruesome and inhumane massacres in American history.

Before

Three core tensions pervading America in the mid-19th century were simple: money, land and power. But as history has shown, these seemingly elementary entities stem issues tangled in complexity.

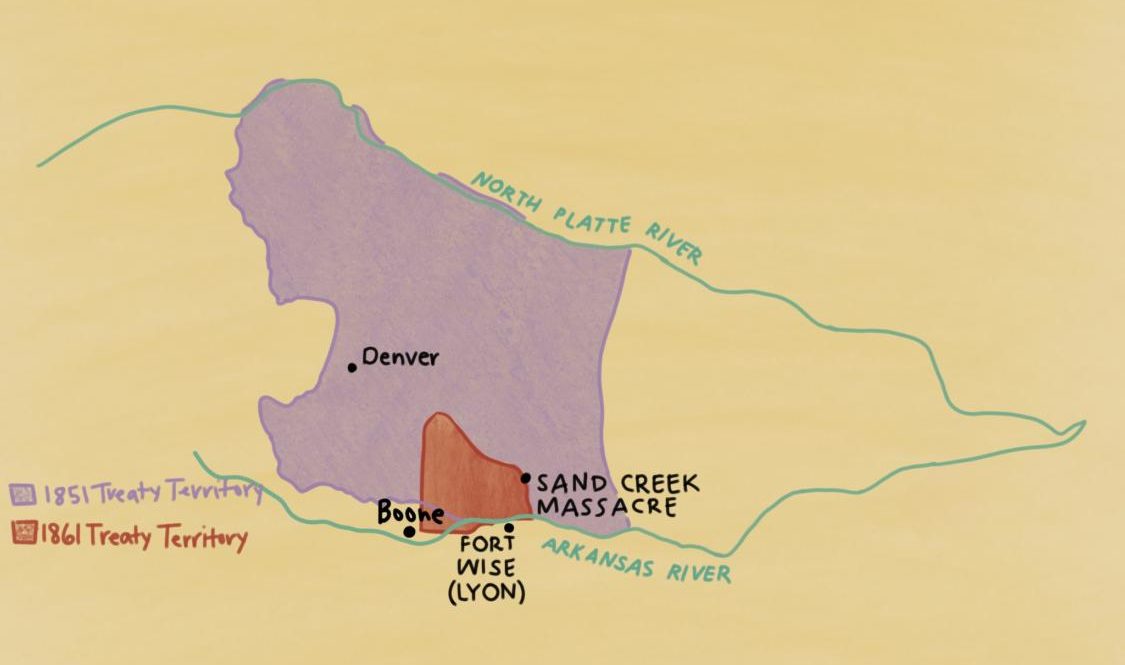

The late 1850s brought an influx of white settlers across Colorado’s Great Plains, thirsty for prospective gold in the Rocky Mountains. The settlers trespassed upon Cheyenne and Arapaho territory, which was distinguished by the Northern border of the Arkansas River and the Southern bounds of Nebraska, and diminished the area’s natural resources; land tensions between Indigenous tribes and white settlers rapidly escalated.

In 1861, the long-anticipated Civil War broke out between the Union and the Confederacy, and the federal government found itself in dire need of funding to support the war. Luckily for the government, the recent gold rush proposed a seemingly perfect solution, but at a loss for transportation, the push for a transcontinental railroad came into play in order to move the gold for use in Washington.

“One thing to keep in mind is [John Evans, Colorado Governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs at the time,] was there to build railroads,” notes Tink Tinker, a professor emeritus at the University of Denver’s (DU) graduate school, Iliff School of Theology. Tinker also served on the committee that investigated Evans’ role in the Sand Creek Massacre for a 2014 DU report. “How do you build railroads across a large piece of country that is mostly—I’m going to use the white word here—‘owned’ by Indian tribes?”

In the eyes of Evans and his supporters, Indigenous people were seen as obstacles that stood in the way of their economic and political agendas.

“John Evans was a wealthy white man. He was connected to the railroad industry, so he directly profited off of the building of railroads. In order to build railroads out west, which was a huge thing at the time, you needed to secure Native land. A huge part of westward expansion with the railroads was the removal, which often included murder, of Indigenous people,” explains Forrest Bruce, a PhD student at Northwestern and founding member of the Native American and Indigenous Studies Association. “John Evans was a person who profited off of that. It was in his financial interest for Indigenous people to lose their land so that he could build his railroads.”

On May 16, 1864, Colorado troops invaded Cheyenne and Arapaho land, killing peaceful Cheyenne Chief Lean Bear, who, just prior to the attack, had received a peace medal from President Abraham Lincoln. Lean Bear had approached the soldiers in an attempt to explain the tribe’s peaceful presence, but he was quickly shot down. The Dark Soldier Clan were the warriors that fought on behalf of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, and in retaliation, they began to attack the ranches and wagon trains of white settlers. Amidst the Civil War, there was a separate war brewing: one between the Indigenous tribes of Colorado and the Colorado government.

“Lincoln and then, of course, what the [Civil] War produced was a new vision of the nation state, and the Civil War was, in many ways, a triumph of the nation. That, in terms of slavery, was a powerful thing because it created a national government that was strong enough to abolish it,” notes Frederick Hoxie, a professor of History and American Indian Studies at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and a committee member for the DU report. “On the other hand, nationalism has produced expansion and chauvinism and hatred of people who are different from all of the rest of it. That’s the irony of it: nationalism can have two—at least two—sides.”

American nationalism was the fuel driving westward expansion, which manifested itself in different ways for different leaders. James Duane Doty was appointed to be Utah’s Superintendent of Indian Affairs in 1861 and later maintained his superintendent position while taking on the new status of governor in 1863. Doty prioritized treaties with native tribes; seeking partnership over conflict, he oversaw a commission with the purpose of crafting treaties. Nevada had a similar approach, and both states, while facing the same tensions of westward expansion between settlers and Indigenous tribes that Colorado was, managed to form effective alliances that prevented the same level of violence that Colorado exhibited.

“It struck me that Evans—his actions really were counter to the policy of the U.S. government at the time with regard to Western Indians. The government was very concerned that the Confederates wouldn’t be able to do in the west what they had been able to do in the southeast, which was to get Native American allies, to fight with them, to fight on their side. [Utah and Nevada] authorized these treaties, peace and friendship, to be negotiated and to ensure that this wouldn’t happen out west,” explains Richard Clemmer-Smith, a professor emeritus at the University of Denver and a member of the DU report committee. “Evans actually seemed to encourage hostilities.”

As tensions progressed, violence grew with it and vice versa. In June of 1864, the Hungates, family of Colorado residents, were murdered by Native Americans. Word of their murder circulated throughout the press, igniting fear and hostility in Colorado’s white population. On June 27, 1864, Evans sent out a proclamation directing “friendly” Native Americans to migrate to military outposts; he ordered the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes near the Arkansas River to move to Fort Lyon to “show them a place of safety.” The letter continues, “The object of this is to prevent friendly Indians from being killed through mistake. None but those who intend to be friendly with the whites must come to these places … The war on hostile Indians will be continued until they are all effectually subdued.”

On Aug. 11, 1864, Evans sent out a second proclamation that instructed Colorado citizens “to kill and destroy, as enemies of the country, wherever they may be found, all such hostile Indians.” In return, Evans stated that citizens could capture and keep any stolen property from the Indigenous people. On that same day, Evans was informed of the authorization by the U.S. War Department to create a temporary regiment for the purpose of battling the “hostile” Native Americans that Evans described. This became Colorado’s Third Regiment, also known as the 100-Dayers, because the group, which was formed of inexperienced volunteers, was only permitted to last 100 days.

However, due to lack of efficient communication at the time, the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes along the Arkansas River didn’t receive the first proclamation until much later. In response, Cheyenne Peace Chief Black Kettle wrote a letter that reached Major Edward Wynkoop at Fort Lyon on Sept. 6, 1864, stating his community sought peace; furthermore, the Cheyenne tribe had seven white prisoners that had been passed onto them from other tribes, and they would free the prisoners in return for peace. The mention of prisoners caused Wynkoop to lead 130 men to the Smoky Hill River, and, once there, he was outnumbered by Indigenous warriors, leaving Wynkoop with no other choice but to place his trust in Black Kettle.

On Sept. 28, 1864, Black Kettle and other Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs, alongside Wynkoop, met with Evans in an attempt to negotiate peace. Evans declined such offers, asserting that he had men already in preparation for violence. Although Evans neglected to form a treaty, Evans guaranteed them peace if they were to surrender to the U.S. army, and the chiefs did just that. They went to Fort Lyon and surrendered to Major Wynkoop in order to insure their protection against violence from the U.S. government.

At Fort Lyon, Wynkoop provided the hundreds of Cheyenne and Arapaho people with food, but once Wynkoop’s superiors discovered that he was feeding the tribes, his position at Fort Lyon was given to Major Scott Anthony, who began to feed the Cheyenne and Arapaho people as well. Knowing that the Colorado government deemed it illegal to provide Native Americans with food, Anthony instructed Black Kettle and accompanying Cheyenne Chief White Antelope to reside in Sand Creek, which existed 20 miles from Fort Lyon, where the Indigenous people would be able to hunt for food. He also provided the chiefs with a white flag, which could be used to indicate their peacefulness to government officials. The tribes were to remain in Sand Creek until Anthony came to give them further directions, but Anthony never came, and instead, the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes were met with a horrific surprise.

During

By the end of November, the time limit on the Third Regiment was reaching its end, and Chivington grew impatient as jokes about the 100-dayers’ lack of action grew stronger, receiving the nickname “Bloodless Third.” Commanding the approximate 250 soldiers from the First Regiment and approximate 425 soldiers from the Third, Chivington marched the men—the majority of whom were heavily under qualified volunteers—to Fort Lyon.

“It’s a specially raised regiment of troops under a simply sadistic madman with career ambition,” notes Northwestern History Professor Carl Smith about the 100-dayers.

On Nov. 28, 1864, Chivington and the Third Regiment reached the fort in search of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. Anthony informed Chivington that they were at Sand Creek, and they were a peaceful tribe that complied with the government. Chivington ignored all agreements with the tribes and marched his men over to Sand Creek.

“Chivington knew exactly where they were, and Chivington needed a quick victory against Indians in order to satisfy the political climate, so he decided to attack this peace village early in the morning,” Tinker says. “John Evans spent the summer building the public up for making war against Indians, any Indians. Evans and Chivington both, but Evans particularly, divided Indians into two groups: ‘friendlies’ [and] ‘hostiles.’ Hostiles are those who refuse to surrender their homes to the white advance, and friendlies are those who got out of the way. Well, those at Sand Creek were actually friendlies, but John Chivington got to qualify them as hostiles, because Indians don’t decide which are hostile and which are friendly. That’s entirely up to the discretion of the white men.”

To Chivington, peace and promises meant nothing, his one pursuit was violence. He instructed his troops to kill every Native American, including infants and children, because according to a 1864 speech he gave in Denver, “Nits make lice.” One of Chivington’s main officers stated, “When we came upon the camp on Sand Creek, we did not care whether these particular Indians were friendly or not.”

At the first glimpse of sunrise, Chivington and his men attacked the sleeping village of approximately 750 Cheyenne and Arapaho people.

Upon their arrival, Black Kettle ran to meet them with the American flag and white peace flag, indicating that the tribes were protected, as they had done what they were told to do by surrendering to the U.S. Army.

“When I looked toward the chief’s lodge, I saw that Black Kettle had a large American flag up on a long lodgepole as a signal to the troop that the camp was friendly. Part of the warriors were running out toward the pony herds and the rest of the people were rushing about the camp in great fear,” reads an eyewitness report from George Bent, a half-white half-Cheyenne survivor of the massacre. “All the time Black Kettle kept calling out not to be frightened; that the camp was under protection and there was no danger. Then suddenly the troops opened fire on this mass of men, women, and children, and all began to scatter and run.”

The Cheyenne and Arapaho people began digging holes in the sand to jump in and hide, while others ran up the bed of the creek. The village was a Chief’s village, where over 20 Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs lived, so the majority of the village’s population was composed of women, children and elders, who stuck by the chiefs for protection. Consequently, the village was left nearly defenseless against the troops, as Cheyenne and Arapaho men who were in condition to fight were scarce.

White Antelope was the first chief that the troops murdered. Unlike many of the scattering Cheyenne and Arapaho people around him, White Antelope remained at the scene, approaching the troops with his arms open, singing, “Nothing lives forever, only the earth and the mountains,” right before being shot down. In 1851, White Antelope had received a peace medal in Washington D.C., and now, he lay dead, as the malicious volunteers terrorized the community around him and cut off his genitals to keep as trophies, memorializing their gruesome acts.

Captain Silas Soule and Lieutenant Joseph Cramer from the First Regiment refused to contribute to the violence, ordering their troops to hold fire. Later, they reported on the atrocities they witnessed. In Soule’s testimony, he stated, “I heard a soldier say he was going to make a tobacco pouch out of them,” in reference to White Antelope’s castration.

In a letter sent to Wynkoop two weeks after the massacre, Soule wrote, “hundreds of women and children were coming towards us, and getting on their knees for mercy.” He witnessed children “have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized.” He described seeing, “two Indians [take] hold of one another’s hands, chased until they were exhausted, when they kneeled down, and clasped each other around the neck and were both shot together, they were all scalped, and as high as half a dozen taken from one head. They were all horribly mutilated. One woman was cut open, and a child taken out of her, and scalped.”

Four days later, Cramer wrote a similar letter to Wynkoop in which he detailed soldiers cutting fingers off of dead Indigenous people to steal rings and shooting women and children who pleaded for mercy. Cramer also begged Wynkoop to deny Chivington the position of brigadier general, explaining that Chivington anticipated the promotion.

The violence continued for nine hours, killing a total of approximately 200 Indigenous people with a similar estimate injured. The majority of casualties were women and children.

“There’s a famous painting in 1872, painted by John Gast, sometimes called [American Progression], and you’ll see the Angel of Progress coming across the painting. You’ll see cities binded to the east and fleeing wildlife: wolves, deer, buffalo and Indians—part of the ‘wildlife’—flee out of the way of this Angel of Progress as she sweeps across the continent,” Tink describes. “That’s the American romance, and unfortunately, it wasn’t that sweet—especially if you’re an American Indian.”

After

Federal policy regarding western territories, as well as government presence in the area, was considerable, so when word of the massacre spread to government employees, they were quick to report what happened to the capital. While local newspapers, and Chivington himself, hailed it as a triumph against the “savage” Natives, federal officials were far more scrutinizing and wanted a further investigation of the event.

By early 1865, a military investigation of the massacre was underway, and it was clear to Chivington that he would need to justify his actions. However, it seems that he overestimated his position and assumed that the blame would fall on Evans. Chivington’s beliefs were not unfounded, since local newspapers and settlers had praised his actions as “peacekeeping.” What he didn’t realize was that Evans’ relationships in government initially kept him shielded from scrutiny, and since there was no proof that Evans had ordered the massacre, Chivington would get the blame.

Despite never being put on trial, Chivington would become the subject of a military investigation, during which he sought to create the image of a large and dangerous Native military force. He claimed there were 1200 Natives, mostly warriors, 700 of whom were killed. In actuality, modern estimates put the number of Natives present at Sand Creek at around 750, and almost all of them were women or children.

During the investigation, he testified that the Natives were responsible for killing whites, along with causing hundreds of thousands—today millions—of dollars in property damage. Chivington’s claims were nothing more than fallacy, as the Natives at Sand Creek had earlier surrendered themselves peacefully under the provisions of the peace talks at Fort Lyon. He also claimed that he possessed “the most conclusive evidence” of a hostile military alliance between the Sioux, Cheyennes, Arapahoes, Camanche River and Apache tribes. At this point, however, organized cross-tribe resistance to American dominance in the region was either severely weakened or nonexistent, and Chivington exaggerated to exacerbate fears of Native revolt. Chivington’s version of the Sand Creek story is a reflection of himself, one that seeks to frame him as a hero and protector of whites in the region.

Evans too was admonished but never at quite the same level as Chivington. Evans had the advantage of having friends in Washington, namely Ohio Congressman James M. Ashley. Ashley wrote an appeal to Secretary of State William Seward which argued that the criticism of Evans was unjust because “Gov Evans was not in the territory at the time and could not be responsible for the acts of any military officer acting under the direction of a Major General of the United States army,” according to the 2014 DU report.

The shadow of Sand Creek followed Evans throughout his life, but he consistently downplayed his role in the massacre.

“We know that 20 years later in an interview with a famous historian in California that John Evans told the historian: ‘however you judge the Sand Creek Massacre, the one thing we know is that it was successful in securing Colorado territory,’ or white Christian occupancy, so he’s unrepentant,” Tinker shares.

Evans tried to rewrite the very perception of the massacre when he testified to the Secretary for War in the aforementioned military investigation. He attempted to define the massacre as an honest mistake by Chivington in differentiating “peaceful” Natives from “hostile” ones.

“While a general Indian war was inevitable, it was dictated by sound policy, justice, and humanity that those Indians who were friendly, and disposed to remain so, should not fall victim to the impossibility of soldiers discriminating between them and the hostile, upon whom they must do any good, inflict the most severe chastisement,” Evans stated at the time.

In other words, Evans is asserting that conflict with the Natives was inevitable, and the government couldn’t tell the difference between those resisting American expansion and those submitting to it.

However, not everyone involved at the time complied with the rhetoric of Evans and Chivington that justified the events, both leading up to and taking place, at Sand Creek.

In 1865, Soule testified before a military commission that was ordered to inquire into the Sand Creek Massacre. His candid testimony revealed an ugly truth behind the Sand Creek Massacre that Evans and Chivington had previously masked through their propaganda.

In contrast with Chivington’s description of a village full of “hostile” Indigenous warriors, Soule shared an opposing narrative.

“[The Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes at Sand Creek] said they were desirous of making peace with the whites,” he noted. He also continued to explain how other other officers at Fort Lyon felt similarly to himself in holding Chivington responsible for the violence that took place. “I heard them say that [Chivington] ought to be prosecuted, and that, when the facts got to Washington, he was liable to be, or words to that effect.”

Soule’s testimony was one component of a larger report by the Secretary of War, published in early February of 1867, that concluded that Chivington and Evans were both at fault in regards to the Sand Creek Massacre. Following Soule’s testimony, Chivington resigned from the military before he could be put on trial, voiding him of legal consequences. Evans was removed from his governorship of Colorado in June of 1865. Likewise, Evans tried to distance himself from the massacre and those involved, but his efforts couldn’t save him from the pressure to resign.

While Evans and Chivington were dishonest about their role in the massacre, Soule strived to tell the truth, and he paid a deadly price.

On April 23, 1865, a few months after the trial, and soon after Soule was married,

he went to explore a gunshot heard nearby. When Soule got there, he was greeted by his murderers and fatally shot. Though it hasn’t been proved, it is speculated that Chivington hired men to kill Soule because the two that were arrested, and eventually escaped before the trial, had been part of Chivington’s army.

Evans and Chivington lost their positions; Soule lost his life. Once again, the atrocities committed against Indigenous tribes became buried amongst the thirst for land, money and power.

“Two different worldviews,” Tinker describes, in regards to the views of white settlers and Indigenous tribes. “Unfortunately, one of them gets to eat the other and totally erase it.”