Teaching the 2020 Election

November 16, 2020

2020 has been an eventful year. The constant news has led to countless classroom discussions about world events, with the election chief among them. As in years past, students and staff have used the election as an opportunity to shed light on aspects of the curriculum and engage students in current events.

“I just find that students are much more interested in current issues.… The kids just have a real thirst for talking about the election. It really stimulates good discussion,” AP Government and Politics teacher David Feeley said.

These discussions can range—based on the class in question—from conversations about the specifics of the election, the general process behind the electoral system and the work that students can and are doing to support causes they believe in.

“We talk about the historical treatment of how we have a president… [how politics] touches every piece of our society… the legislature, the Supreme Court… how people become president, how they raise money, how they develop an image in the media, how they get endorsements, polling, all of that are things that play into how one becomes president of the United States,” AP Government and Politics teacher Darlene Gordon said.

In addition to talking about the specifics of the election process, many teachers have focused on the issues and tactics that students can use to have informed political discussions within and beyond the classroom.

“We’ve been talking about [the election] in environmental science, just because that class pretty much only talks about politics because the environment, unfortunately, is a political opinion,” senior Mia Houseworth said. “We [also] talk about how we’re feeling [and] how to cope with election anxiety.”

Regardless of the topic of conversation, teachers are expected to hold the rules, to stay neutral, not express their personal opinions, and allow all perspectives to be shared and discussed with civility.

“Anytime we’re talking politics, a school has a fine line to walk… [We won’t endorse a candidate] but what we can do is really help students learn to examine the issues, the candidates, the policies. Help you think about if you base your support or your opposition to a candidate based on a political commercial, or if you actually find out something about those candidates.” Superintendent Eric Witherspoon said.

Finding balance between properly educating students about politics without influencing them is a difficult task. Some teachers choose to refrain from voicing their opinions, some choose to talk about the issues more than the people they believe to be causing them, and others choose to say what they believe while leaving space for disagreement and different opinions.

“Normally, my view is if you asked me what my politics are… I will share those opinions after the kids have kind of had a chance to get their [thoughts in], but I’ll also say, tell me if you disagree, let’s discuss it, let’s look at all the viewpoints,” history teacher Andrew Ginsberg said.

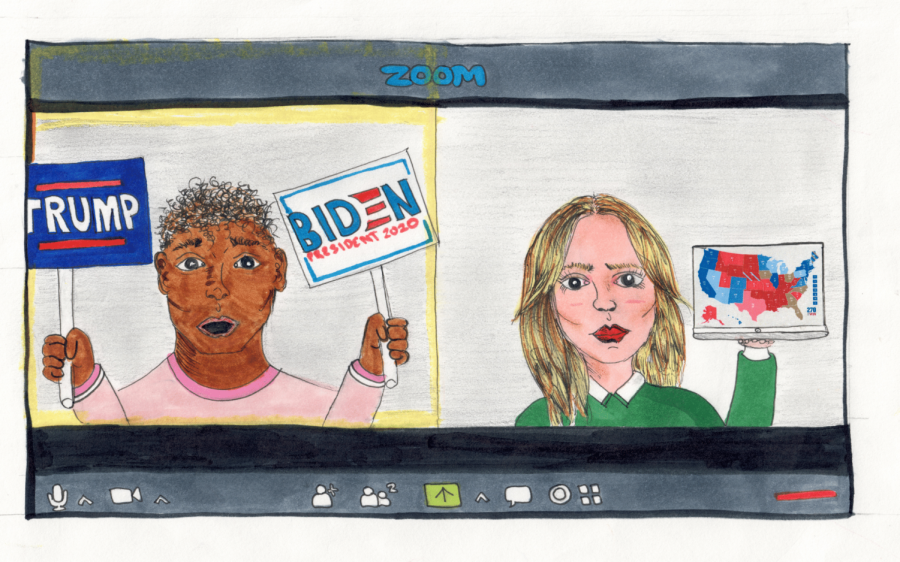

Choosing to lead an open ground discussion can encourage a more well-rounded conversation about the election by ensuring that it is being tackled from all angles. However, it can also lead to conflicts between students who hold fundamentally opposed beliefs.

“Evanston is a liberal, Democratic town, but you do have conservative families who are Republican loyal, [even if they aren’t] Trump loyal. The moment somebody says, ‘I’m a Republican,’ or ‘I believe in a conservative ideology,’ there’s an argument, there’s a fight. I have really had to be cognizant of that and play mediator between some of my students to keep the peace,” Gordon said.

While the role of the teacher as a mediator is a viable one, the neutrality it creates can lead to uncomfortable and triggering moments for students who feel that tolerating hateful opinions should not be part of school policy.

“I feel like most [teachers] are doing the best they can. We are at a kind of unprecedented [moment] in history, and during any other presidential election, I would say it would be their job to be neutral—I think it’s probably still their job to be neutral—but… I’m almost frustrated by the abundance of forgiveness for being on whatever political side you are on. I have respect for Republicans, but I have no respect for Trump supporters, because [even if you aren’t] racist or homophobic or misogynistic, you decided that wasn’t a deal-breaker,” senior Callie Stolar said. “I wish there was a little bit more [against that] and especially like seeing [a student in one of my classes] that has a blue lives matter flag [in his background]…. I just can’t believe that’s tolerated.”

This is a dilemma that faces many teachers: how can you teach respect and honor the humanity of your students while maintaining a neutral perspective?

“We’re not supposed to [express our political opinions], but I don’t think it’s doable now or here. I don’t think we can have a push for racial equity and not talk about the president,” Ginsberg said.

Given the framing of this election as a fight against hatred and for a nation that embraces and accepts diversity, teachers need to discuss how politics intersects with race, gender, sexuality and other student identities, but this in-and-of-itself is a political act.

“This particular election carries a lot more weight because of the rhetoric that we’ve been hearing from the Trump administration, some of the policies that we’ve been witnessing, the attack on people’s identities that this administration has been engaging in…. My teaching really revolves around interrogating the past and being honest about our past, so that we can actively work towards making better decisions that humanize one another instead of perpetuating racism, anti-Blackness, white supremacy, homophobia, transphobia and a lot of the oppressions that exist in our society today,” history teacher and SOAR sponsor Corey Winchester said.

Teaching an election is political; ensuring that students understand the reality of the world around them requires honesty and courage, but it is work that teachers at ETHS and around the nation engage in time and time again.

“We need to be honest in our life, and our school goes through these courageous conversations all the time,” Feeley said. “How is politics less of a courageous conversation?”