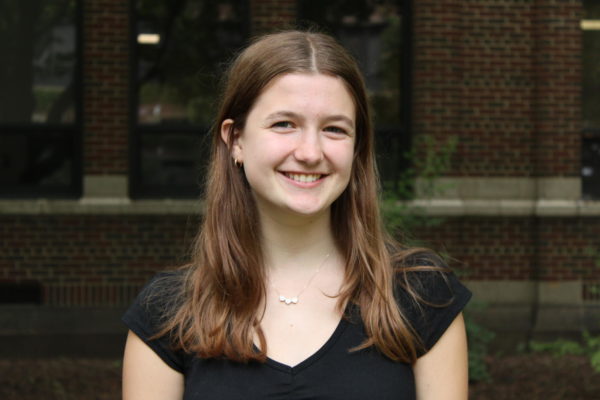

Elizabeth Hartley is a woman of many hats.

One—most familiar to the hundreds of students that have passed through her classroom—is for teaching. One is for farming. One is for interior design. One is for motherhood. One is for activism. One is for learning. The list goes on.

Hartley would gladly put on each of her hats in order to share pieces of her storied past with an eager listener. Her anecdotes are a keystone of her class experience; no student escapes her mentorship without hearing countless snapshots of her remarkable life.

She had an unusual path to a teaching career, and it all began with an unconventional childhood in San Diego, California. After facing the loss of her parents at a young age, Hartley and her three sisters moved in with her aunt and uncle, who became her mother and father.

“We did the most insane, the most unsafe stuff,” Hartley remembered. “Our first camping vehicle was an army ambulance from World War ll. My [adoptive] dad put the two jump seats from the back part of the ambulance on the roof and bolted them in. When we got across the Mexican border, he would put my sister and I in them, strap us in, and go flying down the highway.”

Much of Hartley’s adolescence was as precarious as a whirlwind rooftop drive—between the volatile guardianship of her uncle and exciting trips to ski, sail, and surf, her years in San Diego developed an appreciation for the unexpected.

Her next “hat” was that of a college student, as she enrolled in the University of California-Berkeley in 1972, while protests of the Vietnam War were in full throttle. Within months of being on campus, Hartley’s view of the world was upended. Swept along in the tumultuous political climate, she found her passion for advocacy.

“The whole world was exploding on the Berkeley campus. I was born and raised by a bunch of super conservative Southern Californians. When you’re that age, your family is a big piece of you,” Hartley said. “I went to Berkeley campaigning for Richard Nixon, and by election day, I voted for George McGovern.”

From San Francisco, her marriage to a fellow Berkeley graduate took her to the opposite coast—specifically, to Washington D.C.—before settling in Evanston. She began her work as an interior designer in the early 1980s, using skills of “intuitive good taste” to advise a growing clientele. Her practical experience convinced her that it was time to return to school.

“The more work I did, the more I figured out what I didn’t know,” Hartley said. “I’m kind of school-happy. I love school. My way to avoid not paying back my federal student loans is to stay in school,” she joked, “because they suspend payments if you start another degree. That’s a pretty good plan, right?”

Hartley enrolled at the Harrington Institute of Interior Design, where she earned her design degree, and built her life in Evanston, raising three children. In her downtime, she earned a BFA in photography from Columbia College. Soon, however, she was itching for something new. After her divorce in the mid-1990s, Hartley was doing design work for the then-chair of ETHS’ English department.

A fateful phone call from the department chair was Hartley’s—literal—call to adventure. Asked to fill in as a substitute English teacher, for which all was required was an undergraduate degree, Hartley used her love of literature to teach her first-ever semester of class.

“I was like, ‘I can do this! Give me the books, I’ll read them,’” Hartley said. “Then I walked on. With no teaching degree, no English degree.”

However, by then Hartley had already committed to move out of her current home for a change of scenery in the Wisconsin countryside, so her journey towards the classroom hit a detour. Under the encouragement of several friends, she planned to start a farm. With no agricultural experience, but the support of knowledgeable peers, she bought a property and began her mission to make a living off the land.

“My hippie girlfriend from Cal, she’s the one that got me started on the animals,” Hartley recalled. “She was doing work for Disney, a documentary on Willie Nelson, and she called me up one day and asked me to go with her to [Nelson’s] ranch in Austin. Well, we got down there and he was gone. But we went to a goat farm instead, and she said, ‘Here’s what you’re gonna do: You’re gonna buy a farm and you’re gonna buy a bunch of goats, and you’re gonna make goat cheese.’ And I said, ‘Aye, aye, captain!’”

(Of course, anyone who has passed Hartley’s classroom knows that it was alpacas, not goats, that she ultimately settled on raising at her farm. The large, stuffed alpaca that takes residence by her projector and the proudly displayed photos of two of the animals on her door make this clear. The goats didn’t work out, but luckily Hartley’s friend had the suggestion up her sleeve a few years later.)

After beginning her efforts on the farm, Hartley moved back to Evanston for her youngest daughter’s first year of high school. Yet, her work consulting with a furniture company wasn’t fulfilling, so she returned to her substitute position at ETHS.

Every day, leaving the school building, she would ask herself questions of “Am I happy?” and “Did I have fun today?”

“If I don’t like something, I’m out. I don’t stick around and be miserable,” Hartley said. “Now, do I have much to show for that? No, but ‘jack of all trades’ is not a bad thing.”

Her findings were overwhelming: she did enjoy teaching. In fact, she enjoyed it so much that she pursued a fourth degree, this time a teaching certificate from DePaul University. After graduation in 2006, she was hired as a full time teacher at ETHS, and she has not left since.

“Part of it was logistics,” Hartley admitted. “I wasn’t at a stage in my life where I could give up my years of service to Evanston and move somewhere else. Part of it is a strong commitment to this community, because I’ve lived here for a long time and raised my kids here. But also, the amazing thing about the career of teaching is that your work is actually your activism, if you choose for it to be.”

Hartley had found an outlet for her desires to challenge the norm and productively discuss controversy. Through her teaching career, she has pushed students to think outside the box, fostered love for literature, and advocated for departmental change.

“People like to make noise,” Hartley said. “I like to make noise. I like to be seen, I like to be heard, but what we need is people that are willing to practice listening.”

Prior to recent years, the freshman Humanities curriculum at ETHS included Honors classes that were offered to the top 5 percent of standardized test takers with teacher recommendation from middle school. While the course was intended to challenge advanced students, it resulted in segregation, as children of higher socioeconomic backgrounds were more likely to be placed in the Honors sections.

Some staff members, including Hartley, protested the use of Honors Humanities. After a controversial debate, the school decided to eliminate tracking, pooling all incoming freshmen into earned-honors courses.

“It was super hard, and it was super contentious,” Hartley said, “but I was really blessed to be able to be a part of that. Because if I hadn’t chosen to go to work as a teacher in a public high school in a diverse community like Evanston—if I chose to remain an interior designer—would I ever have had the opportunity to have something like that happen in my life? Definitely not.”

Hartley’s teaching philosophy is built on honesty and respect. She is unafraid to be conversational, blunt, and express her care for her students.

“It’s scary to give up your power,” Hartley said. “I think that’s behind a lot of the resistance to being ‘human’ on the part of teachers. Because if you are human, you are essentially leveling the playing field.”

This year, Ms. Hartley dons another graduation cap, this time to say goodbye to her 22 years at ETHS. Her passion for helping students is not leaving with her. She plans to spend her time at her farm in Wisconsin, potentially opening campsites on her property, hosting summer programs for incoming seniors working on college applications, or remotely reviewing for admissions departments.

“My youngest sister and I are the only two people in our fairly large extended family who’ve ever left San Diego and developed another layer of identity than just ‘those crazy Hartleys from San Diego,’” Hartley said.

“Another layer” is an understatement: Hartley has embraced her “jack-of-all-trades” mindset and is unafraid to take on more challenges. Between all that she has accomplished and all she has yet to give a try, the future is bright for Ms. Hartley.

“Pick a career path, any career path. [Teaching] is a wide open playing field,” Hartley said. “I’m grateful for my career. I wouldn’t have it any other way. I don’t feel resolved. I’ll feel resolved when I’m dead,” she laughed.