Opinion | Nutrition curriculum promotes diet culture, unhealthy eating

October 14, 2022

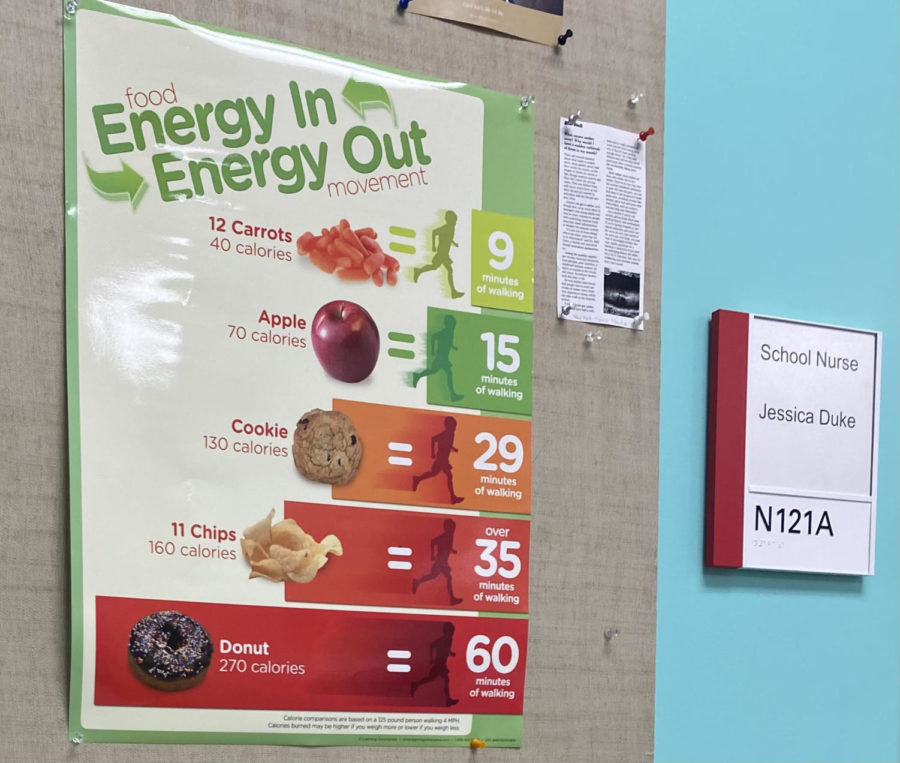

Whether the result of an injury or to drop off a doctor’s note, no student wants to find themselves sitting in the nurse’s office. However, one element makes the trip at ETHS particularly distressing—a sign informing readers of exactly how long they need to walk to burn off the calories of specific foods.

Although seemingly harmless, signs like these that promote exercise for the purpose of burning calories can eventually lead to unhealthy food restriction and negative impacts on self-esteem. In a society where eating disorders will impact more than 13 percent of girls between the ages of five and 20, ETHS, like most other US schools, places far too much of an emphasis on ideals that feed into diet culture.

Ultimately, this issue extends out of the nurse’s office and into the classroom. For as long as students can remember, the P.E. nutrition curriculum has utilized fear to alter eating habits. Students have been taught that certain foods, such as sugars and fats, should be kept out of diets, that high-calorie foods are inherently unhealthy, and that, if one were to consume these foods, there would be a negative impact on their health—all ideas that are blatantly false.

Senior Violet Weston recalls that much of the curriculum even goes as far as to mimic a diet.

“The way ETHS teaches nutrition is structured in a way that doesn’t take into account that everyone eats differently and needs different things for their body. And [the wellness classes] also put an emphasis on certain foods being ones you shouldn’t eat, or label them as bad, when really they are okay, and only over consumption of food groups could actually be negative,” Weston says. “I remember the strong emphasis that our teacher had on not eating processed sweet foods, repeatedly saying how terrible these foods were for you. We were instructed to track our eating and follow the rules of what the teacher considered eating healthy. This included, as we were advised, having a ‘treat day,’ where you are allowed to eat the sweets that you are cutting out throughout the week. It sounds awfully similar to a diet.”

So, why is teaching teenagers to diet such a problem? Well, besides the more obvious implications that such lessons could cause some to develop disordered eating patterns, in general, any sort of changes in youth nourishment can lead to negative impacts on both physical and emotional health. During a time when bodies are still developing and weight loss is rarely recommended, students are already taught to track their food intake and create meal plans.

In fact, one research paper from the Pediatrics & Child Health Journal explains that “in growing children and teenagers, even a marginal reduction in energy intake can be associated with growth deceleration. Disordered eating, even in the absence of substantial weight loss, has been found to be associated with menstrual irregularity, including secondary amenorrhea in several cross-sectional studies. The long-term risk of osteopenia and osteoporosis in dieting girls, even in the absence of amenorrhea, is of considerable concern as well.”

When it comes to disordered eating, the problem shows up as a two-fold. For students that have already struggled with eating, either currently or in the past, discussing such topics can harm their recovery, but for students that do have a healthy relationship with food, these lessons could be exactly what changes that. For instance, Rogers Behavioral Health has found that 15 percent of its patients regard school nutrition curriculum as what fostered their eating disorders.

“We were told to count the calories, sugar and fat on foods that we had in our houses, and the food tracking that we were told to do throughout the day, for myself and my friends included, put a lot of pressure and judgment into eating normal foods,” Weston elaborates. “Feeling guilty about eating carbs and all the foods that were simply deemed as bad in the class was a reality. As someone who has struggled with disordered eating, and took the class with people that I knew who also did, I have to say that the class massively impacted my disordered eating in a detrimental way.”

Thus, the very lessons that are there to promote “healthy” eating have had the exact opposite result. Every task that Weston and her classmates were instructed to complete—counting calories, cutting out processed sugars, and labeling certain foods as good or bad—are all symptoms that NEDA recognizes for eating disorders. In fewer words, ETHS is literally teaching young, impressionable students how to have an eating disorder.

Even throughout adulthood, these recommendations have very little truth to them. In a 2021 Good Housekeeping article, registered dietician Stefani Sassos explains that every food serves a benefit to one’s holistic health—whether it be for the nutritional value or, simply, that the food invokes a positive reaction.

“Some foods have ingredients that aren’t as nutritious for the body, like trans fats and artificial additives, but that doesn’t mean we should form strict and rigid rules around avoiding those foods for the rest of our life or attaching morality to food,” Sassos says in that article. “You are not a better person if you eat a more nutritious food, and you are not a worse person if you eat something that is less nutritious. Life isn’t perfect and involves making choices that take your circumstances, tastes and preferences into account.”

Unfortunately, ETHS has blatantly failed to tell this multi-dimensional narrative, focusing on the unlikely consequences of eating certain foods, rather than the benefits of eating items that do have more nutritional value. However, the worst example of this fear mongering technique would have to come from the P.E. Department’s “Sugar Show” from last year—a presentation that worked to convince kids that, as developing high school students, they should cut sugar out of their diet.

For junior Evelyn Koski, this presentation was especially detrimental toward her wellbeing. Since before she can remember, Koski has struggled with an eating disorder—visiting food therapists and seeking treatment as early as elementary school. But, despite all of the various challenges Koski had to overcome these past years, the ‘Sugar Show’ proved to be one of the worst yet.

“I have never felt as bad about my own eating as I did when watching [the Sugar Show]. Being told that I will suffer forever in my life if I don’t stop eating what I honestly need to eat made me feel sick; I could not eat right for a few days after,” Koski says. “The Sugar Show relies on fear and guilt to trick you into eating healthier, [but] I doubt it has ever once inspired a teenager to change their eating habits overnight.

Although she informed her teacher of this and asked to be excused from the presentation, Koski was then forced to sit through it for a second time.

“I asked my teacher the second time last year if I was allowed to simply sit in the hallway, and was told if I did I would be marked absent from class and have to make it up with exercise later,” Koski elaborates. “I don’t ever want someone else struggling with eating [to be] forced to watch that like I was.”

Both Koski and Weston also noticed similar problems with the wellness classes misrepresenting disordered eating.

“The group assignments for studying disorders, such as anorexia, were triggering. Working in a group of five or so people to make a presentation on something you suffer from or can relate to is hard, because some people take it lightly and with a grain of salt, not respecting the seriousness or reality of it, and are really insensitive, which can be harmful,” Weston elaborates. “Someone who I know was recovering from an eating disorder was placed in the anorexia presentation group, and they asked to be removed from it, [to prevent] triggering anything in their recovery. Regardless, they were still placed in that group, and it ended up triggering thoughts that they were working to get rid of, not to mention they had to work with a group of people that were acting insensitively.”

“There was no effort to discuss eating disorders outside of my own, when I took it upon myself to teach the class about my own struggles with eating. They ignored what I had said and tried to tell me the exact opposite, even though I was talking about something that I personally struggled with,” Koski adds.

Besides promoting unhealthy eating habits through lessons such as the Sugar Show, the nutrition curriculum additionally feeds into negative feelings about body image. In some classes, students are asked to determine their BMI, and then, based on the numeric value of it, could be advised to lose weight.

One particular assignment that students have been asked to complete reads, “You can use an online calculator to figure out your BMI. If you are in the overweight or obese category, try to lose some weight.”

Recommendations pertaining to weight loss and eating should only ever be made by health professionals—not a random ETHS teacher that doesn’t know the full history behind a student’s health and body composition. Such actions do nothing but make students feel bad about their bodies when, almost every time, there isn’t an actual need to lose weight.

“Promoting diet culture and pushing students toward healthy eating are two different things, and clearly, ETHS’ success in promoting healthy eating with the way they teach wellness classes has been poor,” Weston concludes.