Letter from the Editors | Acknowledging education’s origins is key to moving forward

December 16, 2022

When Mayra Bazan Gonzalez was suspended for ten days and recommended for expulsion for carrying pepper spray, the conversations in The Evanstonian office that followed compelled us to investigate the various ways education has operated as an institution—yielding power, influence, and control—to create a negative environment for marginalized students. Since its beginning, traditional American school has operated to instill conformity, whiteness, and assimilation within its students. Following the enactment of The Civilization Fund Act in 1819, Native American youth were forced to leave their reservations and attend American Indian Boarding Schools to aid in the so-called “civilization process.” Upon arrival, indigenous youth were given Anglo-American names, mandated to convert to wear military-style clothing, bathe in kerosene, and shave their hair. According to The Indigenous Foundation, at school, “Male students were taught to perform manual labor such as blacksmithing, shoemaking, and farming amongst other trades. . . Female students were taught to cook, clean, sew, do laundry, and care for farm animals. Standard academic subjects like reading, writing, math, history, and art were also taught, however, these subjects emphasized American beliefs and values. For example, students were taught the importance of private property, materialized wealth, and celebrating American holidays such as Columbus Day.” If students did not confine to the assimilation process, they would be subjected to extreme punishments, including beatings, extreme labor, and physical, sexual, and spiritual abuse. Boarding schools also had notoriously bad living conditions. Because food and medical attention were scarce, children were malnourished, overcrowded dormitories proliferated infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, flu, and trachoma, and more than 500 students died as a result. Parents were rarely notified of their child’s death, intentionally kept uniformed of the torture their children endured. Those who survived lost their cultural identity, sense of safety, and years of childhood all for the purposes of creating a white national identity.

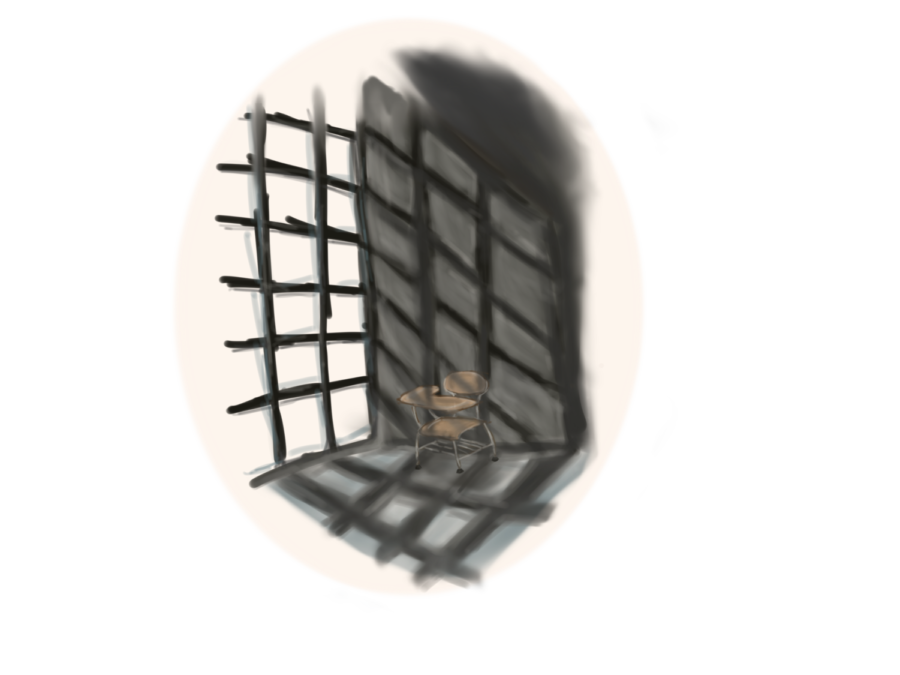

In more recent decades, marginalized students are forced to act uniformly in schools by way of policing. When the Reagan Administration announced a “War on Drugs” to expunge crack-cocaine and cocaine use in America, it allotted greater power for penal systems to disproportionately criminalize Black and brown men. Unfortunately, seeing how schools have always functioned to inflict control and suppression, adopted Raegan’s strategies of policing in what sociologists call the “school-to-prison pipeline”. In this concept, students, particularly Black and brown students, are pushed out of the school system and into the criminal justice system through targeted disciplinary policies. At ETHS, this system of policing is pertinent. According to Propublica, Black students are 10.5 times as likely to be suspended as white students, and Hispanic students are 5.9 times as likely to be suspended as White students at ETHS. However, nationally, Black students are suspended at three times the rate of white students—putting ETHS in a worse position than the national average. In a report entitled “Reimagining School Safety”, the Moran Center writes, “There have been at least 30 arrests made on ETHS property, although Black students at ETHS comprise approximately 25% of the population, they make up 77% of the arrests.”

As a publication, it is important that we address and reconcile with the historical origins of school in order to move forward. For ETHS to commit to genuine school safety, we must acknowledge its faults—and that begins by sharing personal narratives of students that have been disenfranchised. With that said, we would like to provide a brief overview of our stories prior to your reading of them.

Our first story focuses on the ways in which ETHS’ classification of pepper spray as a weapon targets female-identifying students. Our second story looks at the racial profiling and implicit bias present in the schools’ disciplinary staff, and how the ETHS Pilot ignores the nuances of race and gender when deciding what weapons to criminalize. Our third story focuses on the classroom, where a Black student shares her experience of not feeling safe and understood in AP classes. Our fourth and final story discusses the importance of intersectionality when navigating safety in school given the politically charged nature of power as it relates to slavery, patriarchy, and sexual orientation.

As you read these stories, we hope that you feel inspired to discuss the history of education and use it to inform your actions and beliefs. Additionally, we want to acknowledge that we did not cover all facets of safety in schools in this issue. To gain a more comprehensive understanding, we encourage you to engage with resources like podcasts, books, websites, and movies. We hope that you find meaning in these pages and we appreciate your willingness to go through this journey with us.

– Meg Houseworth, Sophia Sherman, Maddie Molotla