Evanston’s Guaranteed Income Program, often overlooked because of macroscale projects in Chicago and Cook County, began as a pilot program around 10 months ago, with the first $500 payments sent out on prepaid debit cards in early December 2022. The program, created in tandem by Northwestern and the city, is a form of universal basic income–a welfare proposal where the government gives an unconditional installment to its population.

A team of graduate students at NU–Phoebe Lin, Claire Mackevicius and Sheridan Fuller–joined with a professor in the School of Education and Social Policy, Jonathan Guryan, to study the program’s impact and viability for the City of Evanston long-term. Their results are still incomplete as the year-long pilot hasn’t concluded, but there were massive observable advantages from the first few months alone.

“A lot of the discussions about this item include the word ‘universal,’ which does not describe the programs at all,” said program proponent and Evanston Mayor Daniel Biss at a community event in January. “But you’re starting to see it’s not just a tiny speck out there. We’ve been standing this up at the same time as Chicago and Cook County. We feel like we’re this ragtag team of people trying to do the same thing as these giant armies, and, frankly, we’re doing great.”

I wanted to assess the validity of Biss’ statement. Evanston residents needed to be at or below 250 percent of the federal poverty line and be between 18-24 years old, 62 and older or an undocumented community member just to apply for the program, and there were only 150 accepted. Evanston has a population of nearly 80,000, so universal isn’t a word in the same stratosphere as one that can accurately describe the pilot.

Not to say Evanston shouldn’t spend money on the program but is what they’re doing enough? Universal basic income reduces the poverty rate and income inequalities, eliminates the need for many other government supplemental programs and doesn’t reduce the motivation to work; it increases it. A guaranteed income program can only bring upside to those who receive it, so I intended to find that effect on one of the 150 who had received Evanston’s program and tell their story.

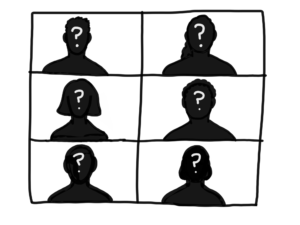

I couldn’t.

Not because there wasn’t anyone who had benefited from the program but because I couldn’t find them. As it turns out, that’s a good thing.

Evanston meant to protect recipients’ identities – remember, some were undocumented. But the Freedom of Information Act, a law that requires disclosure of previously unreleased or uncirculated information and passed in part so citizens could better understand the uses of their tax dollars, meant that there was only so much they could do.

Fortunately, Northwestern’s involvement and contribution to the fund that provided the payments, along with work from Lin, Mackevicius and Fuller, ensured the secureness of recipients’ information.

I value good journalism; it’s what I want to do after I finish school. When I came up with the idea for this article, I was trying to do good journalism.

All of that without thinking about why some things are private, to begin with. That zeal, while well-intentioned, can have dangerous consequences.

Who knows how the lives of the undocumented recipients would have changed if I had successfully procured the list of names to have applied for the program and made that information public? Who knows how the attitudes of friends and family would have changed if they had seen the names of a friend or family member on that list?

That’s no longer something that I want to know the answer to.

Making public that list wouldn’t have been holding anyone accountable, and it wouldn’t have been doing good journalism either. Good journalism doesn’t hurt people who don’t deserve it, and holding the Evanston City Council accountable would have been reporting on the research once it came out.

Releasing those names could have done untold damage to those names. Unintended, yes. Initially unforeseen, yes. But still damage. That’s not something I want to be responsible for.

I wanted to tell the stories of whatever names happened to be on that list. Part of me still does. But if they’re willing to share that information, they deserve the opportunity to tell their own story, not have it forced upon them by someone who hasn’t ever needed universal basic income and likely won’t.

It’s part of my job on The Evanstonian to amplify voices that want to be heard. Not fabricate them. Not pressure anyone uncomfortable with their story into sharing it. Amplify those voices.