One of my most prevalent memories as a young child was going to the afterschool program at the YMCA with a Kumon book in hand and doing the pages my parents had assigned for me that day. I took the bus, and because my elementary school — King Arts — released earlier than other schools at 2:45, I was always the first one there. The class space was quiet, and I always took my allotted snack portion and worked. As the other kids trickled in, boisterous and laughing, I sat at my table, head down, and continued my assigned pages. Maybe it was multiplication that day, or perhaps the addition of fractions. Whatever it was, it was sure to be above my grade level, with line after line of practice problems. Once I finished my pages, I joined the other kids as I waited to be picked up. The YMCA closed at 6:00, and I was always one of the last kids to leave. I didn’t realize it then, but as the Asian-American son of middle-class, immigrant parents, all of my key identities were already coming into play. Not only that, but my journey through education was being impacted as well, starting with the expressionless little face on the front of every Kumon book.

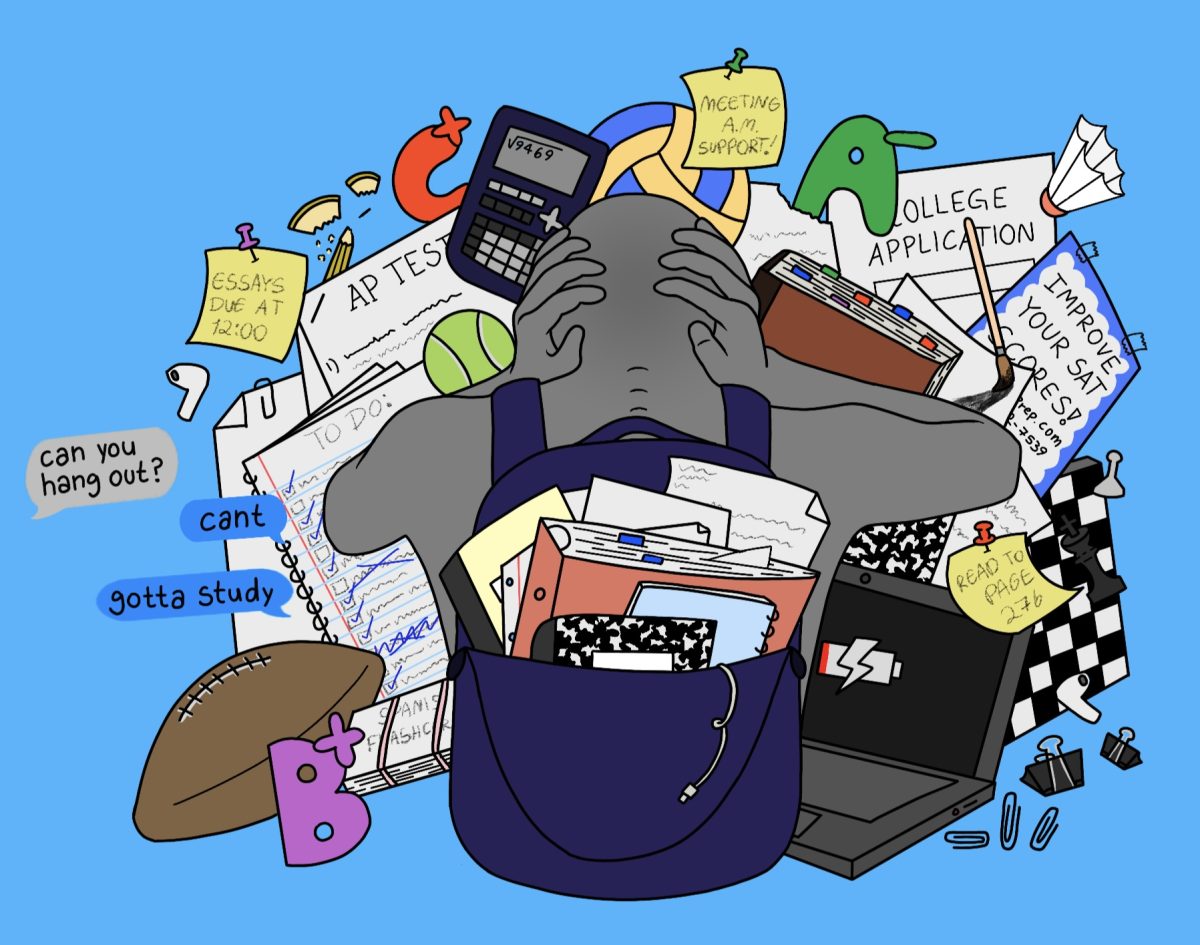

Something that has become clear to me now is that education in a school is simply about learning everything you need to know to get a satisfactory mark. I see the ways in which the school system, as well as my parents, has engineered me to be focused on the numbers, grades, and percentiles. Starting from that very first Kumon book, I interpret the decision to accelerate my learning outside of school by my parents to be an acknowledgment of how our society views education — that it isn’t truly about learning, not at its core. The goal of “education” in school is to uphold the capitalist nature of our society, which is evident in the way that institutions relegate students to numbers and stats, such as GPA and test scores, and pit them against each other to see who comes out on top. The way that I have experienced “education” throughout my life is intertwined greatly with both this fact and my Asian heritage.

Both of my parents immigrated to the United States from Taiwan in pursuit of a higher education. From the start, they weren’t here to complain about the system in place or to expose the inherent flaws that come with making students a number or a percentile. In fact, they came to the U.S. exactly for that reason. If a student accepts the way the system operates and takes it in stride by acquiring the best possible grades and test scores and being the top-ranked student in the class, then the pathway to employment, money and all parts of our capitalistic society becomes available. For Asian immigrants looking for this exact thing, the education system in place, with all of its testing and grading and ranking of students, became something acceptable — something beneficial.

So, it is no wonder that, as a child of Asian immigrant parents who believe in the U.S. education system, I began to take advantage of said system from an early age and immerse myself in the world of the important numbers: grades, test scores and percentiles. This fact has not only shaped my definition of education in America, but has also impacted my learning habits and what aspects of school I view as important.

Returning to the Kumon books, it became clear to me that school as a capitalistic system was already shaping my education. Yes, I was learning multiplication and addition of fractions, but for what reason? It seems silly, the idea of intentionally trying to get ahead of my fellow first-grade classmates, but to my Asian parents, it was necessary. How could I succeed in the system if I was just like everyone else? Just like my Kumon learning was tied to a specific purpose that would help me better game the system in the future, I now feel like my learning in school is tied to the same goal. The quantifying measures that are a result of my “education” all just serve to put me in a better position to make the most out of the way our society is structured. I am keenly aware of this fact, no matter how much the people around me such as my parents and teachers try to convince me otherwise.

Even in my most recent conversation with my father about my educational journey, he claimed that the purpose of accelerating my learning through Kumon books was to foster a love for learning in me. To learn not for anybody else, not for the sake of getting a good mark, but simply to cultivate a want to learn. Even now, my mother tells me to study not for the grades, but to truly become knowledgeable on the material. It is ironic how these same people are the ones who punish me for falling below an A, admonish me over test scores and compare me to other students who are doing more. If this encompasses education in America, then so be it. All I ask for is that the half-truths, the facade of “learning to learn,” are destroyed. My eyes have been opened throughout my educational journey; I am no longer the little child doing his Kumon while waiting for his parents, wondering why he has to do math while the other kids play.

I now know the truth, and what a relentless truth it is. I have never learned simply for the sake of learning, nor have I learned for myself. The curtains have been drawn back, and I have realized that my entire educational journey has only served to prepare me for the moments ahead — college, employment and the coveted “successful life.” In a way, shouldn’t I be thanking the American school system and my immigrant parents for revealing this truth to me? I’m not sure. What I do know is that I will continue to focus on the test scores and percentiles, and I will continue to study simply to achieve the top grade. After all, it is what I have been meticulously trained to do all my life.