It’s in the air. The return of final exams, or rather, “final experiences,” after their COVID hiatus has brought a noticeable sense of stress to the hallways. But it’s good. Well, sort of.

To be abundantly clear—the concept of a final assessment has merit. It pushes students to synthesize a semester’s worth of knowledge, hone time management skills and perform under pressure. These are all valuable skills that will serve students well in higher education and beyond, a known fact in all academic circles.

“Although teachers should not ignore or discount student preferences across the board, there is the larger issue of which testing procedures best promote deep learning and lasting retention of course content,” said a teaching services article published by the University of Illinois. “The evidence on the side of cumulative exams and finals is pretty much overwhelming, and those empirical results should not come as a surprise. An exam with questions on current and previous content encourages continued interaction with course material, and the more students deal with the content, the better the chances they will remember it.”

Similar arguments were made by those in administration responsible for bringing back the “finals experience” at ETHS.

“It’s a reset for the district. All the alums, and people in general, say it’s good prep for those who are going to go to college and other [post-high school options], because that’s what folks will be doing out in the real world,” said Superintendent Marcus Campbell.

That’s all great, but there is a problem. The current “one-size-fits-all” approach to finals week is where the logic falters. Right now, teachers are expected to give some sort of in-person examination to every student during finals week, meaning students have to show up to every class—even if there is no real test to take.

That is especially true for gym classes, but some students are able to see the upside.

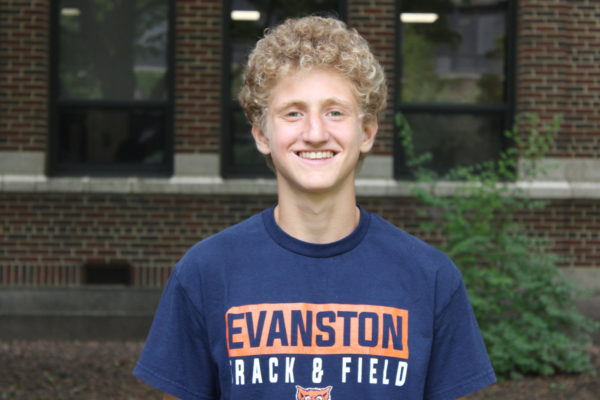

“In my gym class we’re taking the final this week,” said senior Miles Sato. “Although we still have to come in during finals week, it’ll be one less final to have to study for next week.”

Now, there is final exam customization that happens. In photography classes, students will be making portfolios; in performing arts classes, students will do just that—perform on stage. However, that customization should also carry over to the administration’s logistical approach to finals week.

Where ETHS needs to improve is the structuring of the week itself. In classes where portfolios, projects or non-exam demonstrations are the best way to measure student success in a cumulative way, students should not have to waste time by coming to sit in class during finals week. That time would be much better spent preparing for other finals—ones where a sit-down exam is the best way to evaluate students. Final exams are a real, important academic tool, and their effectiveness shouldn’t be jeopardized by making students spend pointless hours in exam rooms.

Luckily, ETHS administrators are cognizant of the issue.

“We have to revisit [the structure of finals week], because that question has come up over and over and over again, and we haven’t had to answer for years because we only just brought back finals,” said Campbell. “Now [finals are] back again, and I think it really begs the conversation with the administration.”

So what should ETHS do in future years? For one, keep administering some kind of final exam—that’s clear. But instead of forcing a logistic agenda on all classes, let teachers determine if students need to be in attendance during finals week, based on the nature of the final exam. It seems like the administration is progressing in that manner—let’s keep it that way. Let’s embrace the return of final experiences, but let’s also embrace the opportunity to make them more relevant and effective.