“Every year, we take a moment to honor and recognize all the academic excellence that students have grown into and maintained after seven semesters of high school,” said Assistant Superintendent and Principal Taya Kinzie. “Please stand, Class of 2023, when I recognize your achievement.”

The first called to stand were those students who graduated with distinction (weighted GPA of 3.5 to 3.749). Four, maybe five, students stood. Next up were students with high distinction (weighted GPA of 3.75 to 3.99). About 25 students stood. Finally, those graduating with highest distinction (weighted GPA 4.0 or higher) were called. Almost the entire graduating student body stood up.

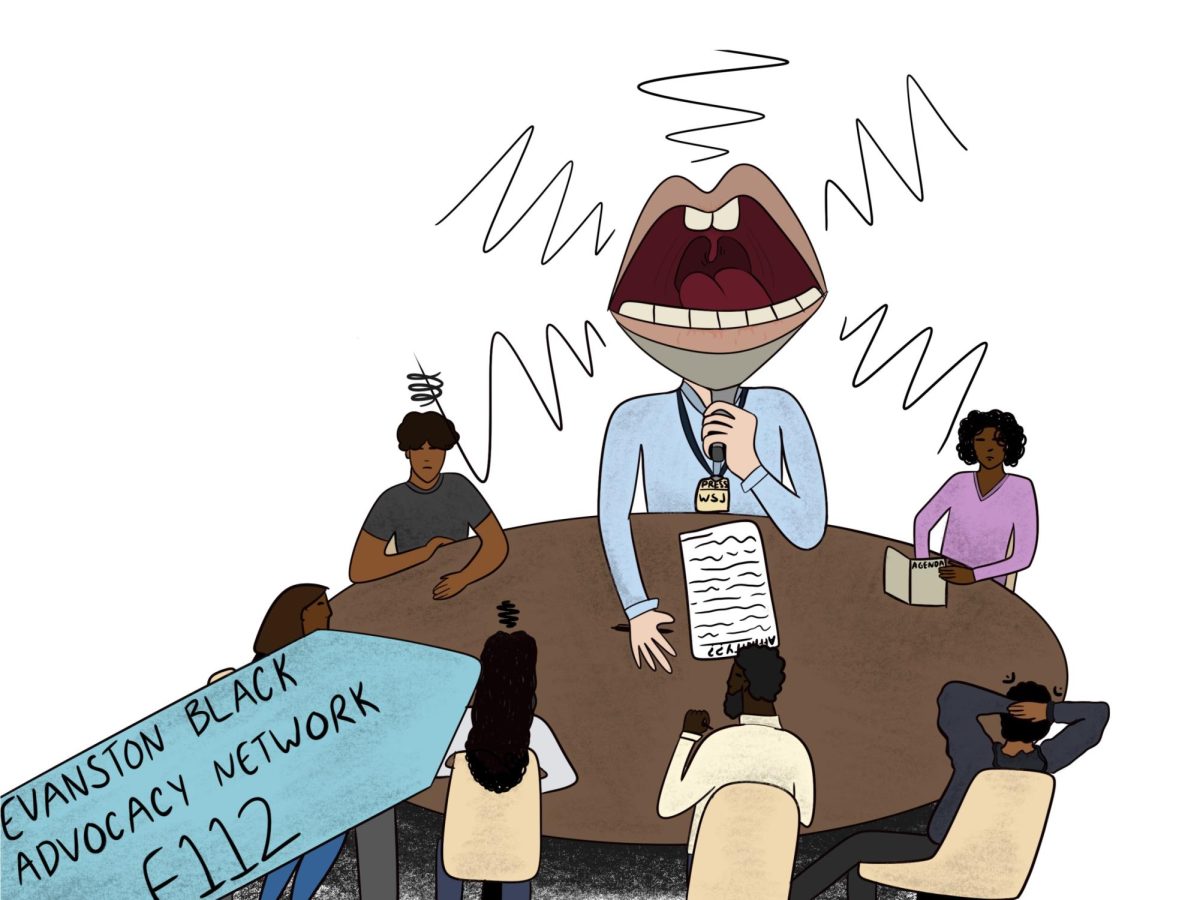

Merriam-Webster defines grade inflation as “A rise in the average grade assigned to students.” When the vast majority of a graduating class leaves high school having earned the highest distinction for their grades, it makes one wonder if that distinction is so high after all, and, more broadly, if grade inflation is at play. While the scene described above was a very specific moment from one graduation (2023), it is representative of an overall trend in education — students walk into each class expecting to get an A, and teachers are willing to oblige. It is grade inflation at its finest, and it is spreading across high schools and universities across the country. ETHS is not an exception.

The issue is easy enough to diagnose, but finding a viable solution is much harder. Grade inflation stems from several factors, some of which are ingrained in the very nature of the feedback-oriented education system we cherish.

For new teachers, that feedback, or rather the potential for career-harming negative feedback, can directly lead to inflated grades. As one teacher described, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, teachers never receive angry letters about good grades they might give a student, but for bad grades, parents tend to get involved. At ETHS, it takes two-to-three years of consecutive teaching, depending on administration rating, to receive tenure, and while it is unlikely that anybody would be let go for giving a bad grade or two, an excess of negative feedback from parents certainly doesn’t help in the pursuit of tenure.

There’s another problem that can’t easily be solved — the fact that many teachers, each with their own teaching style and ways of implementing the grading system, can teach the same class that is listed in the same way on a student’s transcript. This creates a situation of false standardization, where students expect to receive the same grades for the same amount of effort, no matter the teacher. Somewhat obviously, that kind of standardization is almost impossible to guarantee with ETHS’ current grading system, and teachers who teach the same class invariably get categorized as the ‘easy’ or ‘hard’ teacher for a certain subject. In that system, the teacher who grades the most leniently will always set the standard, and other teachers will either have to lower their grading standards or risk becoming the teacher that all students dread — a reputation that, understandably, is not ideal for most.

But why should we even care about grade inflation? Why should we have a problem with students walking out of every semester with the satisfactory feeling of getting all A’s? The answer is simple — honesty. Grades are supposed to be objective measures of a student’s progress, and the more they fall victim to inflation, the less objective they become. While that might not seem like a huge issue at face value (besides the slight moral dilemma) it becomes quite important when looking at college applications.

If teachers hand out A’s to students, it becomes very difficult to distinguish oneself academically, leading to pools of students that apply to colleges with the exact same GPA — a perfect 4.0. Now, the job of a college admission officer becomes much more difficult. They obviously can’t let every applicant in, but they can’t sort them by academic merit, since grade-inflated transcripts are essentially identical. This leaves them with two options: distinguishing by standardized test scores or distinguishing solely by extracurricular activities. Both are not ideal. Admissions based on SAT or ACT scores benefit those students who are good test takers, but they say little about a student’s capacity to sustain prolonged effort throughout an entire semester of coursework, which is what college academics are based on. Admissions based on extracurricular activities can work, but often fall victim to chance. What metric can determine if four years of volleyball or four years of student government are better indicators of a student’s future success? The answer is that there usually isn’t one. A tougher grading system would result in a more significant grade distribution, ultimately helping college admissions officers make informed decisions based on students’ true potential for academic success.

So what can be done to stop grade inflation? As one might already be able to tell, there isn’t a single easy solution. Teachers will always have to face backlash from students and parents alike about grading decisions, and there will always be teachers in more precarious moments in their careers, where they’re more hesitant to come into conflict with those around them. One viable solution, however, can be found by looking at College Board, the nonprofit that runs the college-level Advanced Placement courses.

At the end of every year of AP instruction, students have the opportunity to take an AP Exam. These exams come in different forms: some are essay-dependent, some are like long math tests, and some are project or portfolio-based. The unifying factor, however, is that these tests are standardized, and therefore hold all students equally responsible for the material they were supposed to have learned over the course of the academic year. No matter a teacher’s teaching style, they are successful if they prepare students for the exam, and, ideally, are held accountable for the scores that their students produce at the end of the year. This idea, that classes can be taught in any manner but, ultimately, have to teach students material that everyone is responsible for knowing is a good one, and can be applied to not only AP courses. What if, in all classes at ETHS, standardized unit tests were developed and administered with regularity, and were the main determinants of grades? Then, regardless of the teacher or their teaching style, students would be graded in a fair manner, and teachers themselves would be held accountable for ensuring they give rigorous enough coursework to prepare students for those exams. In that scenario, an A would truly be the same A that another student received, and the excuses of ‘I got an A because I had the easy teacher’ or conversely ‘I got the C in the hard teacher’s class’ would be untrue.

That idea may be harder to implement than it seems, but it would lead to fairer grading practices. Luckily, ETHS is already taking some steps in that direction, especially with the reimplementation of final exams this year. That decision, however, comes with its own issues, because until those exams count for more than 10 percent of a student’s semester grade, they are unlikely to provide the standardization that is needed to fix grade inflation. Still, it might be the baby step we need to get the ball rolling towards more honest grades.

When talking about grade inflation, it is easy to criticize it from a zoomed-out perspective. As seniors in high school, we certainly have been thankful for easy grading at times, especially during our junior year when every point in the gradebook felt worth fighting for. These critiques are not to express that students who get good grades don’t deserve them, or that we would be happier with lower grades ourselves, but rather to point out some issues with the current grading system as it is. For lasting change to happen, it must happen to all students at ETHS in the most objective way possible. Students shouldn’t receive bad grades just to learn a lesson, but they also shouldn’t receive perfect grades just for attending class most days. In the long run, a single B will not impact a student very much. A grade that is truly reflective of the work they put into a subject, and the lessons they learn about themselves as they navigate a challenging class, will.