In 1994, as a young Dino Robinson entered the Evanston History Center and walked into the archival area, he had no doubt that there would be plenty of reference information for his article on Black history in Evanston. After all, the Black population was around 16,000 at the time, and his request had been broad, “anything on Black history in Evanston.” He was in for a surprise.

“Out of all the records, the archivists pulled out only three file folders, labeled ‘color.’ And that’s when I decided something needed to be done,” said Robinson.

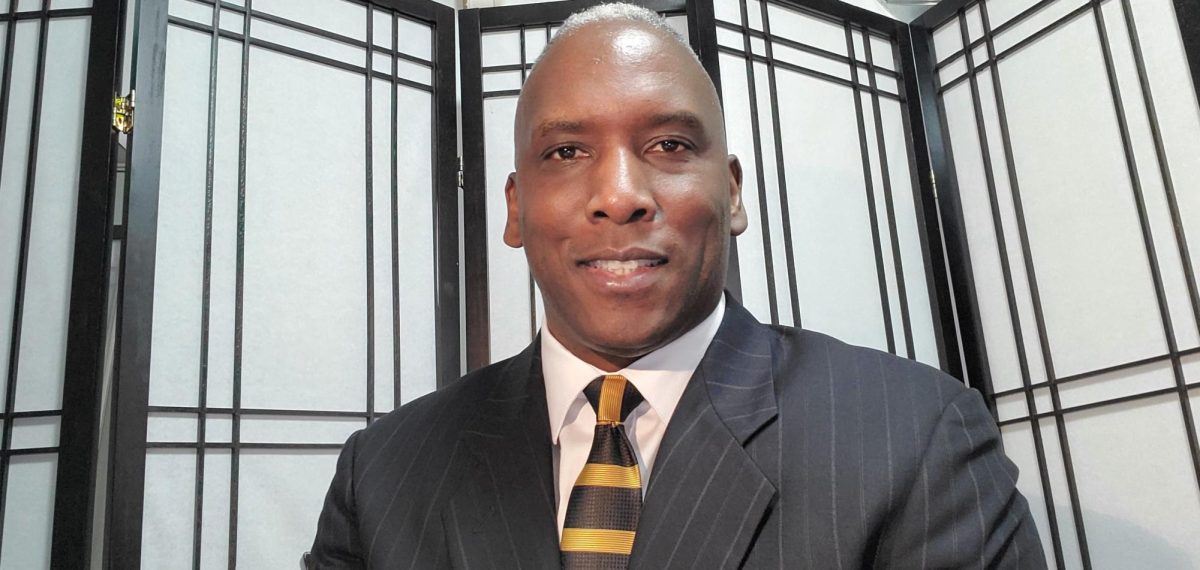

30 years later, Robinson is Evanston’s leading historian and founder of the Shorefront Legacy Center, an institution dedicated to preserving Evanston’s Black history. Serving as a key reference to Robin Rue Simmons and the push for reparations in Evanston, Robinson has also worked nationally with institutions such as the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington D.C.

“I found that there was a vast gap in the historical narratives of Black residents in the suburbs of Chicago, and so I set out to fill that gap,” said Robinson.

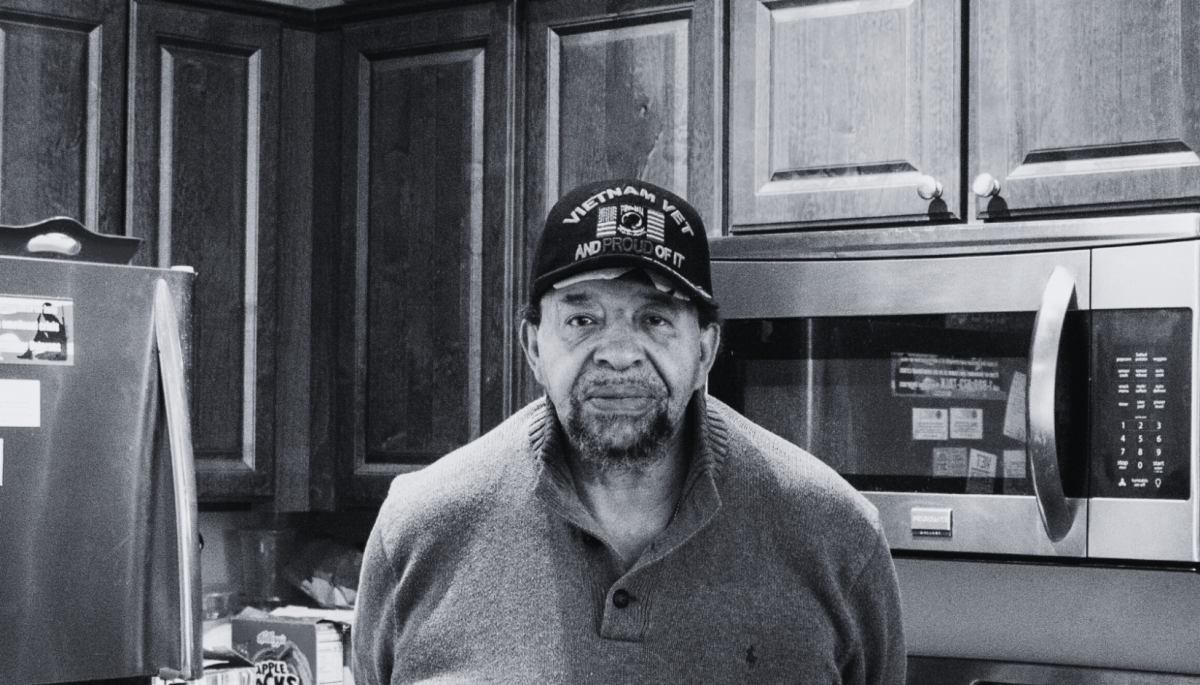

For all the work that he has done in Evanston, however, the first three years of his life were mainly spent thousands of miles away, on an army base in Italy. Born Morris Robinson Jr., in Chicago, he flew to Italy at three months old with his mother and father while his father served in the Vietnam War. When the soldiers were decommissioned, Robinson moved back to Chicago. His moniker in Italy, Dino, roughly the equivalent of ‘junior,’ stuck, serving as his nickname throughout the rest of his life.

Soon after, Robinson and his family moved to Glenview, just before he entered kindergarten. At the time, he was one of 24 Black people living in the town.

“Going into my elementary school, I was the one integrating it,” Robinson said.

As the only Black student in his school, Robinson experienced, and still remembers, numerous incidents of racial discrimination, starting as early as Kindergarten.

“Within the first couple of weeks at the school, a classmate, as we’re going through play time, walked up to me and basically said, [racial slur] are not allowed to play with toys, proceeding to kick me in my stomach,” said Robinson. “And I was a few feet away from the teacher and she heard him but she did nothing about it.”

Throughout the remainder of his childhood schooling experience, Robinson continually faced race-based obstacles. Although he had many encouraging, formative teachers, he also had multiple who tried to convince his parents that he was incapable of learning.

“Navigating my early life, in addition to all the normal childhood challenges, I also had that extra level of race [discrimination],” said Robinson.

Early experiences with history curricula proved unfruitful for him as well, often skipping over swaths of Black history and exclusively celebrating white historical figures. However, spending time with his family and listening to their stories fueled Robinson’s history interests.

“When we went to family reunions, I would act like a fly on a wall listening to the adult stories of growing up,” said Robinson. “On my father’s side, coming from Arkansas to Chicago, on my mother’s side from South Carolina to Chicago; and hearing my grandparents, aunts, uncles, great aunts and great uncles speak about life before and how things had changed or stayed the same.”

After one year of middle school in Glenview, Robinson moved to Evanston, attending Nichols and then Evanston Township High School, where he benefited from the more diverse community. While some challenges remained, he was able to take stimulating courses and explore his interests.

After doing an internship in advertising, Robinson developed an appreciation for the industry. That, coupled with his longtime passion for history, defined his two areas of focus in college. While attending Loyola University Chicago, he took all the history courses he could, eventually landing on one entitled ‘Early Christianity in Africa.’ Upon arriving in class, and finding a white professor standing among the all-Black class, Robinson questioned his decision to take the course. However, it proved to be a formative experience in his young adult life, teaching him valuable skills about research that would steer his future efforts in Evanston.

“We were going on field trips to libraries, going into the archives to look into firsthand materials to critique what’s already written in the history books, saying, ‘Is this actually accurate and who’s controlling the narrative?’ [The class] taught us some valuable lessons in research, and that really pushed me to think about how I apply research to anything I do,” said Robinson. “That helped guide me with the development of Shorefront.”

After graduating college, Robinson worked briefly as an art director at several advertising firms in Chicago, eventually moving to Evanston and starting his own business, Robinson Design. He specialized in logo development, publications and exhibit design. Soon after, he started talking with the editor of a now-defunct newspaper called the Evanston Clarion, which ran from 1994 to 1999. After much encouragement, he persuaded Robinson to write an article about Evanston’s Black history, prompting his discouraging visit to the Evanston History Center.

In the year following his unsuccessful 1994 experience of discovering records of Black history on the North Shore, Robinson began to create his own archive. Starting mainly with oral histories, he slowly built up his historical repertoire, following branches of information that he gathered in conversations with residents.

“I just listened—and picked up on bits of information, timelines, locations and facts—then I tried to go out and look for the paperwork that supported that,” said Robinson.

Bit by bit, piece by piece, Robinson assembled his collection.

“As I was collecting this information and organizing them, it grew from a few file folders to a couple of boxes to now over 750 linear feet of archival material,” said Robinson. “I created an archive from the ground up.”

Collecting all the information to sustain and develop his archive was no simple task. Although in 1995 Robinson was a longtime Evanston resident, he spent most of his childhood elsewhere, a fact that hampered some of his initial efforts.

“The big thing was earning respect and trust in the community, because of the nuance of social politics,” said Robinson. “Starting Shorefront 25 years ago, I was considered a newcomer to Evanston. There was a very specific, cultural dynamic with that, and I realized that I had to tread lightly in how I approached learning about history.”

A point that he often reinforced to encourage participation in his work was the interconnectedness of everyone’s personal history.

“We all have a sense of knowing our particular histories according to our own timeline,” said Robsinson. “But collectively, we don’t know enough to really travel back in time to the beginning.”

Slowly but surely, as he interviewed more and more residents, he earned the respect of many community members, who supported his work and referred him to possible sources of additional information. As Robinson built up his archive, he faced another challenge: those who didn’t trust in the power of oral histories.

“Oral histories and oral traditions were not considered serious work, it was anecdotal at best,” said Robinson. “And I wanted to start changing that narrative to show people that oral histories were more relevant than they thought. To do that, I had to challenge institutions that were established that believed that they should be the gatekeepers of all things history and determine what was important and what wasn’t important.”

Throughout all his work, Robinson has focused on that theme, the removal of ‘history gatekeepers.’ In many situations, he described, an institution will go into a community, take all the resources and information and then hide it behind their academic walls, creating the need for independent, community based record-keeping organizations.

“The community is left with no resources and have to ask permission to see their own history inside an institution that they may or may not be able to get into,” said Robinson. “I wanted to change that narrative.”

Robinson officially incorporated Shorefront in 2002, with a three-faceted mission: to collect, preserve and educate people about the Black history of Chicago’s suburban North Shore.

To meet the public education objective, Shorefront began publishing a printed journal, which ran four issues a year from 1999 to 2010. After becoming too costly to maintain, the format changed to an online journal, which proved to generate much more public engagement and readership, even permeating to governmental figures.

“Last year, at this time, we were presenting to the City Council, and they all made comments about how much they’d learned through Shorefront and how they incorporated that into their work,” said Robinson. “And I sat back and said, ‘Wow, we’ve reached our vision, making local history common knowledge.’”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

With thousands of historical records at his fingertips, Robinson was the ideal partner in the fight for reparations in Evanston. But before working directly on the issue, he was temporarily hired by the Equity and Empowerment Commission, a group formed by the City to address racial equity and justice in Evanston. As part of his project, Robinson made a three panel exhibit entitled ‘Redlining Evanston,’ which covered the housing issues that Black residents faced from 1860 to 2000. Those panels, in combination with a broader exhibit covering redlining in the entire United States, served as an important reminder of Evanston’s history of housing discrimination.

“[The exhibit] really put forward the issues concerning Evanston and it really slapped everyone in the face, hard, saying, ‘we were implicit in doing the same thing the rest of the nation was doing,’” said Robinson.

Following the exhibit, and the subsequent reparations efforts led by then-Ninth Ward Alderwomen Robin Rue Simmons, City officials came to Shorefront to do preliminary research on the topic of historical discrimination against Black residents by the City of Evanston. However, after the initial nine page report, City staff still needed more information.

Upon consulting Rue Simmons and other leaders, they subsequently hired Shorefront, and Robinson became the project lead in creating a report titled ‘Evanston Policies and Practices Directly Affecting the African-American Community.’

“I knew, as well as the City Council, that he would be the person to prepare the report,” said Rue Simmons.

Robinson collaborated with Jenny Thomson, Director of Education at the Evanston History Center, to create an inceptive 20-page report in 10 days, which grew to 80 pages soon after. As Rue Simmons and other reparations leaders gathered community input and determined the first phase of their plan, housing initiatives, the legality of it all came into question.

“That’s where my report came into handy. It not only talked about the legal arm of housing restrictions, but also the culture of discrimination and Jim Crow that the City of Evanston participated in, including housing, location, education, health, all these factors that play into it,” said Robinson.

Another outcome of the report was the designation of a time period of harm, in which Black residents who lived in the city from 1919 to 1969 qualified for reparations.

When looking at the broader reparations movement in Evanston, Rue Simmons noted the importance of Robinson’s timely contributions.

“It began with leaders like Dino Robinson playing a very, very key role in accelerating our report to build the case for reparations,” said Rue Simmons. “Without Dino’s responsiveness, I think we would have been much further behind in the process.”

The passage of Resolution 126-R-19 by the City Council in 2019 marked a significant milestone in the push for reparations, including the development of a reparations committee, chaired by Rue Simmons and an initial reparations fund of $10 million. However, some residents were not satisfied with the result, resulting in vocal opposition to the efforts of Rue Simmons, Robinson and other public servants.

“Nobody predicted that the City of Evanston would actually put money where the mouth was, and when it did happen, they said ‘it’s not enough,’” said Robinson. “You can choose to sit on the sidelines and complain that it’s not enough, or you can come to the table acknowledging that it’s not enough and find ways to make it more. I choose to come to the table and help make it more.”

Since the initiation of the reparations fund, the original $10 million has grown to $20 million. Robinson himself doesn’t even qualify for the conditions surrounding reparations, as his family came to Evanston in 1980, yet, with an effort as trailblazing as it was, he recognized that the community has to start somewhere. To all those who want immediate change, he encourages them to have patience.

“We’re talking about 400 years of slavery, 100 years of Jim Crow and 60 plus years of police brutality and other discriminatory practices,” said Robinson. “You cannot change that overnight with one payment.”

Another important consideration for Robinson is the potential for reparations at multiple governmental levels. Just like one pays city, state and federal taxes, he believes that there should be city, state and federal reparations, each individually addressing their unique harm on the Black community.

“What we’re focused on here on localized reparations is what the City of Evanston specifically did to push the [reparations initiative] forward,” said Robinson. “And it does not negate any activity the federal government or the state government does to help mediate in the form of reparations.”

To that end, local reparations leaders like Rue Simmons have been working on a national level with members of Congress to help pass the proposed bill HR-40, that would establish a committee to study Black history and the potentialities of national reparations.

Throughout the entire process of establishing—and maintaining—reparations efforts in Evanston, Rue Simmons believes that Robinson’s work has been invaluable.

“Although Dino’s not even eligible for reparations, you would not know the difference. He really nurtured and supported this work as if his own family were harmed, because I think many of us in the global Black community recognize the harm that has been inflicted on other community members,” said Rue Simmons. “Dino has been a giant in the work in Evanston, and has been an inspiration to the many other communities that are modeling their legislation after Evanston.”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

As Robinson continued his work with Shorefront, he developed relationships with other historical institutions throughout the North Shore, many of whom wanted the guidance of a community member as they continued their work. Northwestern University was one of those institutions, and over the years they have become a close partner of Robinson.

Throughout much of his early years at Shorefront, he continued his work at Robinson Design, splitting working hours between the two. As time went on, however, Robinson started devoting much more time to his archival work, relying on a few select clients to sustain his advertising business.

In 2008, he was hired by the Northwestern University Press, the publishing branch of the institution. The job, while giving him a more structured work environment, still allowed him to devote much of his time to his work at Shorefront, mainly after work and on weekends.

In 2023 Shorefront hired its first paid Executive Director, Laurice Bell, taking on the position after Robinson stepped down in early 2023. That, coupled with a 50 percent turnover of the board, helped the organization refocus on some goals, such as raising money and the creation of an endowment.

“I’m taking pleasure in stepping back from it and I’m able to focus now on projects that I put on the backburner,” said Robinson.

Part of the switch involved Robinson relocating to Georgia, where he now spends the majority of the year. He continues to work for the Northwestern University Press, remotely, and comes back to Evanston for about two months a year to work on larger projects.

Throughout his long career in the city, Robinson’s singular mission has been realized, and Shorefront continues to serve as a place where local history is documented, preserved and accessed. In addition to his contributions to Shorefront, his importance as a community member has not gone unnoticed. In central Evanston, residents can drive down “Morris ‘Dino’ Robinson Jr. Way.”

“Other institutions used to write off Shorefront saying ‘Oh, it’s just a fly-by-night thing and it’ll go away,’” said Robinson. “25 years later, we haven’t gone away. Now we’ve become more of a major player where our opinions are valued, and our goals are replicated.”