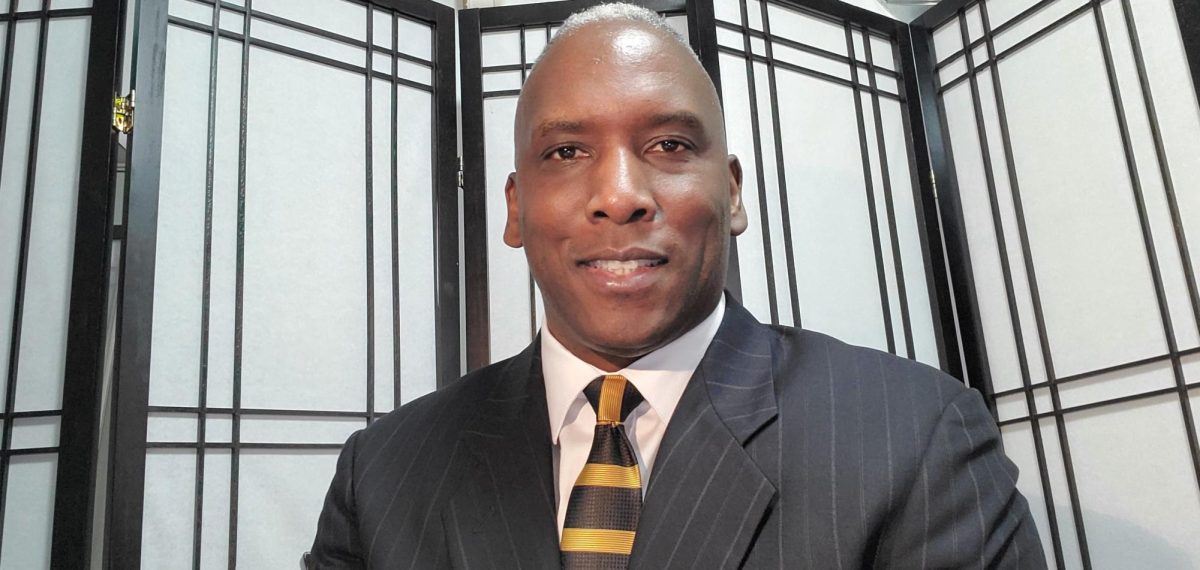

After his mother-in-law became sick in 2011, Kevin Brown traveled back and forth between Sacramento and his wife’s hometown of Evanston, searching for a job position in the Chicago suburb. Brown’s father-in-law, Phil Logan, was Evanston’s chief of police from 1957-1987. The bond that tied the Logans to Evanston was instilled in Brown, who fell in love with the suburb.

“It’s been really beautiful because a lot of people think that I actually grew up in Evanston, but really I just fell in love with Evanston after I married into the Logan family,” Brown laughed. “I just think Evanston is one of the best places on Earth to live. I really believe that.”

Brown first came to Evanston in 1981, where he was recruited by Northwestern football head coach Dennis Green. Brown played for the Wildcats from 1981-1985, before being drafted by the Los Angeles Rams in the eleventh round of the 1985 NFL Draft. However, his football career was cut short after just a six-month stint on the practice squad.

As his football career came to a close, Brown worked in higher education at both Penn State University and Pomona College, where he was the dean of admissions at the latter. After a couple of years of work, Brown headed to St. Louis to attend law school at Washington University, where he graduated in 1992 and worked as an assistant city attorney in St. Louis.

“I can vividly remember as an eight-year-old wanting to be a lawyer after growing up watching Perry Mason,” Brown said. “I told myself to pursue that as a dream. But what I learned through that experience was that the law pretty much touches every single aspect of life. Both of my parents were civil rights activists and that was ingrained in me to always fight for justice, particularly for black people and others who are disenfranchised.”

Following a quick return to higher education, Brown moved to Sacramento, California to work alongside former NBA player and mayor Kevin Johnson in setting up St. Hope Academy, a charter school, where Brown eventually worked as the headmaster for a year. From there, Brown worked as a compliance officer for the Sacramento City Unified School District for eight years and as a policy consultant for the California School Board Association from 2007-2012.

When Brown traveled back to Evanston, he applied for the Evanston Youth and Young Adult Program managerial position. When he received that role, he was promoted to Community Service Manager, where he handled the Youth and Young Adult Division for the city. Working in that role from 2012 to 2019, Evanston saw a 220% decline in the arrests of people aged 16 to 24.

“We had quite a bit of success in the program that I ran,” Brown stated. “We provided thousands of jobs for young Evanstonians throughout an eight-year period and it had a major impact on the reduction of violence in our community. It was great because we received national and local recognition for that particular program.”

As Community Service manager, Brown worked directly with former mayor Elizabeth Tisdahl on a program that could positively impact Evanston youth, primarily youth of color, who were living below the poverty line.

“In my time working for the city, I discovered that around 40 percent of students were on free and reduced lunch, which signals that they come from families in poverty. So when I met [Mayor Tisdahl], she supported me 100 percent to come up with some ideas. We decided that working on both employment issues as well as housing issues was one way to go about more equity in our community to help families in poverty.”

In addition to helping the Mayor’s Summer Youth Employment Program function, Brown added a component to the program that employed 150 teens full-time throughout the year.

“What we saw with this program was tens of thousands of dollars being poured back into these families and to the young people of Evanston,” Brown said. “That created more family stability for those families and improved their lives as a result. That was essentially a government equity [program].”

But suddenly, Brown was terminated from his role in the city in November of 2019 for parking ticket allegations. Lawrence Hemingway, the city’s director of Parks, Recreation, and Community Services, found that Brown had breached a number of city rules surrounding negligence and theft that all tied back to parking tickets that Brown’s team received while parking in the Evanston Civic Center parking lot. When paying for the parking tickets, Brown claimed that he was told to use his city credit card to finance the violations. That’s when Brown believed the entire case became blown out of proportion.

“I think that there was both discrimination and retaliation by the city against me,” Brown stated. “It’s for reasons that I think someone in the city wasn’t happy with the way that I may have spoken to somebody else and they retaliated by using this ticket payment to say that I was violating the credit card policy. Instead of coming up to me about this, they decided to terminate me based on that policy.”

When Evanston introduced its reparations program in 2019, Brown was newly terminated from his role in the city. However, as an Evanston resident weaved into numerous aspects of the city, getting reparations right for Evanston meant everything to him. But as the details of the program unraveled, Brown became increasingly concerned that the reparations plan didn’t address what former Fifth Ward Council Member Robin Rue-Simmons had initially proposed.

“When the city decided to develop a reparations program through Robin Rue-Simmons, I was excited about that,” Brown said. “She’s on record saying that it wouldn’t be a housing program. But somewhere in the planning process, she backtracked and turned it into a housing program. I saw that as more of a social equity program that didn’t really capture the spirit of what true reparations would be.”

That’s when Brown started Evanston Rejects Racist Reparations, a group that isn’t necessarily opposed to providing financial benefits to Black Evanstonians, but rather against labeling the housing program as reparations. While the group primarily serves as a social media presence on Facebook informing the community about the potential harms of the program, Brown says the team has expanded efforts by collaborating with similar grassroots groups across the country.

“We’ve hosted informational events online where people could discuss these issues and talk about other ways they can approach their local communities to support the idea of national reparations. We also have around 800 followers in our city who get important information from our page.”

Not only would Brown’s ideal reparations program be on a national scale, but he also called on Evanston to rename their initiative.

“[Evanston] could call the current program a social equity program or social justice program that is leading to the idea of reparations. It’s not reparations. That’s a huge misnomer,” Brown emphasized. “I think the majority of people in this country are fair-minded, believe in their neighbors, and want to see unity and peace and justice. If I were elected to City Council– and I’m not running– I’d want to rename the program and educate our communities on what real reparations [look like].”

Brown and Evanston Rejects Racist Reparations has called on local leaders to step up and not back down from the retaliation of the community against Evanston’s reparations plan.

“We need leaders like the people who started Evanston Rejects Racist Reparations. There has to be more leadership that arises from the black community in city government,” Brown stated. “Those people are mainly appointed to their positions by members of the white community and they aren’t representative of the black community as a whole in their positions on issues. That’s the way I see the current system [in Evanston].”

In addition to managing the group, Brown currently works as the Senior Director of External Affairs and Community Partnerships for the Safer Foundation, a Chicago nonprofit serving individuals impacted by the criminal justice system by helping those individuals secure jobs and housing. Similar to his work as Community Services manager, Brown and the Safer Foundation engage in workforce development and training, as well as behavioral health and wellness for individuals seeking a second chance. Brown’s ultimate hope is that his work for the Safer Foundation and with Evanston Rejects Racist Reparations can inspire people to not only support his cause but publicly voice their opinions.

“People support our work. People support our narrative. But they’re afraid to voice their opinion,” Brown stated. “That mentality is prevalent in our community, and I hope those residents can stand up for themselves.”