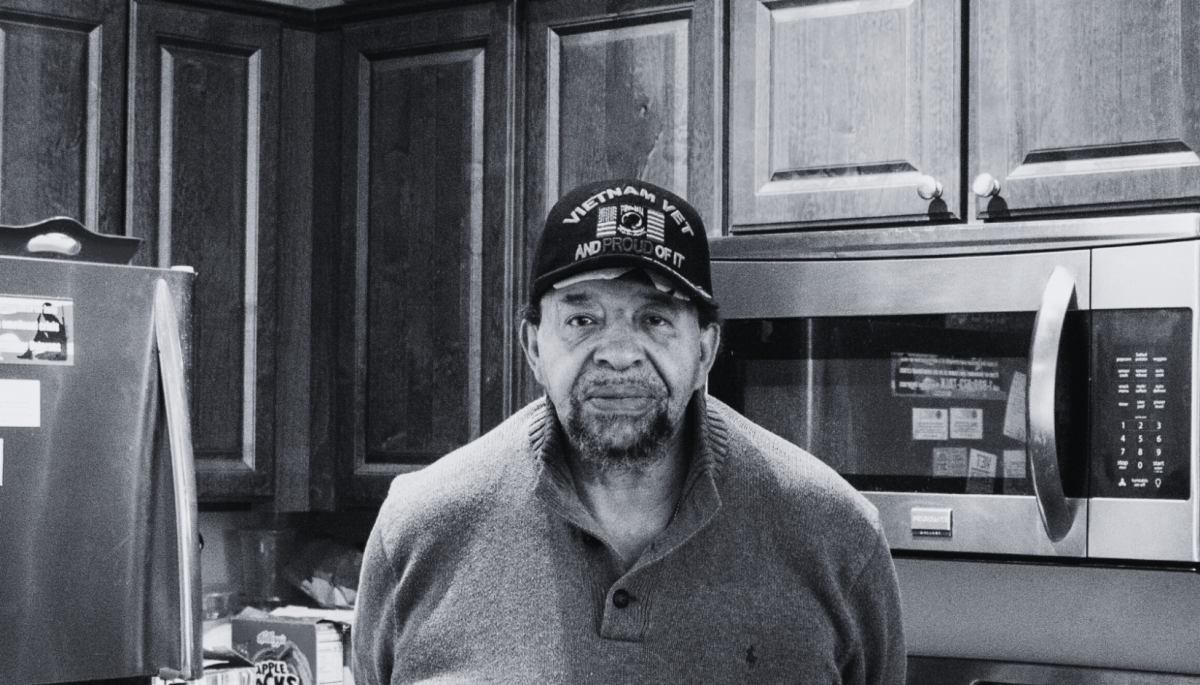

Kenneth “Dos” Wideman’s quaint one bedroom apartment on Ridge Avenue—nestled among some of the city’s most beloved restaurants—has everything he could want in a home. Within the apartment’s four walls, sounds of intermittent city traffic waft throughout, alongside the gentle humming of the washing machine, the subtle creaking of his favorite faux-leather rocking chair, and the sound of the television, which is turned to the local news channel.

On Jan. 13, 2022, 78-year-old Kenneth and his younger sister Sheila were selected as two of the first 16 beneficiaries of Evanston’s Local Reparations Restorative Housing Program. The program, in its initial form, issued payments of $25,000 for housing benefits like mortgage assistance or renovations. After their names were randomly drawn, the sibling pair was given the option to purchase property of their own—and become first-time homeowners—however neither were interested in leaving their respective apartments or taking on a mortgage. Perhaps unknowingly, the Wideman’s unveiled a shortcoming of Evanston’s reparations initiative: the absence of an option for direct cash payout.

“[Both] my sister and I live in apartments, but [the city] wanted [us] to use the money to fix up or repair a house,” Kenneth said.

In Mar. 2022, Kenneth was informed by the city that he and his sister had one-year to spend their reparations grant, and as the expiration date neared, Kenneth took matters into his own hands, vocalizing his sentiments in public comment at the Feb. 2, 2023 Reparations Committee meeting.

“It had been almost a year and we would have been knocked out from [receiving] reparations. So I went and talked to the city and I told them how I felt. We didn’t want to be taken off the list,” Kenneth affirmed.

On Mar. 27, 2023, two years after the city guaranteed funding for reparations for a number of its Black residents, the initiative broadened its scope—with the Wideman’s story as a guiding light—adding a real estate transfer tax to its revenue stream and allowing for cash payouts.

“The committee, along with the City of Evanston, revised the [plan] and [ultimately] allowed my sister and I to receive cash payments,” Kenneth said.

Kenneth had the opportunity to see Evanston’s project go from conception to completion.

“I went to one of the first meetings that the City of Evanston held over at First Church of God on the corner of Ashlyn and Simpson, when they came together to bring up reparations,” Kenneth said. “[Later on], my sister and I went to the Evanston Public Library to put in an application. The city [eventually] chose 16 people. My sister was number eight, and I was number nine,” Kenneth said. We are some of the lucky ones.”

As the city proposes their plan for the next round of reparation disbursements, Kenneth hopes to see Evanston embrace a more comprehensive reparations program that will help future recipients prosper.

“I look at it like this. The [recipients] that come after me, I want them to get more than what I got. They earned it. I want people to be able to do more and get more than what I received,” he said. “$25,000 is just a drop in the bucket.”

Across the nation, several cities have picked up the pace on reparations efforts. Kenneth believes that Evanston, as the first municipality to create and enact a government-funded reparations program, and being much further along in the process of disbursing funds, will be a model.

“Word has gotten around to a lot of cities, and I think they will use [Evanston’s] example to be able to get reparations in their cities. I wish the other cities well,” he shared. “I want people to [receive] reparations.”

Kenneth and Sheila grew up in the heart of Evanston’s Fifth Ward—once historically segregated—and while Evanston is all they remember, the third generation Evanstonians’ roots can be traced back to South Carolina.

“When [my grandmother and her family] first came to Evanston [during the Great Migration], they lived on the north side, but they ended up [moving] to the Fifth Ward,” Kenneth said. “[My family] lived in a house on the corner of Simpson and Dodge from 1945—when I was born—until 1991. The house we lived in [slept] about 14 people and I lived in one bedroom with my mother, my sister and my grandmother. I come from a matriarchal family; nothing but women.”

Despite having very little, Kenneth recalls a fulfilling childhood.

“When I was growing up, I thought I was rich. My mother did day work—domestic work—and she made a living for us,” he shared.

For Kenneth, basketball served as a cornerstone of his upbringing, and carried with him into adulthood, in his role as a coach with the Fellowship of Afro-American Men (FAAM) Youth Basketball League for over three decades.

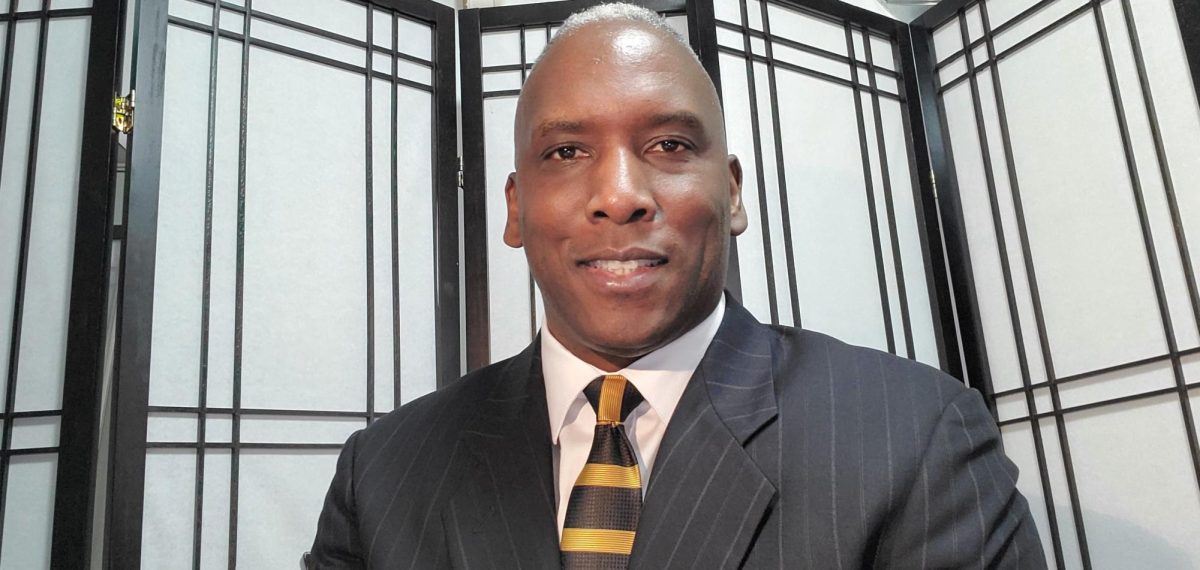

“[Coach Wideman] is one of the reasons why FAAM has survived for [over] 50 years. This is a league where coaches are not paid, yet [they] are committed to give 10-20 hours a week. You can multiply that by the 30 plus years [Coach Wideman has] been involved in FAAM; that’s how many hours of his life he’s donated to [the league],” said Alando “Spud” Massie, a long-time coach and devoted member of FAAM. “He is what FAAM stands for.”

Years prior, in his varsity Kits uniform, Kenneth overcame adversity and helped the team advance to the state competition.

“My junior year of high school, I broke my leg in three different places,” Kenneth said. “When it healed up, I asked my doctor if I could return to basketball and she said ‘Kenneth, I’m not going to say you can play, but it’s your choice.’ So my senior year, in 1964, I helped take the Evanston varsity team downstate. And it was very gratifying.”

A year after graduating from ETHS, Kenneth was drafted into the armed services. Today, you will often find him wearing his Vietnam veteran cap.

“I went to Vietnam and spent 22 months in the military,” he said.

Though a man consumed by wanderlust, Kenneth affirms that he will always be drawn back to Evanston.

“I’m a true Evanstonian. I love what the city has to offer and I love the people,” Kenneth said. “I think Evanston is one of the greatest towns in the United States.”

Kenneth attributes his longevity to his dedication to dance.

“I love to dance to music. I would dance to a whole album—both sides—without stopping. I would dance and dance and dance. Maybe that’s why I’m in the shape that I’m in today. At 78 years old, I think it is because I [have been] dancing my whole life.”

Massie attests to his genuine and altruistic character, describing Kenneth as a pillar of Evanston’s Black community who has touched the lives of many.

“[Coach Wideman] has been a staple—a concrete mentor—in the Black community for many, many years,” Massie said. “He [is] very influential, very respected amongst his peers and a great role model. If he preaches [it], he lives it.”

While Kenneth has yet to spend a cent of the monetary compensation he received, he feels fortunate to have been chosen and is proud of the City of Evanston for taking significant strides towards redress.

“I wouldn’t turn in my life for anything. I don’t have any complaints. It’s a blessing for me to be here today. I didn’t know how long I was going to live, but I’m living a good life,” Kenneth said. “Just keep living and you will see it.”