159 years ago, Gen. William T Sherman proposed the Special Field Order No. 15 that 400,000 acres of abandoned Confederate land be seized and granted to the thousands of newly free Black families. Those families would be granted 40 acres of land, as well as mules no longer of use to the military. But upon President Andrew Johnson coming into power following President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, the order was repealed, and the land was returned to the white Confederates who held initial ownership of the properties. While this motion never came to fruition, it marked the first attempt at creating a reparations plan for Black people to receive after the hundreds of years of slavery they had to endure.

It took until 1989 for a similar clause to be proposed—when Representative John Conyers introduced H.R. 40 to Congress. He created this motion after the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 paid reparations to the Japanese-Americans who were forced into internment camps during World War II. Through H.R. 40, he aimed to bring attention to the study of the impact of slavery in America as well as to begin the installation of reparation programs on a national level.

But on a municipal level in Evanston, reparations were not introduced until 2002, when a resolution was created by former Alderman Lionel Jean-Baptiste. His resolution was primarily focused on reparations at a national level, following the federal act that was H.R. 40.

“I’ve always been part of the movement for equity in society, as someone who grew up in Haiti and understood what it took to bring the end of slavery,” Jean-Baptiste said. “We know that African Americans have waived major struggles, civil rights movements, to be able to vote, be able to participate, be able to get some fairness in society.”

Jean-Baptiste attended a World Conference Against Racism, also known as Durban I, held in South Africa in September 2001. At the conference, he heard from other nations regarding the discussion of slavery and slavery-related issues. What came out of the conference was a resolution that declared slavery, slave trade, colonialism and apartheid to be regarded as crimes against humanity.

Kamm Howards, national and international reparations activist, emphasizes that the conference was a key aspect in beginning the global and national push for reparations.

“The countries that committed those crimes were economically empowered and rich, and the people in [the] countries that were victims of those crimes [were] economically impoverished. You [still] see that today,” he said. “What I’ve tried to do in America, and even in my travels, is to highlight that the foundation in which we all build these modern reparations movements rests in the work that was done in 2001 at the World Conference.”

Jean-Baptiste viewed the conference as a stepping stone for developing movements and programs in response. “Coming out of [Durban I], [the] question was, ‘What else do we do other than [a] declaration?’”

With his initial resolution coinciding with the goals of H.R. 40, he believed Evanston was the right place to begin—especially when it came to better education for the future generations.

“We desegregated schools early [following] Brown versus Board of Education [and] have been progressive not only at the level of the government, [but] between Northwestern and ETHS,” Jean-Baptiste says. “But from a broad kind of standpoint of supporting the federal bill, [we needed] to look locally at the impact of slavery and slave trade, teach it so that the community is not in the dark because we teach the history in our schools.”

He believed that the first step should begin with incorporating it throughout history curriculums—to expose the accurate past of Evanston and reveal to students the local impacts of slavery within the community. As a member of Evanston’s city council, he got in touch with several Northwestern professors who were in support of the initiative to teach and encourage students to achieve equity.

“At [the] time, I don’t think the research was there to expose the local harm of redlining,” Jean-Baptiste said. “What people were learning to say [was] that we are now at the point of understanding: you need to do the research identified. You need to identify a source of revenue to remedy.”

But over the next 17 years, Jean-Baptiste’s push for reparations found no momentum in fueling the movement for cash payments. That was until 2019, when then-Fifth Ward Alderwoman Robin Rue Simmons noticed a pattern of disenfranchisement in the community and sought to rectify it.

“There was a moment that I was sitting in the aldermanic library, looking at our data and feeling away about all of my friends and families and their parents and grandparents that had to leave Evanston because they couldn’t afford it or they didn’t feel like this was a place for them. And in that moment, in February 2019, my 20-plus years of service and business evolved to reparations. And I haven’t looked back; I haven’t backed down from that.”

Rue Simmons drew from Jean-Baptiste’s work, recognizing specifically the City of Evanston’s contribution to the cycle of inequity.

“I was really amazed when Ms. Rue Simmons took the lead and called for reparations that address repairing the inequities in housing and economic disparities,” Jean-Baptiste said.

A year before then, at the beginning of 2018, former Seventh Ward Alderwoman Jane Grover, alongside then-mayor Steve Hagerty, introduced the city’s first Equity and Empowerment Commission, where Evanston residents would make recommendations to address the city’s systemic inequities. Before beginning her pursuit for reparations, Rue Simmons became heavily involved in the commission, looking for ways to best service the community in which she grew up.

“We were looking at all of the past practices and policies, where we had contributed as a city to inequities in this community. We had two aldermen, Alderman Robin Rue Simmons and Alderman Cicely Fleming, who were both active with that equity and empowerment commission and both went to the commission on separate occasions and said, ‘Listen, we need to do more to account for the past harms that we’ve caused black to Black Evanstonians,’ and Cicely Fleming’s request of the committee was that she wanted a resolution to come before the city council that acknowledged what the city had done to contribute to those to those harms,” Haggerty said. “Ultimately, Simmons really pushed in and was like, ‘No, I want more. I want reparations. I want us to be the first city to do that.’”

For Rue Simmons, the Equity and Empowerment commission provided her with an outlet to address harm in the community, which she took one step further in advocating for reparations.

“I knew that committee was tasked with doing racial equity and justice work, so I made the recommendation to that committee, and that’s where it started,” Rue Simmons said. “I had a warm reception from that committee, and we partnered, we locked arms, we engaged with the community, we took feedback and we put together an initial recommendation that went to the city council.”

Simultaneously, in order to demonstrate why there was a need for repair, then-City Clerk Devon Reid was tasked with compiling the initial historical evidence to present to the City Council.

“Very early on in the process [Rue Simmons] came to me as the city clerk and said that she believed in municipal reparations and was looking for research to back up the call for local reparations and had had some difficulty getting traction with other groups, so she said, ‘I should have gone to the clerk as the records keeper in the first place,’” Reid, now the Eighth Ward councilmember and a member of the reparations committee, said.

On April 18, 2019, this research accumulated into a memorandum entitled ‘The Case for Reparations,’ where the City Clerk’s office walked through the ways in which Evanston has perpetuated racial discrimination and created roadblocks for Black Evanstonians to accumulate generational wealth. To Reid, this act of uncovering harm aligned with the values of his office as a conduit of information between the city and people.

“The clerk’s office, to me, is meant to be an office where truth is sought, and I think that reparations, a large part of it is truth telling, so that’s why I thought it aligned with the values of the clerk’s office,” Reid said. “The clerk’s office values are the city’s values, and the city of Evanston believes in justice and equity and fairness. And I think a well designed reparations program hits all of those points.”

Reid then made the recommendation that Rue Simmons continue researching and draft a more specific plan for reparations.

“From the research gathered, we can reasonably surmise that a history of city-mandated discrimination including exclusionary housing policies…federal government redlining… divestment from Black communities…has led to the decline of socioeconomic status and hindered the ability to acquire wealth for Evanston’s Black community,” the memorandum read.

Following the memorandum’s release, in June 2019, the planning process officially began with the City Council’s adoption of resolution 58-R-19, Commitment to End Structural Racism and Achieve Racial Equity. The resolution looked to acknowledge the ways in which Evanston has perpetuated racial disparity and pave the way to dismantle the systemic effects of its racist past.

“The City of Evanston government recognizes that like most, if not all, communities in the United States, the community and the government allowed and perpetuated racial disparity through the use of many regulatory and policy-oriented tools. Some examples would include, but not be limited to the use of zoning laws that supported neighborhood redlining, municipal disinvestment in the Black community; and a history of bias in government services,” the resolution, which passed unanimously, read.

Just one month later, in July 2019, two gatherings were held by the Equity and Empowerment Commission to engage community members and understand what type of repair they were seeking. Shorefront Legacy founder Dino Robinson explains that when Rue Simmons initially began this process, she wasn’t looking specifically at cash reparations as the solution.

“She started doing research on ‘What can I do to improve the community I grew up in?’ And she wasn’t thinking first about reparations, she was thinking about servicing the community,” Robinson said. “But in our research, we saw that this is something more, and then she also partnered with the Equity and Empowerment Commission, and they did a series of two town hall meetings to assess the Black community. “

In these meetings, residents created a laundry list of items in need of repair in their community, identifying five main categories: housing, education, finances, culture and economic development. Life-long Black resident Rose Cannon, now an avid critic of Evanston’s reparations program, was in attendance and noticed the prevalence of housing concerns.

“They did a whiteboard, and they were asking us what we thought reparations were, and so everybody was just tossing out different things,” Cannon said. “But the major thing that stuck out is that nobody could afford any housing here in Evanston, because Evanston is very, very expensive to live in.”

Robinson would go on to write the report that served as the basis for Evanston’s final program, but before that process began, the Equity and Empowerment Commission brought in an exhibit on redlining in the United States that he was asked to add on to with an Evanston specific exhibit.

Redlining Evanston was the result, which included redlining maps, blown up to the size of a door, and a timeline depicting housing issues from 1860 to 2000. From August 26, 2020 until October 20, 2020, Evanstonians could visit the exhibit, serving as insight into the city’s history with housing discrimination.

“You could go there and literally see past ordinances, you could find past mortgages, and you could see exactly the type of discrimination that we had legalized through the policies and practices of the city,” Haggerty said. “It was very moving. Thousands of people in Evanston saw that, and so when Robin Rue Simmons says, ‘Hey, I think we should have reparations, and we should be the first city to do it,’ it really [went] through pretty uncontested. There wasn’t much division here in Evanston.”

While the exhibit was still attracting visitors daily, on Sept. 9, 2019, the City Council accepted the recommendations of the Equity and Empowerment commission, forming a new reparations subcommittee headed by Rue Simmons and then-Eighth Ward alderwoman Ann Rainey. Over the next two months, the subcommittee worked alongside city staff and outside organizations to develop the preliminary plan for reparations.

At the Nov. 14, 2019 City Council meeting, Rue Simmons, Rainey and then-Second Ward Alderman Peter Brathewite put resolution 126-R-19 up for a vote, which would first create a new reparations committee; second, define areas of repair; and third, establish a reparations fund through the Adult Use Cannabis Tax: a three-percent tax on all cannabis sales, until the fund reaches $10 million.

“Resolution 126 R-19 really launched this work,” Rue Simmons said. “It established our reparations committee, it established our reparations fund, it prioritized our areas of repair, which is housing, but it also includes economic development and educational initiatives, and lastly, it seeded our work with the first $10 million of our recreational cannabis sales tax.”

At the time, Sixth Ward Councilmember Thomas Sufferdin was the only council member to vote against the resolution, arguing that it was irresponsible to dedicate the funding without yet knowing its intended purpose.

“In a town full of financial needs and obligations, I believe it is bad policy to dedicate tax revenue from a particular source, in unknown annual amounts, to a purpose that has yet to be determined,” Sufferdin wrote in a newsletter to his constituents following the vote. “Individuals and institutions who wish to make contributions to the City of Evanston Reparations Fund may do so. I voted no to funding reparations with recreational cannabis revenue not because I don’t support the City taking responsibility for the role it played in disadvantaging our African American residents, but because it is bad policy.”

But Haggarty argues that by having a funding source established before the program was up and running, they could focus more on its substance without worrying about securing the money.

“You can look at the U.S. Congress. They have been for decades talking about reparations and part of it is like, ‘Well, what would it do? How would we define it and who would qualify for it?’ They haven’t even gotten to the money piece,” Haggerty said. “We flipped it; we figured out the money piece first.”

Another important aspect of the funding is in its symbolic nature. According to a Nov. 20, 2019 memorandum, in Evanston, Black individuals made up 71 percent of arrests for cannabis possession in the preceding three years, despite only 16 percent of Evanston being Black. Thus, Reid explains that by directing the funding from cannabis, an extra level of repair is made.

“We understand that the war on drugs and particularly cannabis has not been successful and has led to disproportionate harm on communities of color and communities that experience poverty,” Reid said. “So, by having that recognition that the war on drugs and cannabis specifically has had that history, using the revenue from the cannabis sales tax seems like a really good idea. That continued our push toward equity and fairness. Really having the funding in place, or a promise of the funding in place early on, made everything else easier.”

However, when explaining to the community from where the funding for the program would come, current reparations committee member and lifelong Evanston resident Carlis Sutton, who is eligible for reparations himself, found that many were concerned with its source.

“The funding was a little concerning again to many of the people who are part of the church and elderly,” Sutton said. “You’re using marijuana money, so we came across questions like, ‘What, are you running a drug addict program? Are you drug dealers?’”

In order to relieve these concerns and shape the program to fit the needs of the Black community, residents were able to give feedback and hold conversations with stakeholders.

“Community input played a huge role in that every step of the way, the community was kept in communication,” Reid said. “What was really in some ways leading the charge for the various programs, and really helping to build the cases for reparations, was the folks who shared their personal stories, and family stories that had been passed down. This is really a community driven process.”

Following the establishment of the Reparations Committee, which would comprise initially of Rue Simmons, Rainey and then-Second Ward alderman Peter Braithwaite, a series of town halls—totaling 15 before the program was passed—were held. It was through these meetings that the committee identified housing as the first sector of repair.

“Overall, the goal is just to help repair and restore our Black communities. In the early stages of coming up with repair, there were a lot of community-focused meetings where we were listening to the concerns of our black residents,” Braithwaite said. “The issue of housing, housing discrimination and lack of affordable housing were just a short list of many concerns that were raised by our residents. Because housing discrimination was such a big concern and the fact that we were able to prove it, it made sense to the committee that that would be the first step of repairing and restoring our Black community.”

Initially, the city planned to hire a consultant to conduct the bulk of the program’s research, but Robinson, who had, at that point, been conducting said research for the past 20 years, went to the committee and offered his expertise.

“A few weeks later, city staff contacted me, and we got on a group call with various other entities in Evanston, and I became the project lead in creating a 20-page report called Evanston’s policies and practices directly affecting them from reaching the community in 10 days,” Robinson said.

From the report, entitled ‘Evanston Policies and Practices Directly Affecting the African American Community, 1900 – 1960 (and Present),’ which was co-authored by Evanston History Center’s Direct of Education Dr. Jenny Thompson, the committee was able to back up the testimonies of Black Evanstonians with historical evidence.

“The 20-page report grew to an 80-page report that not only talks about trying to find any legal arm in that we did find a ordinance that the city runs and that dealt with housing restrictions. But then we also dealt with the culture of discrimination and Jim Crow that the City of Evanston participated in, including housing and education, location, education, health—all these things that are played into it. And, so, with that, they’re really utilize that report to designate a time period of harm to a certain point, so from 1919 to 1969. We’re working to improve on our report to extend it beyond 1969.”

Fifth Ward councilmember and current reparations committee member Bobby Burns believes that by going so in-depth on the roadblocks the city created for Evanston’s Black community, they affirmed the need for reparations from a legal standpoint.

“Reparations is not a social equity program, per se. I compare it more to a settlement agreement that will come out of a court proceeding, where someone has wronged and been wronged, and in the courts, you use the system to settle the disputes by identifying who’s at fault, and then there’s an agreement to try to make that person whole, as best as you can,” Burns said. “And that’s how I see reparations; there was a wrong that was done to people that live in a certain area, and we now have a redlined area, specifically in the Fifth Ward. And then they have a claim of being disenfranchised, discriminated against in ways that affected their health, but also impacted their ability to build wealth and develop financial security for their families.”

From there on out, city staff, residents and outside consultants worked together to mold a reparations program that would address the grievances found in Robinson’s report. Throughout this process, the program went through different changes with regards to who would receive the money and how they would be able to spend it.

“One of the thought processes early on was that maybe the funding should be restricted to use only in the Fifth Ward,” Reid said. “And very early on, I raised concerns with that, because it seemed as though that, although well intentioned, we would be continuing the pattern of redlining, which is to say that African Americans could only live in the Fifth Ward. It would be essentially trying to solve the ills of redlining with the ills of redlining.”

Again, community input played a role in shaping the program’s guidelines.

“The program had years of community conversations leading up to the first funds being disbursed,” Reid said. “There were town halls held, there were just numerous meetings held with stakeholder groups to craft this, and then the reparations committee every quarter continues to hold town hall style discussions, where we have the community come in, and we answer any questions that folks have, we hear testimony from folks, and we continue to do that.”

In these conversations, community members voiced their opinions, both in support of the program and to raise concerns over its direction. On Feb. 25, 2021, the Reparations Committee announced their preliminary plan for payment, which would provide $25,000 housing grants to those harmed by housing discrimination as well as their direct descendants. Despite her initial involvement with the Equity and Empowerment Commission, Fleming soon split from Rue Simmons, noticing that the concerns of her constituents weren’t being addressed.

“There were some people who were really against it, and there were some people who thought it was great. There were a lot of public comments, and people felt like, if you were against it, you didn’t get that much time, but if you were for it, you got a lot more time to talk,” Fleming said. “I think the way in which it was celebrated, given there were a lot of people who had concerns about it, it felt like we don’t care about your concerns, and that Evanston only wants to do things to be the first and historic. To say that we did something, this is our first iteration of it, and we realize it’s not perfect, but we want to get something started is very different from celebrating like that.”

One of Fleming’s main issues with the program was that it wouldn’t put cash in the pockets of recipients. Rather, an outside organization, Community Partners for Affordable Housing, would manage the funds and disperse it to contractors or financial institutions chosen by each recipient.

“It was going to be another kind of program in which, if you qualify, the city would help you do these other things, where as to be reparations, it’s about giving people financial compensation for harm that was caused,” Fleming said. “It should not be tied to anything or limited based on what they want to use the money for.”

This clause in the program—being regulated in how the money could be spent—prompted Evanston residents Sebastian Nalls, Kevin Brown and Cannon to form Evanston Rejects Racist Reparations. On March 6, 2021, in preparation for the council’s vote on the proposed program, the organization staged a protest in front of the Med/Men cannabis dispensary.

“If we only settle for housing … or say, ‘We don’t have a plan right now, but months, years down the line, we’ll do something else,’ we’re leaving the door open to a lot of interpretation on what reparations actually means, and that’s unacceptable,” Nalls said the day of the protest, speaking to a crowd of 50.

That same day, Nalls held a Zoom forum, inviting Rue Simmons and Robinson to address the community’s concerns.

“There are no restrictions on how the funding is used, as long as it’s used to build wealth in your home. …We have more work to do. …This is only one initiative out of many to come. There will continue to be a public process, just like there was in 2019 for us to get to this point…We’ll come up with a more efficient community process so that we can hear from the residents,” Rue Simmons said in response to the critics on the program.

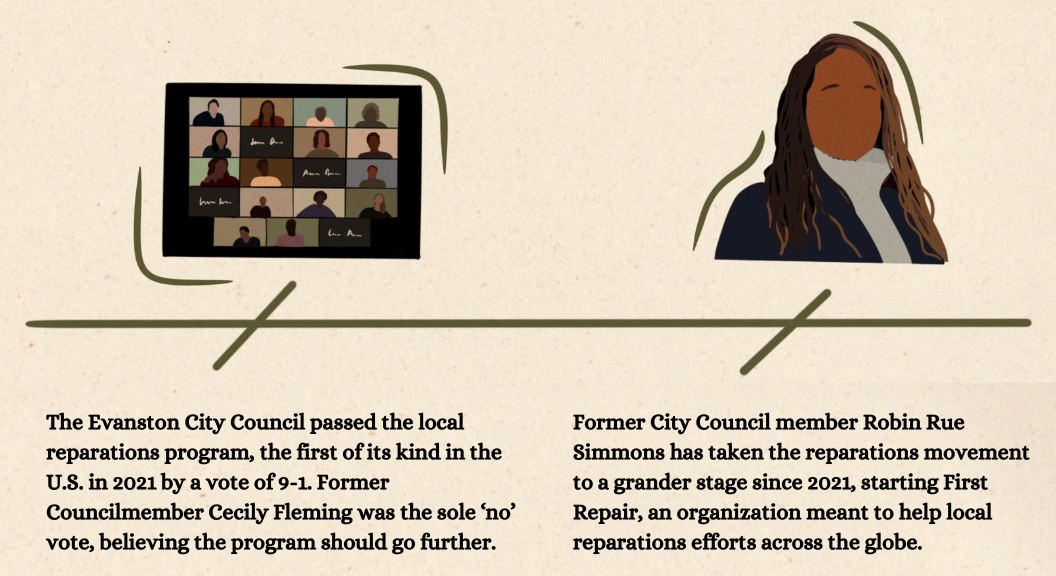

Despite the momentum that Evanston Rejects Reparations was building, on March 22, 2021, the Reparations committee put the final program to vote, passing resolution 37-R-21 8-1. Named the Restorative Housing Program, its goal is to revitalize Black-owned homes in Evanston, increase Black homeownership, build intergenerational equity among Black residents and improve the retention rate of Black homeowners in Evanston through a $25,000 stipend that can be put toward housing payments, home improvements or mortgage assistance.

To qualify for the funding, Black Evanstonians must either have lived in the city between 1919 and 1969, referred to as ancestors; be the direct descendant of a Black resident between 1919 and 1969; or submit evidence that they suffered housing discrimination due to the city’s policies after 1969. The initial resolution put aside $400,000 of the Adult Use Cannabis Tax for 16 ancestor grants.

“Ancestors are the individuals who were most directly affected by the harm the city caused, and so, each applicant in that situation is in the queue to receive reparations,” Biss said. “The next tranche are what we call descendants, which is to say, African-American Evanstonians who had parents or grandparents or potentially great grandparents who were in that previous situation. So, these are individuals whose family wealth would have been directly affected by the harvest at cost.”

While he wishes more thought was put into the amount of money each grant was worth, Reid explains that they landed on $25,000 from past examples of reparations.

“I will say that I wish that the city took more time to really come up with solid math as to how we got to $25,000. It’s primarily based on looking at some other really prominent examples of reparations, both in America and elsewhere,” Reid said. “If you look at the Japanese internment camp reparations bill that passed, $25,000 was the number that those folks received, and well, $25,000 from the 1980s to now is worth a very different amount.”

Fleming, the only council member to vote against the resolution, felt that without cash payments—no matter the amount—the program wouldn’t fit a true definition of reparations.

“I did not like that it was tied to our house, and I felt that it was not really about giving them repair for the harm that was caused, it was about trying to keep African-American people in Evanston, keeping our diversity numbers high,” Fleming said. “Not that people don’t need money to repair their house, but I heard from a lot of people who were like, ‘I just want money to do other things.’ People talk about wanting to have money to help their kids pay for college and things that were of value to them that weren’t about their house, and we have a lot of people who don’t own homes.”

Because of the nature of the restrictions, the funding couldn’t be used for either rent payments or property taxes.

“I had a lot of residents in my ward who talked about property taxes, and they were losing their houses because of property taxes, and this program didn’t even allow you to use property taxes,” Fleming said, “Also, just fundamentally to give the money to banks that had been historically harming Black people and then the bank is going to manage your dollars for you also just felt very offensive to me. I felt like it was not about true freedom for African Americans. It was about managing them in another way.”

While Burns had been in support of cash payments from the beginning, he explains that, at the time, the committee held concerns over legal challenges to the program.

“In the exploration of it, there were some concerns on whether or not it would be considered personal income and therefore be taxed. There were also concerns about if the program would be more vulnerable to court challenges, if we provided direct cash benefits, as opposed to, funding for housing related services or improvements, and I think that’s the only reason why there was hesitation initially to allow direct cash benefits,” Reid said.

Following the vote, Fleming noticed a divide between the Black community in Evanston—those in support of the program and those that felt it didn’t go far.

“It divided the Black community, and it continues to divide the Black community. It made a lot of people feel like this is just another way of slapping some kind of racial equity term on stuff that we’re doing only for political gain,” Fleming said. “There were a lot of people who were with it, celebrating it, and then when they found out what it really was, were very disappointed.”

On May 21, 2021, the current reparations committee expanded to include resident participation. Rue Simmons, having decided to not to run for reelection, took one of these spots alongside Bonnie Lockhart, Claire McFarland Barber and Sutton.

When choosing who would sit on the committee, stakeholders looked to the different organizations that service the Black community. Through her involvement with Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Incorporated, lifelong Evanston resident and estate planning attorney McFarland became aware of the open positions and after being selected through an application process, has sat on the committee ever since.

“We received outreach asking if we could help disseminate information about this reparations program and have some of our members join the efforts,” McFarland said. “That’s how I first learned about it, and there was a meeting to which I was invited, and that was not just the Black fraternities and sororities graduate chapters. It was also the NAACP, some of the faith groups, Interfaith Action Group, and just various groups.”

With Second Ward Council Member Krissie Harris, Burns and Reid working alongside the selected residents, the committee was tasked with overseeing the disbursement of funds and advising the next phase of the program.

Beginning on Sept. 21 and until December 15, 2021, Black residents could submit an application for funding to the committee, providing documentation that establishes proof of residency in Evanston between 1919 and 1969 for either themselves or direct ancestors. In preparation, drop-in hours at the Fleetwood Jourdain center were made available to assist residents in obtaining and submitting documentation, while individual wards held meetings to educate their constituents.

“After the program was approved, I did have Robin Rue Simmons come to a Zoom to talk about the history, rather than talk about the reparations program to my residents, but I’ve had tremendous positive views,” Seventh Ward Council Member Eleanor Revelle said. “I have a couple of residents with questions, who aren’t clear about the program, and they think that we’re trying to repair slavery, but that’s not what we’re doing.”

And on Jan. 22, 2022, the first 16 ancestor recipients were chosen, dispersing a total of $400,000 in grants. In a gathering at the Fleetwood Jourdain center, Rue Simmons selected the first recipient—Ramona Burton—from a drawing of 140 white bingo balls to represent the 140 eligible ancestors, marking the moment when the first Black person in America received municipal reparations.

However, after distributing the funding to the first 16 ancestors, the committee hit a roadblock in getting grants to the remaining ancestors. Despite having set aside the revenue from the Adult Cannabis Use tax, the city didn’t hit its projected cannabis sales, resulting in a deficit in funding for the program.

“Evanston didn’t really get to see the cannabis sales as we thought they would because COVID hit, and that changed people being out and purchasing and all of those things,” Harris said. “So, the numbers that we thought we would articulate didn’t quite come to fruition right away.”

This meant that after a year of accumulating the tax, only the initial 16 ancestors were able to receive their grants.

“We only have one cannabis dispensary in the City of Evanston, and the revenue from that dispensary was coming in slowly. There are two groups of reparations recipients: ancestor recipients and direct descendant recipients,” Assistant to the City Manager Tasheik Kerr said. “So, after the first year, we could only do 16 ancestor recipients based on the revenue that was coming in from the cannabis dispensary.”

To bring in more funding, the committee looked to the city’s ARPA funds, which would have set aside its remaining $5 million to the reparations program. In a memo to City Council, Kerr wrote, “At the time of the passing of the resolution, it was anticipated that the City would have three cannabis dispensaries operating in the City; however, the State of Illinois delayed the distribution of the Conditional Adult Use Dispensing licenses. It was not until July 2022 that the Illinois Department of Revenue released a list of recipients. To date, staff has fielded one phone call from a prospect who intends to conduct additional research on the Evanston market. Since various market and local conditions influence a potential dispensary operator to locate in a city, uncertainty remains on whether the City would have another cannabis dispensary.”

Instead, the committee secured funding through the transfer tax of real estate valued over $1.5 million, bringing in $10 million over 10 years and doubling the total funding for Evanston reparations.

“After we got that process going, the distribution was easy. We could just get it out the door,” Kerr said.

More than a year after they first received their grants, siblings Kenneth and Sheila Wideman hadn’t spent a cent of their funding—a direct result of them being renters, with no property to invest in. On March 2, 2023, the committee voted to allow the siblings to receive their funding in cash, with only Reid voting against the motion in hopes of completely amending the program to allow for all recipients to receive cash payments.

“There was a lot of convincing that had to be done because folks were concerned that direct cash payments would embolden or enrage the anti-reparations groups and encourage them to file a lawsuit against the city of Evanston,” Reid said. “The hard part was convincing folks that Evanston needs to continue to be bold, to be brave and to push forward with this effort, understanding that our program is grounded in solid evidence and reasoning.”

However, in a 5-0 vote on March 16, 2023, the committee did vote to expand the funding to cash payments, allowing recipients to spend or save the money in whichever way they chose—whether housing related or not.

“We learned that it’s difficult for the city to truly address the various complexities of the impact of our discriminatory housing policies if we restrict these funds, and we don’t allow folks direct cash payments,” Reid said. “We discovered that, with direct cash payments, it gives folks the dignity of making decisions for themselves, and it gives the city the efficiency of getting the money out of the door faster.”

And by getting rid of the restrictions on the grants, more residents could get behind the program as a true interpretation of reparations.

“Reparations are really in the eye of the beholder; it is the person who is being repaired, and in that sense, if the folks who looked at the reparations program as it was initially designed and said, ‘Yes, to me, that counts as reparations; that is something that would begin to address the harm that my family has faced as a result of the city’s policies,’ it was reparations for those folks,” Reid said. “But, I do think that it was important to make sure that the program could be seen as reparations by the broadest possible audience, and that’s what direct cash payments allowed us to do.”

Burns feels similarly.

“In order for something to be considered a reparations program, the current community has to decide what reparations looks like, and you can view that at the collective level or at the individual level,” Burns said. “I think, in its purest form, you want to do that at the individual level, because every household may need different things to advance themselves, and so cash payments allow the flexibility that the restrictions that we initially adopted did not allow for.”

As of Jan. 8, 2023, 117 of the 140 verified ancestors had received their funding, with 454 direct descendants in line to be selected.

“Not long ago, the reparations were just a minor radical thing that was viewed as just a pipe dream, and now it’s a reality. And what that means is that we’re close to normalizing it as a responsibility, but once we normalize the idea that if you’ve done as an institution this kind of harm to you, you don’t need to close up shop, you don’t need to cease to exist—you just need to come to grips with the harm you’ve done and then take meaningful real steps to repair it,” Burns said. “Then, once we establish that as an expectation, the country can move past this question of ‘Is reparations too radical?’ and replace that with the conversation of ‘What’s the correct way to fulfill this moral responsibility?’”