Each year, students across Evanston’s public school system learn about the destructive, racist system found throughout our country when Jim Crow laws started in the 19th century. Although these laws were primarily being enacted in the southern half of the United States, the lingering effects of these laws in the north, including the Chicagoland area, still persist.

Illinois has one of the longest legacies of pre-Jim Crow segregation in the country. “Black Codes” were state-level laws restricting the rights and movements of African Americans, and although they were most famously implemented in southern states after Reconstruction, antebellum Black Codes were primarily in the North, since that’s where freedmen primarily lived. Illinois passed laws restricting basic rights to African Americans as early as 1819. The Illinois Black Law of 1853 went further by prohibiting all visiting Black people from staying in the state for more than 10 days and forbidding them from seeking residency there. In Evanston, the redlining and segregation that started from these policies decades ago still exists.

“We typically think of Jim Crow as a kind of arrangement that was manifest in the American South, up until around the 1960s, with the passage of the 1964 Act,” Brett Gadsden, Northwestern Professor of 20th-century African American History, explains. “But I think we can talk about Jim Crow more nationally, as a system in which African Americans were systematically segregated and subordinated not just in the South, but also in the North, and in the West and the Midwest.”

In 1919, the City of Evanston hired urban planning firm Harland Bartholemew and Associates to start zoning the city’s neighborhoods; the company drew up the ordinance that codified segregation in Evanston. The city council approved the plan in 1921, and until the passage of the city’s Fair Housing Ordinance in 1968, all Black residents were barred from living outside of Evanston’s west side. To this day, Fifth Ward residents don’t have access to a public school in their ward, having to transit to neighboring wards for elementary and middle school.

Looking back in the 30s, we continue to see further racism federally. The Federal Housing Administration advocated for use of racially restrictive covenants that forbid “the occupancy of properties except by the race for which they are intended” (FHA Manual, 1936), a policy that made certain properties and neighborhoods impossible for Black residents to move into.

Another of the FHA’s harmful practices was the perspective that Black people lowered property values of a neighborhood. In Evanston, keeping Black residents from lakefront and northwest regions was a practice that, for white Evanstonians, was intended to “protect” the values of their homes.

Because of Evanston’s location on the North Shore, holding a prestigious university as well as the lakefront, it is easy to make assumptions about the residents living in the town. Evanston husband and wife Ron and Cheryl Butler, who are recipients of the first trials of reparations in Evanston, state how they hear “especially in the Black community, in Chicago they think if you’re Black and live in Evanston, you have money and you’re wealthy. Every day, we tell people [we are] just like everybody else.”

The lasting impact of these and other discriminatory policies becomes apparent when looking at some basic statistics for Evanston’s segregated wards. In 2019, only 36 percent of Black students in District 65 were proficiently literate, compared to 84 percent of white students. This isn’t the only disparity between wards, as life expectancies vary wildly from district to district, and areas dominated by Black residents have a disproportionately low life expectancy.

According to a map from the City of Evanston, neighborhoods with a higher Black population tend to have an overall lower income in comparison to those that are majority white. As of 2019, median household income in the Fifth Ward was $44,458, whereas in sections of the Sixth and Seventh Wards—areas with an overwhelmingly white population—median incomes were $149,583 and $144,853.

A July 2021 Evanston Impact Study by Northwestern University shows the gap both nationally and locally between average household income for white and Black households. Nationally, there is approximately a $20,000 difference between white and Black households, while in Evanston there is a gap of more than double this—around $41,000.

Housing is one of the most major economic factors when it comes to financial success. Since African Americans have faced all kinds of challenges with housing throughout the past centuries, it has caused major complications for the community.

“It is to the extent that Americans find their source of wealth in their housing that they own, and African Americans have been denied the kinds of opportunities to buy houses in predominantly white sections and enjoy the benefits of the increased valuations of those properties over generations,” Gadsden explains. “That, in large part, explains the wealth gap between Blacks and whites.”

Many assume that Evanston is different compared with the wealth gap issues in other areas of the United States, but Evanston’s residence data proves that this is not the case. For Gadsden, Evanston is seen as a progressive city that is at the forefront of reparations in the United States but is stuck in the long-lasting systemic racism from the early centuries of our country.

“I don’t know what makes [Evanston] unique,” Gadsden said. “What’s striking to me is the ways in which housing segregation operates here in Evanston—a city that prides itself on its liberal and progressive politics—actually mirrors racial segregation of far more conservative cities, like Montgomery, Alabama, or Jackson, Mississippi. The Black community here has been redlined, which very much looks like other cities. African Americans had difficulty buying in predominantly white neighborhoods up and down the North Shore until relatively recently in terms of generations.”

As a conveniently located, developed city on the North Shore, Evanston has drawn wealthier residents over time. But, with this wealth increase, property value rose, making the entire city a more expensive place to reside.

Lifelong Evanston resident, Beverley Mason, has noticed the increase in living costs. “By the 70s, Evanston became a different place. Things were changing, and the properties that parents had owned, the next generations were not able to allot. The neighborhoods began to change,” Mason explained. “We had people moving into our neighborhoods, more Hispanics and Caucasians coming back to the West Side. Because of the market changing, now our houses were affordable to them.”

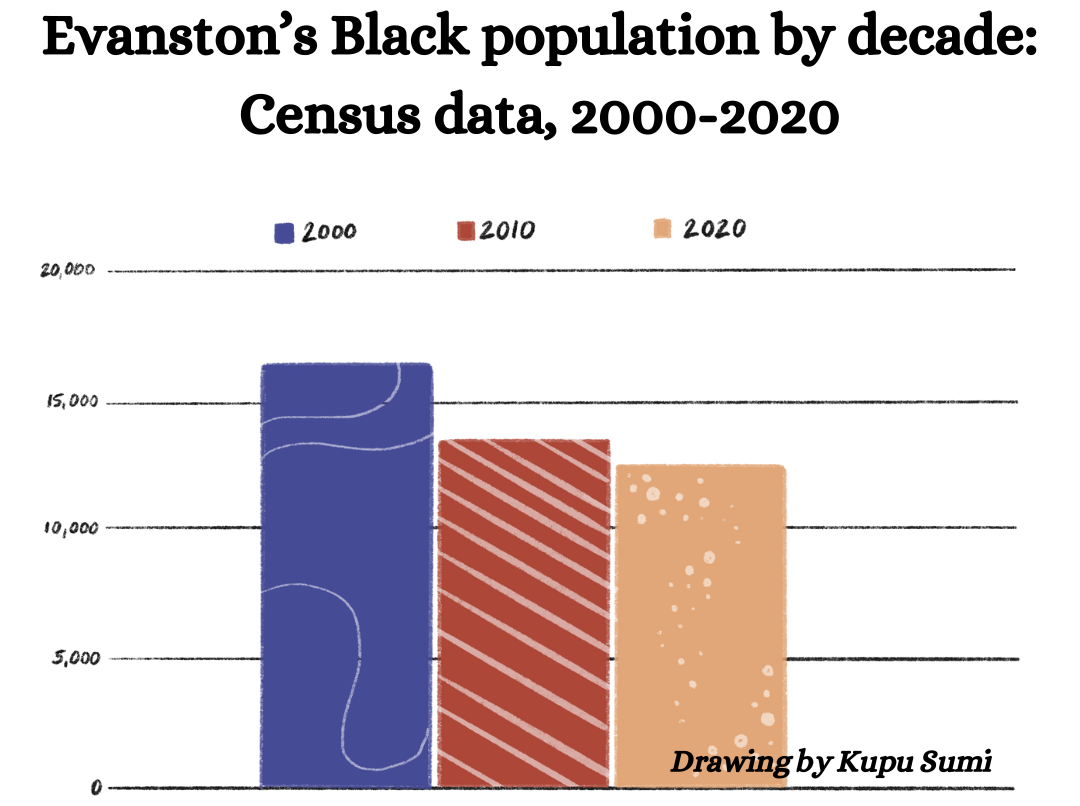

This shift has led to Black residents being pushed out of Evanston. According to the United States census statistics, in 2000, there were 16,449 Black residents in Evanston and 46,444 white residents. A decade later, there was a drop in the Black demographic in Evanston to 13,474 Black residents and a rise in white residents to 48,872.

This divide in Evanston has had an impactful toll on Black people. Looking back to the 1920s, there was an influx of Black homes being relocated to different parts of Evanston because of racist policies, including physically being uprooted from other parts of Evanston into the Fifth Ward.

Setbacks of this nature, not only in Evanston but across the United States, continued the gap between white and Black residents which we have seen grow throughout the years. Gadsden explains that “Blacks who are concentrated in these neighborhoods have, over generations, essentially been deprived of the entitlement that white homeowners have come to expect, which is the accumulation of wealth through ownership of property and the ability to pass down that wealth from generation to generation. I think that’s the biggest tragedy about housing in America.”

When there have been efforts to improve neighborhood concerns, African Americans are faced with a battle stemming from segregation policies from the past.

“In the history of housing in America,” Gadsden said, “wherever African Americans exercised some ambition to improve their housing situation they more often not were met by a variety of institutions—both public and private—that were bent on excluding them from communities like Evanston.”

Evanston’s civic leaders do recognize this disparity with Black residents which has prompted the continued work with reparations, and trying to figure out ways to best serve those specific communities. Black Evanstonians continue to combat these prejudices within our community.

“African Americans have always been resilient people. No matter the amount of discrimination, segregation and violence to which they’ve been subjected. I think that they’ve always taken great pride in their communities, and they’ve done their best to create households and communities that were supportive and safe and nurturing, for the generations of people who’ve lived in those places. They’ve done that, despite histories of redlining and violence and over-policing. [Resilience] ought not to strike us as surprising.”