“I want solutions-based ideas only,” reparations leader Robin Rue Simmons told the crowd. As Evanston residents gathered to express their opinions on the city’s reparations program, the serious, goal-oriented atmosphere was clear.

Rue Simmons didn’t take action to initiate reparations until 2019. Now, in 2024, she is spearheading a push for government action that has expanded much further than Evanston, much further than the United States, even. But Rue Simmons is no newcomer to activism, having started her community centered efforts as a student in Evanston’s public school system. Her experience growing up in the city incited a persisting desire to give back to her community, and spurred her on through the successes—and difficulties—of a lifetime of activism.

Rue Simmons grew up in the Fifth Ward, a predominantly Black neighborhood of Evanston. When talking about the neighborhood today, many residents highlight the racial inequities, such as Evanston’s long history with redlining, that led to the city’s extremely segregated neighborhoods. While Rue Simmons’ later work would go on to address many of these issues, her childhood experience in the Fifth Ward was one of being surrounded by a loving community.

“In the interviews I’ve done, it seems to be edited out just how much joy and love I experienced being a Fifth Ward Evanstonian,” said Rue Simmons. “It’s important to note that in [the Fifth Ward], although we were segregated [from the rest of Evanston], it provided a very nurturing community, one that allowed me to feel safe and valued and confident to be all that I could imagine.”

However, Rue Simmons’ childhood bubble was shattered when she arrived at King Lab, one of Evanston’s many reputed public schools.

“I saw a very different version of Evanston, one that was segregated and one that made it very clear that the village that I came from wasn’t included in the highest and best of Evanston,” said Rue Simmons.

As a direct result, she jumped at her first leadership opportunities, seeing them as chances to elevate the community that had elevated her as a child. She served on student government in middle and high school and was Evanston Township High School’s freshman class president, later being the school president during her sophomore and junior years. During her tenure in student government at the high school, Rue Simmons and her close friend Andrea Swift led student walkouts and worked with other student council members to push for policy change.

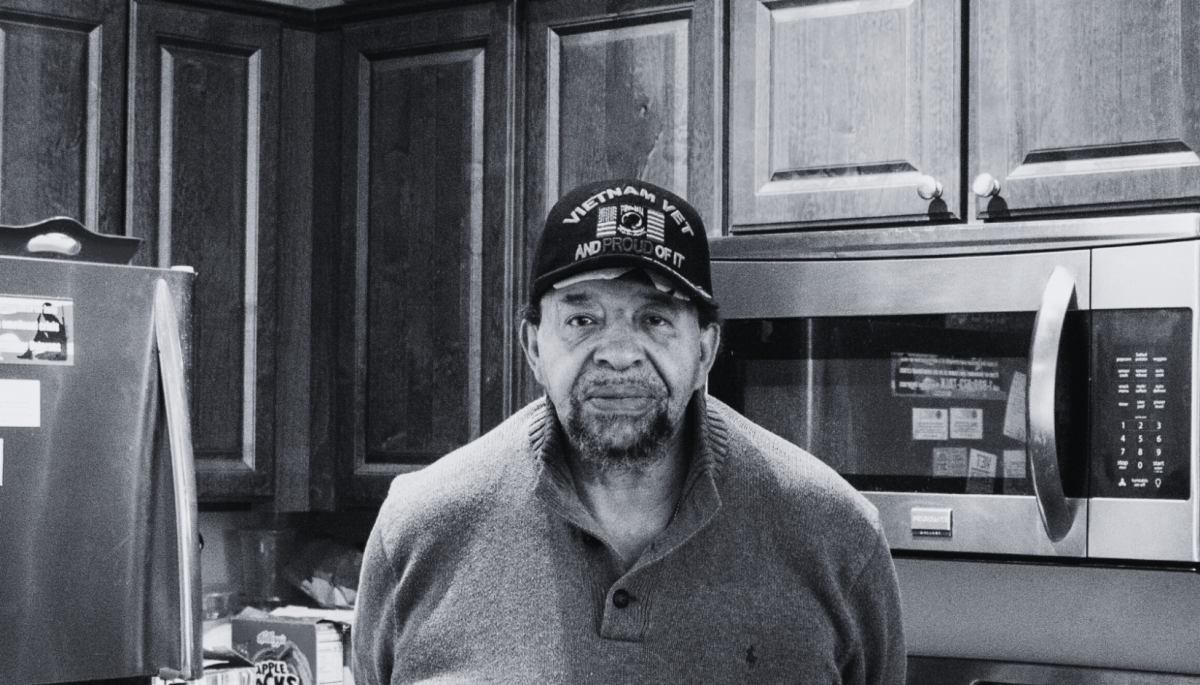

Rue Simmons attributes much of her early community work to older public servants in Evanston that she had as role models, notably Delores Holmes, the director of Family Focus and later Fifth Ward councilmember, and Crawford Richmond, a family member who was very involved in her community.

“I’m very fortunate that we have so many examples of public servants and activists in Evanston,” said Rue Simmons.

After graduating a year early from high school, Rue Simmons went on to college at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Her early graduation and subsequent university choice was not the desired situation for Rue Simmons, but was a necessity for her family at the time. The college experience didn’t provide as many activism outlets as she’d hoped, and she credits those years with being the most disconnected she’s ever been from her community. However, at 19 years old, Rue Simmons became a mother, and that strengthened her resolve to fight for the Black community.

“Motherhood inspired me to take responsibility to change and improve the life circumstances of Black children, being the mother of a Black son,” said Rue Simmons.

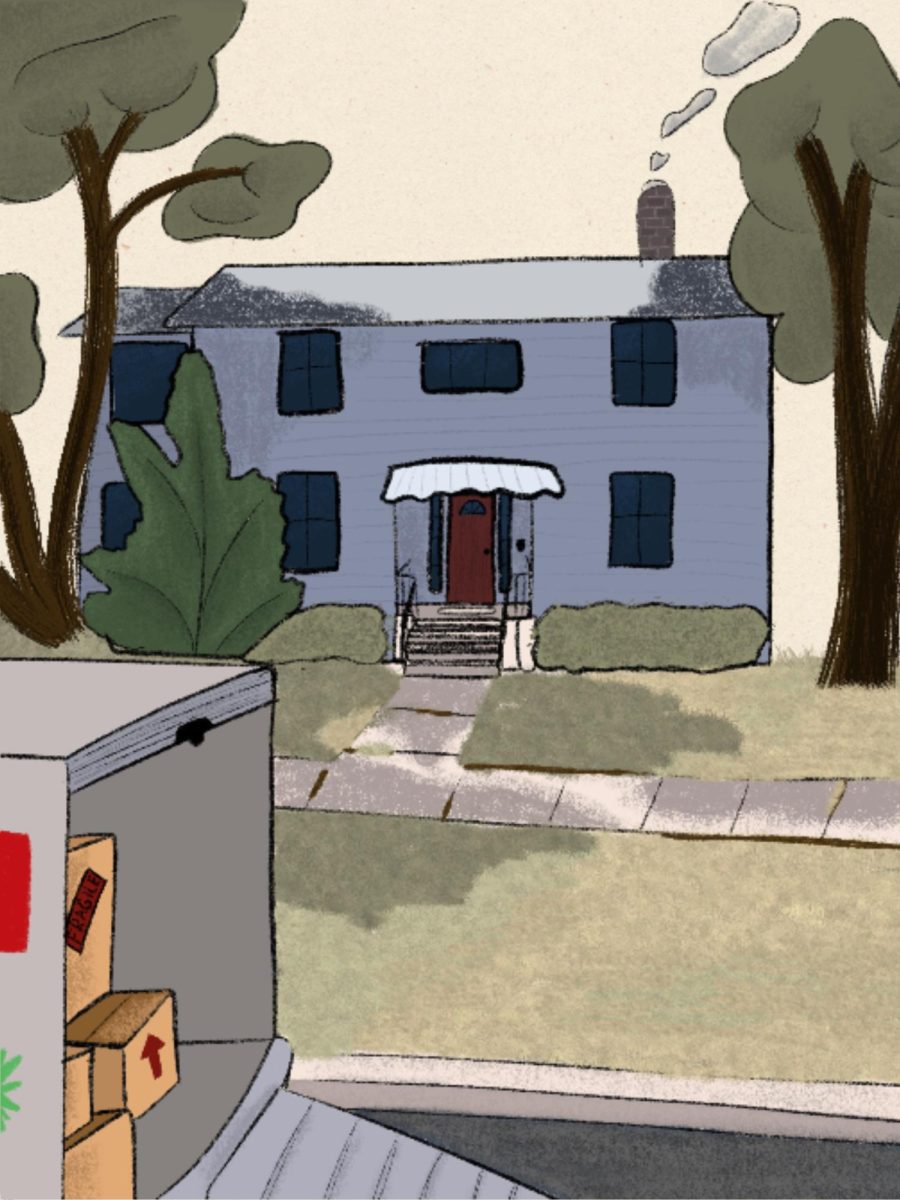

Once her first child was born, Rue Simmons’ priorities shifted, and motherhood opened the door for entrepreneurship, a passion that would continue throughout her life. After attending college, she and her then-husband moved to Michigan, residing near Detroit. Immediately after arriving, Rue Simmons went to school to get her real estate license. Besides the entrepreneurial aspect of retail estate brokerage, Rue Simmons wanted to satisfy a goal of home ownership, and to share that potentiality with her friends.

“I knew [home ownership] was a part of building wealth, I knew it was also a path to supporting healthy families and strengthening neighborhoods from my own experience in Evanston,” said Rue Simmons.

Her first client was a friend from college, and Rue Simmons was able to sell him a home that he had previously rented his entire life. To see him graduate college and buy his first home was a major accomplishment for her, and served as the cornerstone of her friend building his family’s wealth. For a few years, Rue Simmons continued to work in the Detroit area, primarily the Black community on the west side, where her family is from.

Eventually, she decided to move back to Evanston, with the goal of continuing her real estate career in her hometown. However, the prospects of continuing that career path proved low.

“I thought naturally, I’ll be a realtor here in Evanston as well,” said Rue Simmons. “And I got here and signed up for school and studied the market and saw pretty quickly that the market here in Evanston wouldn’t allow me the immediate opportunities that I needed returning home as a single mother of two at that time.”

As a result, Rue Simmons became an affordable housing advocate, and eventually a general contractor focused on developing affordable housing. While not in the business she originally set out for, the opportunities to serve the community as a general contractor satisfied Rue Simmons, and she still owns and manages a few properties in town.

While working as a contractor in Evanston, the discrimination at every level of the homeownership process became even more apparent for Rue Simmons.

“[I saw] those gaps, not just in the acquisition of a home but also the discrimination in lending with predatory lending, the unfair appraisal outcomes for Black families, the challenges for Black contractors to engage in a competitive procurement process and not having the resources to get proper licensing, insurance and bonding,” said Rue Simmons.

Her experiences with discrimination at every level in the Evanston community, coupled with her desire to serve the Fifth Ward, led to a successful bid for candidacy as Fifth Ward Councilwoman. Upon taking office in 2017, reparations weren’t on her agenda, instead, she focused on increasing economic opportunities, specifically home ownership, in her community. At the time, in Congress, politicians like Texas Representative Sheila Jackson Lee were pushing to pass bill HR-40, which would establish a commission to study slavery and its legacies and develop subsequent reparations proposals. Rue Simmons was familiar with and supported the work of Lee, but didn’t focus on it in the first two years of her term. However, that all changed in 2019.

“After two years of service, there was a moment that I was sitting in the aldermanic library, looking at our data, and feeling a way about all of my friends and families and their parents and grandparents that had to leave Evanston because they couldn’t afford it or they didn’t feel like it was a place for them,” said Rue Simmons. “And in that moment, in February of 2019, my 20-plus years of service and business evolved to reparations. Since then, I haven’t looked back and I haven’t backed down from that.”

As with any large undertaking, Rue Simmons identified the need for community support. Luckily for her, support from Evanston residents came in abundance.

“Fortunately, we live in a community that has joined that fight—we jumped in, not knowing how to do it, not knowing how we would fund it, not knowing what type of legal frameworks would be successful,” said Rue Simmons.

The first place she turned to execute on her vision was the Equity and Empowerment Commission, which was created the previous year and tasked with doing racial equity and justice work in Evanston. She presented her ideas to the committee, and after receiving a warm reception, partnered with them to advance their goal of reparations. After spending much time collecting community feedback, working with City Council members and consulting local historians, a final proposal went up for vote in November of 2019, dubbed Resolution 126-R-19. The resolution was adopted by the city, and established a reparations committee, chaired by Rue Simmons, as well as an initial reparations fund of $10 million, collected from recreational cannabis sales tax, a product that was then recently legalized in Illinois.

Once the framework for establishing reparations in Evanston was laid, Rue Simmons’ work garnered attention from reparations leaders all across the globe, including Jackson Lee.

“Ever since 2019, [Lee and I] have worked in tandem, since the local movement is supporting the work of Congress in building more support for a federal bill for reparations,” said Rue Simmons.

Since their introduction to one another, Rue Simmons and Lee have spoken together on panels, at press conferences and at rallies in Washington D.C. Lee has visited Evanston multiple times, and often uses the city as an example of the feasibility of local reparations initiatives.

In Evanston, however, the distribution of the reparations fund was the subject of much debate. The first phase of reparations, based on months of community input, involved giving 16 residents $25,000, to be spent on housing-related payments only. A small but very vocal group of residents were upset that only $400,000 out of the $10 million was being distributed, and that it was part of a housing program, not a direct cash payment.

Add quote “This is not about your legacy…”

For Rue Simmons, that argument is unproductive when looking at reparations as a long term solution. While acknowledging that not everyone who deserves reparations can benefit from the housing program, she sees it as the first step in a long line of solutions.

“The argument [against the housing program] really was a false debate because there was never any intention that we only do a housing centered reparations initiative,” said Rue Simmons. “It was that we had to grow and build and get legal memos and the legal stamp of approval to get to cash [payments].”

Upon the announcement of the housing program, there were also some who claimed that the program was not even a form of reparations at all, a point that Rue Simmons vehemently disagrees with.

“When you acknowledge the harm to a specific injured community, apologize for that harm, commit to redressing it in the name of reparations, program it, fund it and disperse it to that community only, it is in fact reparations,” said Rue Simmons.

Other community leaders who have worked closely with Rue Simmons on the reparations initiative have expressed their support for the steps she’s taken, even if more complete reparations are in the future.

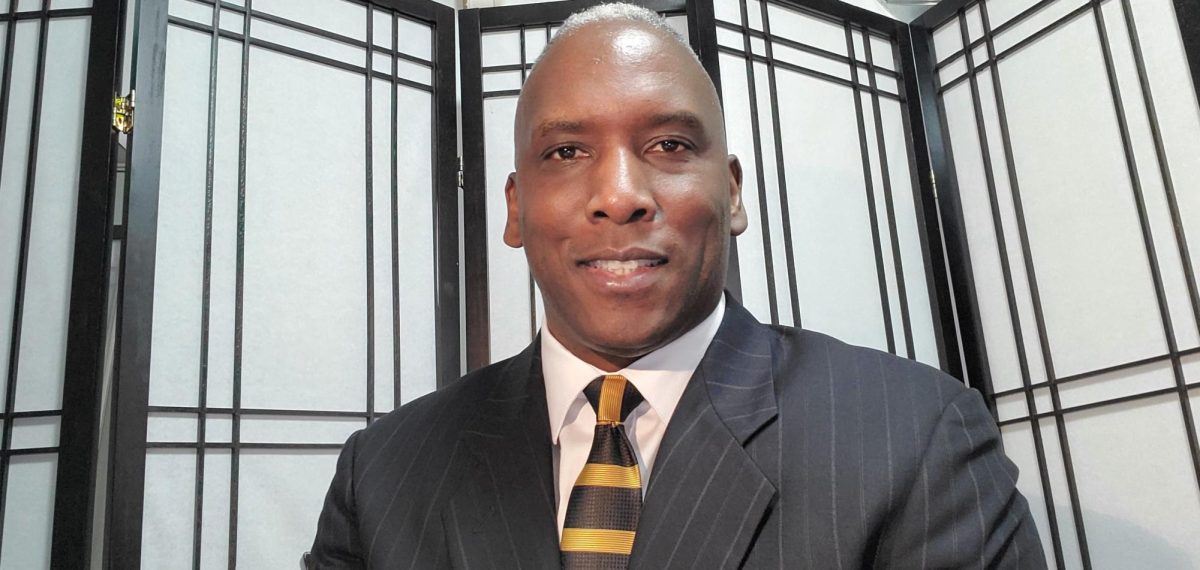

“Anybody can come to a table, look at someone else’s work and critique it,” said Dino Robinson, founder of the Shorefront Legacy Center, an organization dedicated to preserving Evanston’s Black history. “Even with a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, you can read into that book and critique it, saying ‘you misspelled that word’ or ‘the way you phrased that sentence is wrong.’ That’s easy to do. The hard work was writing the story in the first place.”

In 2021, Rue Simmons did not seek reelection as Fifth Ward alderwoman, instead focusing on her work as chair of Evanston’s Reparations Committee. She also founded and is the Executive Director of First Repair, a nonprofit organization that helps initiate local reparations movements in other cities across the U.S., from predominantly Black areas like Detroit, Mich. to predominantly white areas like Amherst, Mass.. Now, she leads a busy schedule, with more time spent traveling for work than in Evanston. Rue Simmons and her team at First Repair have been to the United Nations twice, have visited and supported the Caribbean movement for reparations in Jamaica and Rue Simmons has lectured at Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

When attempting to secure reparations in many different cities—and even countries—Rue Simmons partners with lawyers and legal professionals to determine the best course of action, as separate municipalities can have distinct legal structures.

“When it comes to legal framework or legal defense, I turn to our [legal reparations] leaders for that, and I do it swiftly so that they can respond appropriately and we can win reparations,” said Rue Simmons.

As more cities attempt reparations, and the City of Evanston moves into future stages of the fund distribution, the question of the true extent governments are willing to go for reparations arises, and what true reparations would even look like.

“The more that I’m engaged in this work and the more that I navigate life as a Black woman and mother of a Black man, I don’t know [what true reparations would look like],” said Rue Simmons.

However, she highlights that there are certain milestones to look for, including closing the wealth gap and achievement gap for Black students, addressing inequities in police treatment and closing the life expectancy gap between Black and white residents in the same town.

Since its initiation, the reparations fund in Evanston has grown to $20 million, with recent gains due to graduated real estate transfer taxes. Additionally, in 2023, the City Council approved direct cash payments as an option for distribution, addressing the concerns of those who weren’t in support of the housing program.

Rue Simmons continues to work with Jackson Lee to push for reparations at the federal level. Currently, bill HR-40 has passed out of the judiciary committee, but is waiting for complete approval by Congress.

As Rue Simmons continues her reparations work at the local, national and international level, she pushes forward with the same goal she’s had since childhood, to elevate the community that shaped her as a person.

“Reparations are very personal, yet it’s also a collective effort,” said Rue Simmons. “And ultimately, it looks like joy, safety, wellness and wealth for the Black community.”