Measuring up: the unique pressures on modern teen athletes

January 27, 2023

When asked what they wish adults knew about their experiences as high school athletes, students share common themes.

Junior Aidan Thomson’s busy swimming schedule overflows into the rest of his life.

“Understand how busy [we] are and how much pressure we’re under to do well in school as well as in sports,” says Thomson. “If somebody’s really exhausted every single day, that might just be because they have morning practice every single day and are really tired.”

Senior Claire Henthorn, a volleyball player, struggles to make room for every activity.

“You’re stressed because you have so much to do,” says Henthorn. “Sometimes you don’t have time.”

While playing badminton, junior Jillian Arnyai is conflicted between competition and enjoyment.

“I get so anxious every time I play because I just want to win,” says Arnyai. “You want to be happy because you’re playing a sport you love but at the same time, you’re just stressed out because you want to be your best.”

As junior tennis player Serik Hammond says, “sports, for athletes, that’s their life.”

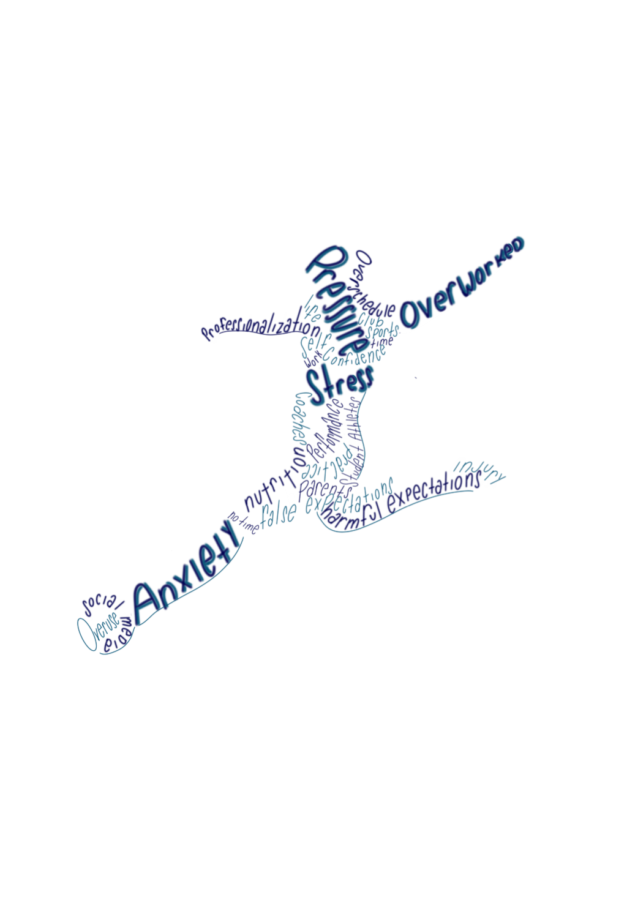

“Pressure.” “Stress.” “Anxiety.” Connectors between hundreds of students at ETHS– and millions throughout the country. The overwhelming aspect of daily sports is often a motivator for longer, more frequent practice and improvement over time. It can also be responsible for the deterioration of health. Sports become less about play and more about work: work to match a fitness threshold set by adults, who are at a different stage in mental and physical development.

The concept of overall fitness for high schoolers takes multiple definitions: the body ideals that one might see scrolling through social media, the gym schedules of hardworking peers or the advice of a well-meaning parent. In a nation where teenagers train year-round to match a standard of excellence in competitive sports, student-athletes face even greater pressure to match the fitness threshold of others.

While competition can be beneficial, it is easy for students to become overly critical of themselves or experience low self-confidence. As health impacts performance, performance in turn impacts health.

ETHS head athletic trainer Khaliah Elliston says, “I think a lot of people forget that mental health plays a role on these kids, and that affects them physically. Those two connect; you need both to have a good kid and a good athlete.”

Student-athletes constantly experience the stress of maintaining both personal perception of fitness and measuring up to the expectations of those around them. Since the foundation of competitive high-school sports, students have coped with these pressures. However, athletes in the 21st century face new challenges: namely, those of greater social media presence and increasing athletic standards.

Body image in the digital age

The idea of being “fit” in the modern-day relies on perception, and social media greatly shapes teenagers’ view of the world. Workout videos, or those titled “what I eat in a day,” are common on platforms frequented by high schoolers.

“I definitely see things pop up on how people who are athletes have a diet and how they exercise every day,” Henthorn says.

“I get so many posts recommended to me about workouts and nutrition and metabolic types,” agrees Arnyai. “It’s really hard when I see someone saying that you have to eat healthy to keep you healthy. They give diets that, if I tried, I could not live off of because I wouldn’t be getting all the nutrients I need.”

Even with an awareness of the impracticality of fitness influencers’ content, these messages can still impact an athlete’s mental state. As found in a study by the National Athletic Trainers’ Association, student-athletes are more likely to exhibit higher instances of decreased self-confidence and lack of appetite.

“In some sports, it is good to be tall, skinny,” says Arnyai. “But at least in my sport, it’s not a necessity. It’s just like, that’s what the media portrays as a healthy body and an athlete. It’s rough because that can get to you mentally which can affect how you play and then it’s a whole cycle.”

Healthy or athletic body types come in a wide range of shapes and sizes—especially among youth, who are still growing and developing and may not be able to maintain the definition seen in many fitness influencers. Pressure to conform to adult body standards increases when digital advice is focused on a specific sport.

“There’s a lot of false expectations that come out of social media that can majorly impact people’s body image,” agrees Thomson. “There’s a lot of stereotypes around swimmers.”

Not only are student-athletes facing pressure to conform to unrealistic standards through the media, packed schedules add another layer of stress to an athlete’s day. In-season practices are generally six days a week, for two hours every day.

“Sometimes you don’t even have time [to eat] because you have so much to do,” says Henthorn about her own experiences with nutrition. “Stress can be caused from body image and from playing a sport where you are competing against other people and thinking those negative thoughts of ‘I’m not good enough.’”

“When you’re in season, you’re playing seven days a week,” says Hammond. “Keeping a good balance between what you’re eating and how much you’re playing can affect everything.”

Nutrition is a highly specialized factor for athletes, where diet can impact performance, but also depends heavily on individual body composition. Generalized advice from figures through social media is often unproductive for a student.

Even with trusted adults, students receive greatly varying levels of engagement on diets and nutrition.

“I’ve gotten much more advice from parents than I have from my coaches about eating,” says Thomson. “My parents and other people’s parents really push eating what they think is healthy. We have team dinners and the parents decide that we’re all going to have pasta because that’s what we need.”

Hammond, like many others, has had the opposite experience, receiving little guidance from the closest people in his life. Discussing nutrition often can be helpful to form healthy habits and routines, especially as a teen and young adult. However, as body needs and composition are unique from person to person, it can be difficult to separate fact from fiction.

“My family doesn’t really talk about eating that much,” Hammond says. “I think it is important to find some place where you can find the truth and information. Probably not from social media, but whether it is from a family member or a friend or coach.”

Professionals who work closely with student-athletes can be the source of reliable information Hammond is looking for. Athletic trainer Elliston recommends reaching out to ETHS resources, such as nutrition services and trainers, with dietary concerns.

“Even if you don’t know how to specifically say it, just go and just have a conversation with [ETHS health professionals] about it. You have an abundance of resources here in this high school, even if you don’t even know the dietitian and you don’t know who the nurses are.”

High performance requires high commitment

High-performing athletes face another unique challenge: “sports professionalization,” where students are expected to meet an adult level of focus as teenagers. Especially when athletics can be an affordable gateway to college, pressure to compare to others can build up.

“At some point in time you have to specialize,” says Elliston. “When you’re thinking about going to college, where playing that sport pays for you to go to college. But at a young age, that’s not what you would want your child to do. They’re still growing.”

The high-school season is just one facet of sports for high-performers and those who wish to compete in college. Like many athletes, Henthorn feels pressure to compete in outside-of-school clubs before the season.

“I’d be stressed out on making the team for the school season,” Henthorn says. “I would think to myself that I need to stay playing volleyball so that I am ready for tryouts when they do come.”

Clubs and traveling teams can be even more competitive than school leagues and require greater commitment.

“We have two practices a day in my club season,” says Aidan Thomson. “Our coaches encourage us to go to all the practices. There is an expectation from your team and your other teammates who go to all the practices. There’s a decent amount of pressure.”

A 2018 study by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons noticed an increase in sports professionalization, especially among children: 54.7 percent of students were encouraged to specialize by their parents. With training and improvement beginning at increasingly younger ages, standards for performance rise.

“There’s always someone out there that’s better than you,” says Hammond. “You have all these kids who’ve been playing since they were five, six years old, so if you’re not playing 14 hours a week, you’re going to fall behind. It’s kind of on you to keep that up, which is a lot of pressure.”

While often necessary to measure up to peers, this year-round focus on one sport can be counterproductive for an athlete’s fitness. Overuse injuries from students overworking a specific muscle or motion are a common occurrence for athletic trainers.

“Of course, a basketball player, if he’s top of the line, is going to want to play basketball all year round,” Elliston says. “But using those same muscles every day, from age eight until [high school], those muscles wear out. Tendinitis becomes more prevalent, [and] cartilage wears out.”

In a separate study, conducted between 1997 and 2001 and published in the Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, female athletes engaging in sports specialization were given a significantly higher risk of injury. In general, total hours of vigorous physical activity were found to be directly related to chance of injury.

An athletic trainer’s advice? Variation is key.

“If you’re playing basketball, maybe switch it up and play baseball in the offseason,” says Elliston. “That way you’re using your shoulders in a different motion. You’re using different muscles. Maybe the muscles that are primary muscles during basketball season are accessory muscles during baseball season. It all makes a difference.”

Along with an effect on performance and health, packed schedules limit a student’s ability to spend time on schoolwork, or with friends, two things that are critical to a successful and happy high school experience.

“I have little to no time to hang out with other friends outside of swimming and it’s on top of schoolwork,” says Thomson. “If somebody’s really exhausted every single day, that might just be because they have morning practice every single day and they are just really tired.”

Imani Wilson, a social worker at ETHS for the class of 2023, explains, “Overscheduling can be really detrimental to one’s mental health. I tell my students that it’s important to have ‘white space’ on your calendar, meaning, completely unscheduled time. We need this time to reflect on the things we’re involved in and ask ourselves whether these things are really important to us. We also need this time to just do nothing.”

Unfortunately for a lot of student-athletes, this “white space” is often impossible or rare while in season.

“When it comes to balancing school and sports, I think the most important thing is to try to keep yourself organized, and to establish some routines,” says Wilson. “As a student-athlete, waiting until the last minute to get started on an assignment likely won’t go over well due to having already limited availability.”

Balance is possible. ETHS prides itself on its both academically and behaviorally exceptional students. Among eligibility and sportsmanship requirements, all student-athletes have the potential to represent the best and the brightest of Evanston. Many credit sports teams as a source of stability and support.

“I think sports can have an incredibly positive effect on a student’s mental health,” writes Imani Wilson. “Sports offer community, social support, physical activity, and an opportunity to work towards mastery on something…all things that are crucial to our mental health.”

With the right mentality–and the right advice–this community can be a highlight of high school and a building block for the rest of life. Genuine enjoyment, and not pressure from outside sources, is the best motivation towards participation in athletics.

“Take your freshman and sophomore year as a young adolescent to find what your niche is,” says Khaliah Elliston. “But also find what gives you an emotional release.”